You’ve probably seen the paintings. Majestic, wide, blue waters with palm trees leaning over the banks. If you go to the Middle East expecting that, you’re honestly going to be a bit confused. The Jordan River is, in many places today, barely more than a muddy creek you could almost jump across.

It’s small. It’s murky. It’s also the most famous river on the planet.

How does a 156-mile-long stream that ends in a salt lake manage to be the center of three world religions and a modern geopolitical flashpoint? Basically, it’s not about the size of the water; it’s about the stories and the soil.

Where Exactly Is the Jordan River?

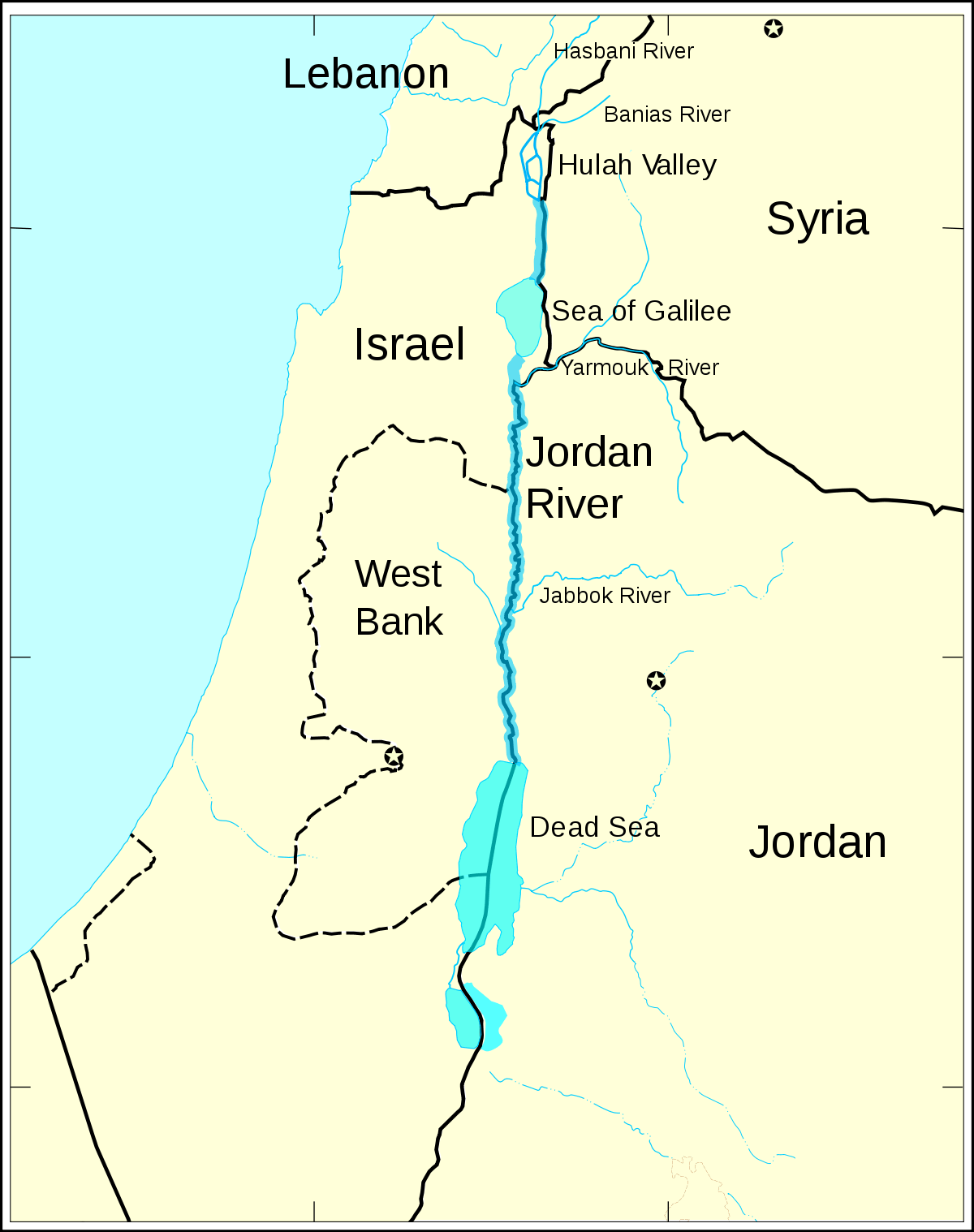

Geography class time, but I’ll keep it quick. The Jordan River starts way up north at the base of Mount Hermon, right where the borders of Lebanon, Syria, and Israel meet. It’s fed by melting snow and springs, creating this surprisingly lush, green pocket in an otherwise dusty landscape.

📖 Related: Paso Robles Inn Spring Street Paso Robles CA: Why Locals Still Love This Spot

From there, it flows south.

It hits the Sea of Galilee—which is actually a freshwater lake—stays for a bit, and then exits out the southern end. This is where things get interesting. As it heads toward its final destination, the Dead Sea, it forms the boundary between the country of Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank to the west.

By the time it reaches the Dead Sea, it’s at the lowest point on the surface of the Earth. We’re talking roughly 1,400 feet below sea level.

It’s literally "The Descender"

The name "Jordan" comes from the Hebrew word Yarden, which means "to descend" or "go down." It makes sense. The river drops thousands of feet in elevation from its mountain headwaters to its salty grave.

The Spiritual Heavyweight Champion

If you ask a traveler or a pilgrim, "What is Jordan River to you?" you’ll get three different answers depending on who they are.

For Christians, this is the site of the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist. It’s the "source" of all holy water. Even today, despite the water quality issues, you’ll see thousands of people in white robes dunking themselves at sites like Yardenit or Qasr el-Yahud. They aren't looking for a swim; they’re looking for a connection to something 2,000 years old.

Jewish history puts the river at the center of the "Promised Land" story. After forty years in the desert, the Israelites crossed the Jordan to enter Jericho. It wasn't just a crossing; it was a transition from wandering to home.

In Islam, the river valley is a site of deep respect. Many of the Prophet Muhammad’s companions are buried along its eastern bank. It’s viewed as a place where miracles happened and where the landscape itself reflects the bounty of the divine.

The Reality Check: It’s Shrinking

Now, here is the part that’s kinda sad. If you look at photos from a century ago, the Jordan was a wild, flooding beast. It could be a mile wide in the winter.

Not anymore.

Today, about 90% of its natural flow is diverted. Israel, Jordan, and Syria all need that water for drinking and farming. When you take that much water out of the top and middle, what’s left at the bottom? Honestly, not much. The lower Jordan is mostly a mix of treated (and sometimes untreated) sewage and agricultural runoff.

- The Sea of Galilee is often dammed at the south to keep water in the lake.

- The Yarmouk River, its biggest tributary, is heavily diverted by Syria and Jordan.

- Evaporation in the scorching heat takes a massive toll.

Environmental groups like EcoPeace Middle East have been screaming about this for years. As of early 2026, there are some small wins—new deals between Israel and Jordan to swap desalinated water for solar energy—but the river still struggles to reach the Dead Sea. Because the Jordan is "dying," the Dead Sea is shrinking too, dropping about a meter every single year.

✨ Don't miss: Map of the Middle America: Why Our Mental Borders Are Almost Always Wrong

Visiting the River Today

If you’re planning a trip, don't just show up at a random spot on the map. Most of the river is a closed military zone because it serves as an international border.

You’ll want to head to the official sites. Yardenit is near the Sea of Galilee and feels a bit like a lush park. It’s clean, organized, and very "tourist-friendly." If you want something that feels more rugged and historical, Qasr el-Yahud (near Jericho) is where many scholars believe the actual biblical events took place. Just be prepared: the water there is brown. That’s not necessarily dirt; it’s silt and sediment from the riverbed, but it’s a far cry from a Caribbean beach.

Why It Still Matters

So, what is the Jordan River? It’s a paradox. It’s a tiny stream with a massive ego. It’s a border that separates people and a resource that forces them to talk to each other.

In a world where we’re increasingly worried about climate change and water scarcity, the Jordan is the "canary in the coal mine." If the people in this region can figure out how to share and save this one little river, there’s hope for everyone else.

📖 Related: 10 days paris weather: What Most People Get Wrong

Next Steps for Your Trip or Research:

- Check the water quality alerts: If you plan on a ritual baptism, check local 2026 health advisories, as bacterial counts can spike after heavy rains.

- Visit the Jordan Side: Most people see the river from Israel, but the "Bethany Beyond the Jordan" site in the Kingdom of Jordan offers a much quieter, more contemplative experience.

- Support Restoration: Look into the "Jordan River Master Plan"—a transboundary effort to bring fresh water back to the valley by 2030.

The river might be a trickle, but its story is still a flood.

Actionable Insight: If you are visiting for religious reasons, aim for the spring months (March-May). The weather is manageable, and the water levels are at their highest before the summer heat begins to evaporate the flow. If you're a history buff, focus on the "Three Bridges" area where Roman, Ottoman, and British ruins still stand side-by-side.