You’ve seen it in Sunday school sketches or on a flickering screen during a news broadcast. On a standard world atlas, the Jordan River looks like a tiny, squiggly vein connecting the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea. It’s the ultimate geographic celebrity. But honestly, if you actually went there today with a paper map in hand, you might feel a little cheated.

The jordan river on a map looks like a robust border. In reality, large stretches of the lower river have slowed to a salty, polluted trickle that you could practically hop across in some spots.

It's a weird piece of geography. For one thing, it flows through the lowest structural depression on the planet. We’re talking about the Great Rift Valley, a massive crack in the Earth’s crust that runs all the way from Turkey down into Africa. Because of this, the river doesn't just flow "south"—it drops. It plunges from about 9,200 feet at the snowy peaks of Mount Hermon to nearly 1,412 feet below sea level at the Dead Sea.

Where the Jordan River Starts and Ends

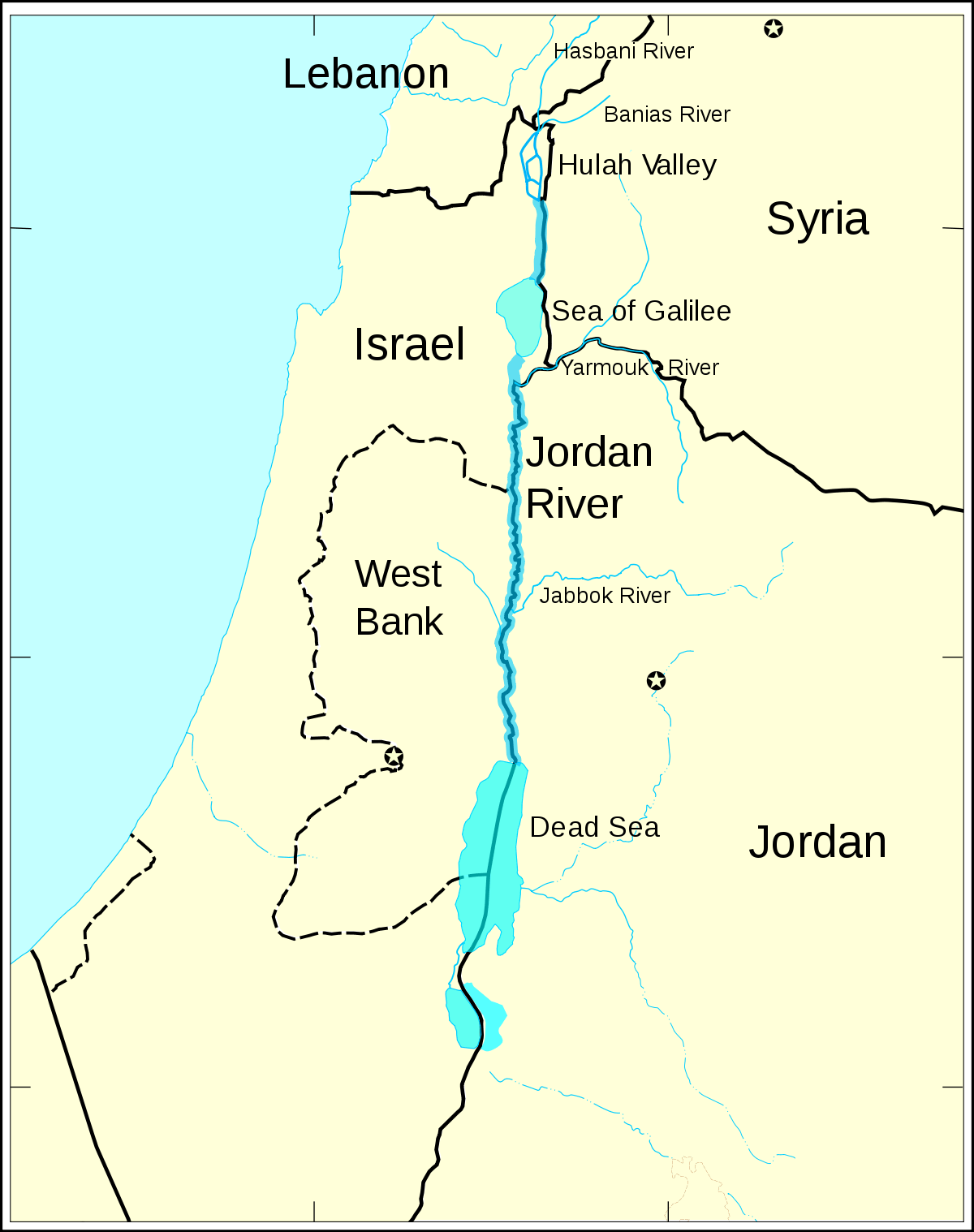

Tracing the jordan river on a map requires looking way up north to the "triple point" where Israel, Lebanon, and Syria sort of collide. It doesn't start as one river. It’s more like a three-headed hydra:

- The Hasbani (coming out of Lebanon).

- The Banias (surfacing in Syria).

- The Dan (the biggest one, bubbling up in Israel).

These three streams merge in the Hula Valley. Back in the day, this area was a giant swampy lake, but humans drained it in the 1950s for farmland—a move that local ecologists are still debating today. From there, the water rushes into the Sea of Galilee (also known as Lake Tiberias).

💡 You might also like: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

Once it leaves the southern tip of the Galilee at the Degania Dam, things get complicated. This is the "Lower Jordan River," and it’s the part that serves as the international border between the country of Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank to the west.

The Disappearing Act: Why the Map Lies

If you look at a map from 1920, the Jordan River was a wild, meandering beast. It carried roughly 1.3 billion cubic meters of water every year to the Dead Sea.

Today? You’re looking at maybe 70 to 100 million cubic meters.

Basically, 95% of the river’s original flow is diverted before it ever reaches the southern valley. Israel, Jordan, and Syria all tap into the tributaries for drinking water and irrigation. What’s left in the channel is mostly a mix of agricultural runoff, treated (and sometimes untreated) sewage, and salty springs. It’s a bit of a tragedy, really. The Dead Sea is shrinking by about three feet every year because its main "faucet"—the Jordan—is almost turned off.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Lake Placid Town Map Doesn’t Tell You

A Quick Comparison: Then vs. Now

| Feature | Historical Jordan | Modern Jordan (2026) |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Flow | 1.3 Billion Cubic Meters | <100 Million Cubic Meters |

| Water Quality | Fresh, potable | Highly saline/polluted in lower sections |

| Primary Use | Natural ecosystem | Irrigation & Political border |

| Width | Deep, wide meanders | A narrow stream in many parts |

Mapping the Political Tension

Mapping this river isn't just about geology; it's about politics. For about 75 miles, the river is a literal fence. If you're standing on the west bank, you’re in the West Bank or Israel. If you look across the reeds, you’re looking at the Kingdom of Jordan.

Military outposts line both sides. It’s one of the most heavily monitored borders in the world.

There's also the "Yarmouk River" factor. This is the Jordan's biggest tributary, coming in from the east. It forms the border between Syria and Jordan before it hits the main river. If you find the spot on the map where the Yarmouk hits the Jordan, you’ve found the "tri-point" of Israel, Jordan, and Syria. It’s a geopolitical hotspot where water rights are more valuable than gold.

What Most People Get Wrong

One big misconception is that the Jordan is a "mighty" river like the Nile or the Mississippi. It's not. Even at its peak, it was never a massive waterway for ships. It's narrow—usually only 50 to 75 feet wide.

👉 See also: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

Another surprise? It doesn't flow into the ocean. It’s an "endorheic" river, which is a fancy way of saying it flows into a closed basin. It ends at the Dead Sea, where the water has nowhere else to go but up (evaporation), leaving behind all those famous salts and minerals.

How to Actually See It

If you want to see the jordan river on a map in real life, you have a few options that feel very different from each other:

- The Northern End (Tel Dan): Go here if you want to see the river looking like a lush, cold, European mountain stream. It’s green, fast, and beautiful.

- Yardenit: Just south of the Sea of Galilee. This is where the tourists go. It’s clean, calm, and there are facilities for baptisms.

- Qasr el-Yahud: This is the site near Jericho where many believe Jesus was baptized. Here, the river is narrow and brownish, and you can see Jordanian soldiers just a few yards away on the other bank.

Actionable Insights for Your Map Search

If you're trying to use a map to plan a trip or do research, here’s how to get the best results:

- Use Satellite View: Standard "map" views often make the river look like a thick blue line. Switch to satellite mode on Google Maps to see the actual "Zor"—the narrow, green jungle strip that grows along the riverbed in the middle of the desert.

- Check Flow Status: If you're visiting for kayaking, check local reports. In the summer, the lower sections can get quite stagnant.

- Look for the "Peace Island": This is a specific spot (Naharayim) where the Yarmouk and Jordan meet. It’s a unique historical site that shows how the river has been used for both cooperation and conflict.

The jordan river on a map tells a story of a landscape under pressure. It's a miracle it's still there at all, considering how many people are thirsty for its water. To see it properly, you have to look past the blue line and see the history, the politics, and the dry rocks that define the Levant today.

Start by looking at the Hula Valley on a 3D terrain map to see how the water is funneled down through the mountains—it gives you a much better sense of why this tiny river has been the center of world history for thousands of years.