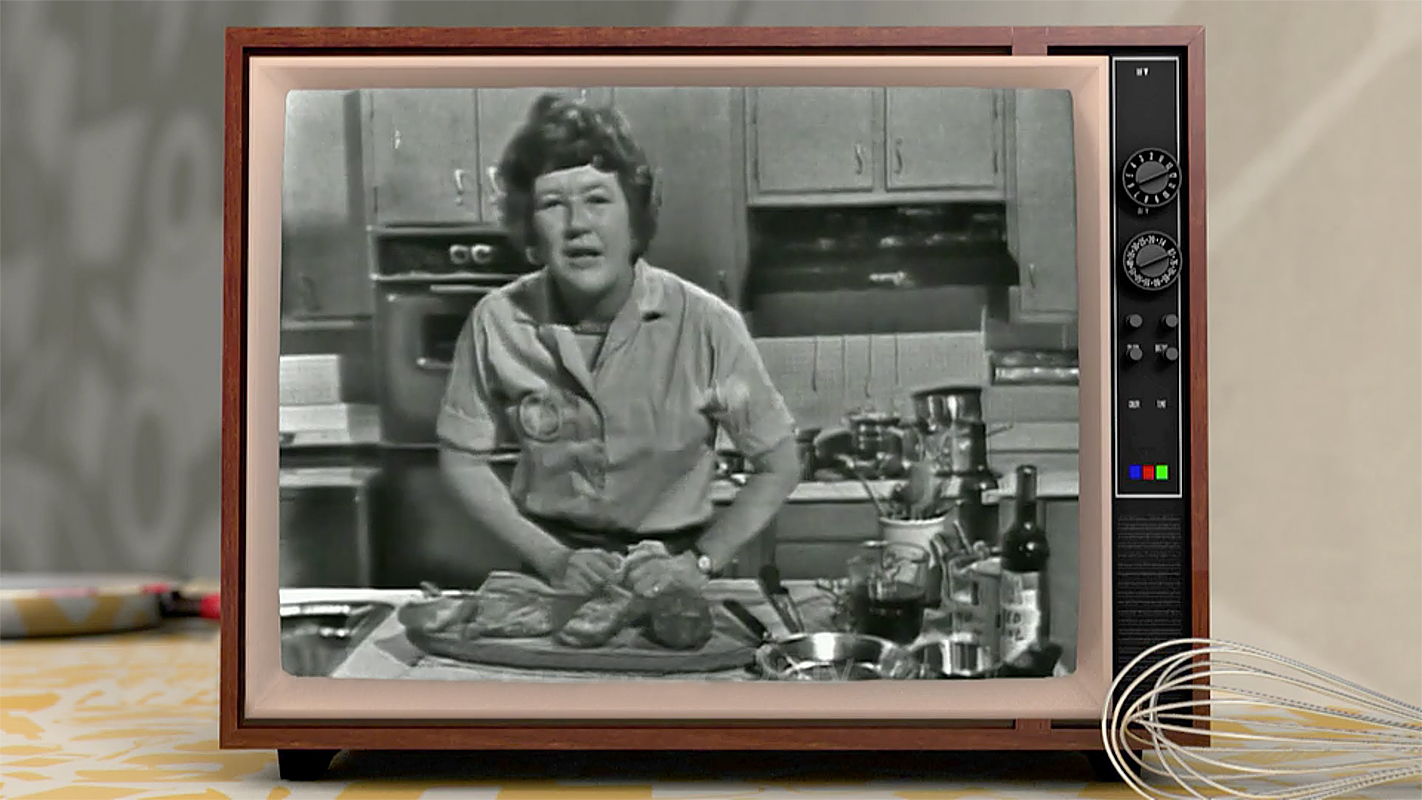

It is a Tuesday in 1963. A tall, exuberant woman with a voice like a friendly foghorn is standing in a studio kitchen. She is waving a piece of raw beef. This was the moment Americans met Julia Child boeuf bourguignon.

Before this, French food was for fancy people in tuxedos. It was scary. It was "haute cuisine." Then Julia showed up and basically told the world that a messy beef stew was the pinnacle of human achievement. Honestly, she wasn't wrong.

But here is the thing: most people today make it wrong. They treat it like a Crock-Pot recipe where you just "set it and forget it." If you do that, you aren't making Julia’s version. You're just making damp beef. Her recipe is a multi-hour labor of love that involves enough pots and pans to fill a small dishwasher twice over. It is a process. It is a ritual.

Why You Must Dry Your Meat (The Science of the Sear)

Most home cooks skip the most important sentence in Mastering the Art of French Cooking. It is on page 315. "Dry the beef in paper towels; it will not brown if it is damp."

Two words. Damp beef.

✨ Don't miss: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

If your meat is wet when it hits the oil, the water turns to steam. Steam is the enemy of the Maillard reaction. You want that deep, dark, caramelized crust. Without it, the sauce lacks depth. You've basically boiled the meat in its own juices before the wine even touches the pan.

Julia was obsessive about this. She’d have you standing there with a roll of paper towels, patting 3 pounds of chuck roast like you’re drying a newborn baby. It feels tedious. You’ll think, "Does this really matter?" Yes. It does.

The Bacon Secret Nobody Mentions

Ever wonder why she tells you to simmer the bacon in water first? Most Americans think bacon is for flavor, and they want it smoky. Julia wanted the fat, but she hated the "cheap" smoke flavor of 1960s supermarket bacon.

By simmering the lardons (those little sticks of bacon) in water for 10 minutes, you remove the excess salt and that overpowering smoky tang. This leaves you with clean, rendered pork fat to sear the beef. It’s a subtle shift. It makes the final dish taste like a French countryside, not a Saturday morning breakfast diner.

🔗 Read more: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The Wine: Don't Buy "Cooking Wine"

If you use that salty "cooking wine" from the grocery store aisle, you’ve already lost. Please don't. Julia specifically recommended a full-bodied, young red. A Burgundy is traditional, obviously, but a good Beaujolais, Cotes du Rhone, or even a Chianti works.

The wine is the soul of the dish. It shouldn’t be something you wouldn't drink. As the sauce reduces, those flavors concentrate. If the wine is bitter or overly acidic, your Julia Child boeuf bourguignon will be too.

The Three-Pot Nightmare (That Is Worth It)

One of the biggest misconceptions is that this is a one-pot meal. It isn’t. Not if you’re doing it the "Julia way."

- Pot 1: The Dutch oven where the beef and wine braise.

- Pot 2: The skillet for the "Oignons Glacés à Brun" (brown-braised onions).

- Pot 3: The pan for the mushrooms sautéed in butter.

Why the separation? Because if you throw the mushrooms and onions in at the beginning, they turn into gray mush. They lose their identity. Julia insisted on cooking the pearl onions separately in beef stock and butter until they were tender but still held their shape.

💡 You might also like: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The mushrooms get their own high-heat sauté. You want them golden. You want them to "squeak" when you bite into them. You only fold them into the stew at the very end. This creates a texture profile that most modern stews completely lack.

Mastering the Sauce Consistency

When the meat is done—usually after 2.5 to 3 hours at a low $325^\circ F$ (160°C) simmer—the work isn't over. Julia has you pour the entire contents of the pot through a sieve.

You skim the fat off the liquid. Then you simmer that liquid on the stove. You're looking for a sauce that "coats a spoon lightly." If it’s too thin, you boil it down. If it’s too thick, you add a spoonful of stock.

This is the "velvet" stage. Most people serve a watery broth. Julia wanted a sauce that hugged the meat.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Overcrowding the pan: If you put all the beef in at once, the temperature drops. The meat won't sear. Brown it in batches.

- Using the wrong cut: You need beef chuck roast. It has the connective tissue (collagen) that melts into gelatin. Leaner cuts like sirloin will turn into shoe leather after three hours in the oven.

- Rushing the braise: If the meat isn't fork-tender, it needs more time. Don't pull it out just because the timer went off.

- Skipping the rest: This dish is actually better the next day. The flavors settle. The beef reabsorbs the sauce. If you can wait, make it on Saturday to eat on Sunday.

Taking Action: Your Game Plan

If you're ready to tackle this, don't just wing it. It's a project.

- Prep everything first. This is mise en place. Peel the pearl onions and quarter the mushrooms before you ever turn on the stove.

- Get the right equipment. You need a heavy-bottomed Dutch oven. Enameled cast iron is the gold standard here because it holds a steady, gentle heat.

- Check your temperature. Your oven should be low. The liquid should barely "smile"—just a few bubbles breaking the surface. A violent boil will toughen the meat fibers.

- Serve it right. Boiled potatoes are the classic accompaniment. They soak up that velvet sauce better than anything else.

This isn't just a recipe. It's a piece of history that changed how a whole generation thought about their kitchens. It takes all afternoon, your kitchen will be a disaster, and you'll be exhausted. But when you take that first bite of beef that collapses under a fork, you’ll realize why we are still talking about this dish sixty years later.