If you pull up a digital map and look for the Jordan River, you'll see a blue line snaking down from the base of Mount Hermon, through the Sea of Galilee, and ending at the Dead Sea. On a screen, it looks like a robust, definitive border. But honestly? If you actually stood on its banks today in 2026, you might be shocked by what’s actually there.

It is much smaller than the Sunday school stories or the epic maps suggest.

The Jordan River on map views often hides a messy, complicated reality of modern engineering, political tension, and a desperate struggle for water. It’s not just a river; it’s a plumbing system for three different countries. What used to be a rushing torrent that could flood its valley is now, in many stretches, a narrow, salty stream that you could almost jump across.

Where the Jordan River actually goes

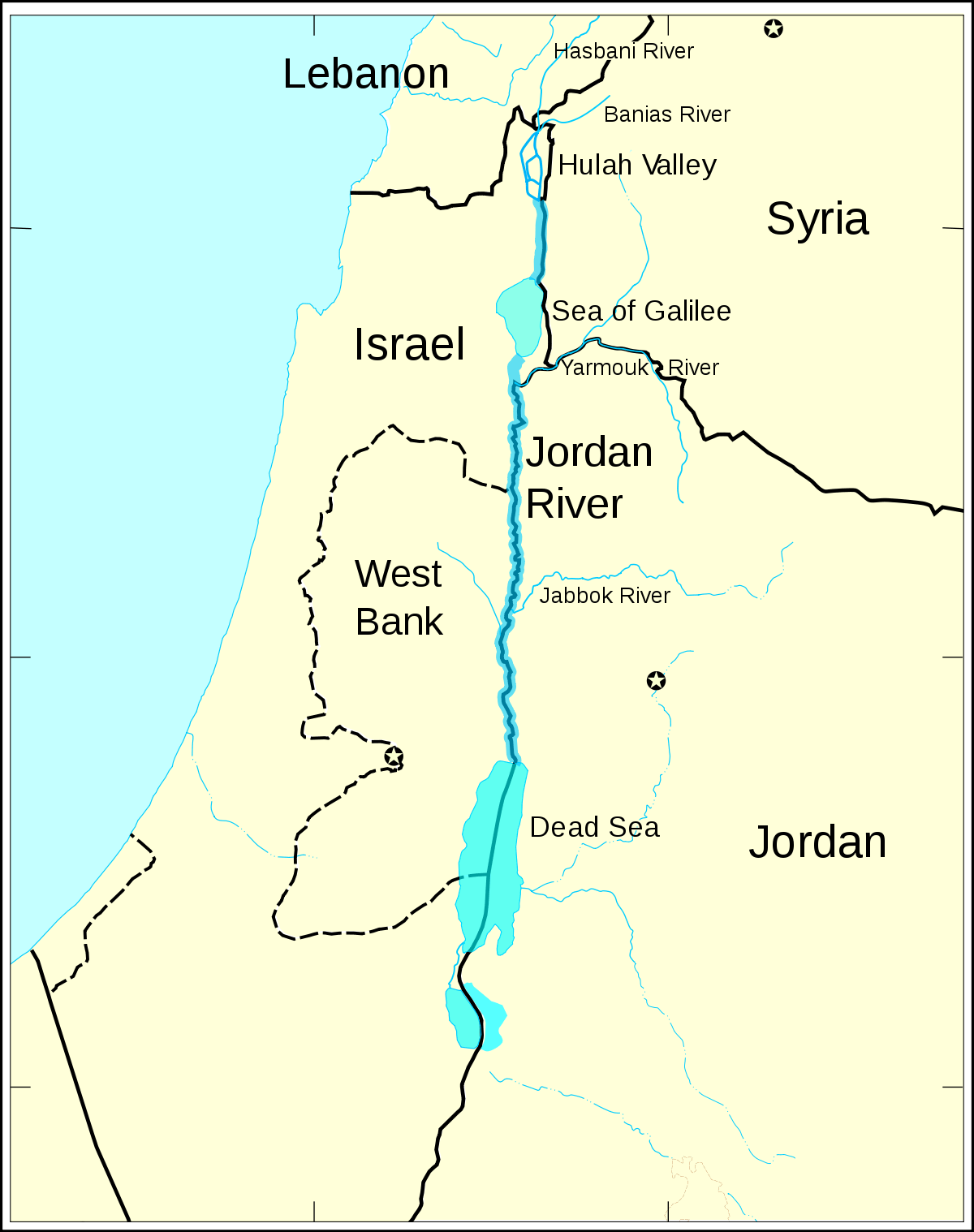

To find the jordan river on map, you have to start way up north. The river begins where three main springs—the Hasbani in Lebanon, the Banias in Syria, and the Dan in Israel—converge in the Hula Valley. From there, it rushes down a steep basalt gorge into the Sea of Galilee.

This northern section is the "Upper Jordan." It’s actually quite beautiful and relatively clean. Tourists love to raft here. But once the water hits the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret), everything changes.

South of the lake is the "Lower Jordan." This is the part that usually serves as the international border between Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank to the west. On your GPS, this looks like a continuous flow. In reality, the Degania Dam at the southern tip of the Sea of Galilee controls almost every drop. Most of the fresh water is diverted into the National Water Carrier to keep taps running in Tel Aviv or Amman.

What’s left to flow south? Basically, it’s a mix of agricultural runoff, some treated sewage, and saline springs. It’s a harsh reality that surprises people who expect a pristine biblical waterway.

The disappearing act of the Dead Sea

If you follow the jordan river on map all the way to its terminus, you hit the Dead Sea. Except, "hitting" the Dead Sea is getting harder every year.

🔗 Read more: Hava durumu New York: Neden Beklediğinizden Çok Daha Karmaşık?

Because the river’s flow has been reduced by about 90% compared to a century ago, the Dead Sea is literally starving. It’s dropping by more than a meter every year. If you look at satellite imagery from the 1970s versus today, the transformation is haunting. The southern basin is now almost entirely artificial evaporation ponds used for mineral extraction.

The river doesn't just "end" anymore; it peters out into a delta of mud and sinkholes.

Why the map is a bit of a lie

Maps are static. The Jordan River is anything but.

- The Meander Factor: The river is incredibly "loopy." While the straight-line distance from the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea is only about 65 miles, the river actually twists and turns for over 135 miles.

- The Zhor vs. The Ghor: Geographers talk about the "Zhor," which is the narrow, lush flood plain where the river actually sits, and the "Ghor," the wider, higher plateau of the Jordan Valley. If you're looking at a physical map, the green strip you see is the Zhor, but it's much narrower than it used to be.

- The Tributaries: The Yarmouk River is the biggest tributary, coming in from the east (Syria/Jordan). It used to provide a huge boost to the Jordan, but today, it’s heavily dammed before it ever reaches the main stem.

Politics and the 2026 Water Reality

Living in this region means water is more valuable than gold. Jordan is currently one of the most water-stressed nations on the planet. When you see the jordan river on map acting as a border, you’re seeing a line that both sides are trying to manage without causing a diplomatic crisis.

There’s been talk for years about the "Red-Dead" project—pumping water from the Red Sea to save the Dead Sea—but geopolitical shifts have made that a roller coaster of "maybe" and "no." Recently, focus has shifted toward massive desalination plants on the Mediterranean coast. The idea is to swap desalinated water for solar energy. It's a "water-for-energy" deal that makes a lot of sense on paper, but in the Middle East, nothing is ever simple.

How to actually see it

If you're traveling and want to find the jordan river on map in person, you can’t just pull over anywhere. Much of the riverbank is a closed military zone because it is an international border.

The most popular spots are:

- Yardenit: Near the Sea of Galilee. It’s very green and set up for baptisms. This is the "clean" part.

- Qasr el Yahud: Located near Jericho. This is the traditional site where Jesus was said to be baptized. It’s a surreal experience—you’re standing on one wooden dock in the West Bank, and just ten feet away across a brown, narrow stream, people are standing on a dock in the Kingdom of Jordan.

- The Peace Island: Located at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers. It’s a bit of a relic of the 1994 peace treaty, though access has been restricted in recent years.

Practical Steps for Map Nerds and Travelers

If you are planning to explore the Jordan River valley or are just studying the geography, don't rely on a basic road map. Use high-resolution satellite layers like those found in Google Earth or Sentinel-2 imagery to see the actual water levels.

For those on the ground, always check local military permits if you're trying to hike the valley. The border is heavily monitored. If you want to support the river's health, look into the work of EcoPeace Middle East. They are a unique organization made up of Jordanians, Palestinians, and Israelis working together to restore the river's flow.

To get the most accurate view of the jordan river on map today, look for "topographic" layers that show the extreme elevation drops. Remember, you are looking at the lowest river on Earth, ending at the lowest point on dry land. That kind of geography creates a microclimate that is scorching in the summer but surprisingly pleasant in the winter, making it a perfect spot for off-the-beaten-path exploration during the cooler months.

Check the "Sea of Galilee" water levels (the "Red Line") before you go. If it’s been a rainy winter, the dams might be opened slightly, giving the Lower Jordan a rare, brief taste of what it used to be: a living, breathing river.