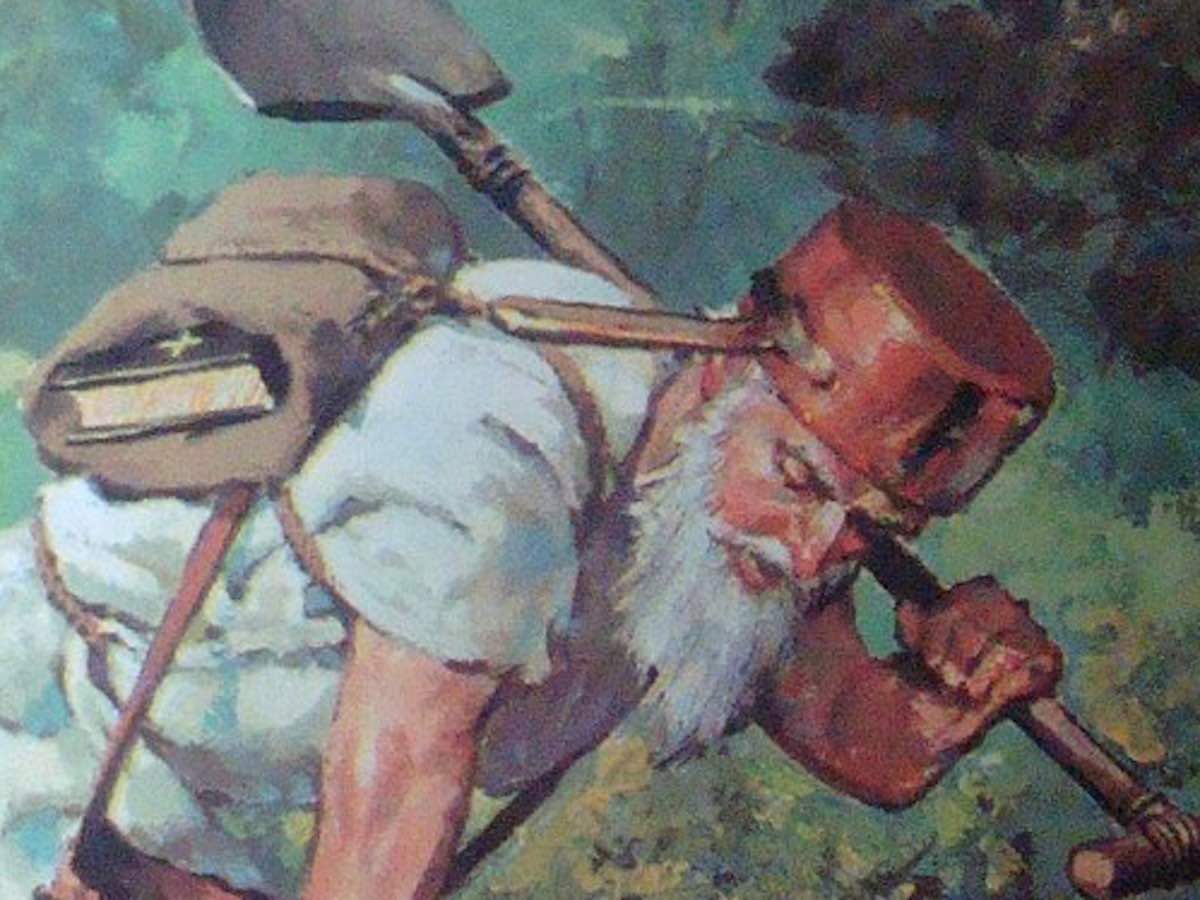

You’ve seen the cartoon. A guy with a tin pot on his head, barefoot, wandering through the woods while tossing apple seeds into the wind like some kind of woodland fairy. It’s a cute story.

Honestly, it’s also mostly garbage.

The real Johnny Appleseed, born John Chapman in 1774, wasn't a random drifter. He was a shrewd businessman, a missionary for a fringe Swedish religion, and a land speculator who owned over 1,200 acres by the time he died. He didn’t just "toss" seeds. He planted sophisticated nurseries, fenced them in to keep the deer out, and sold the trees to settlers. Oh, and those apples? You couldn't eat them. If you bit into one, you’d probably spit it out immediately because they were "spitters"—bitter, sour little things only good for one thing: hard cider.

The Business of Being Johnny Appleseed

John Chapman was basically the 19th-century version of a real estate developer.

In the early 1800s, frontier law in places like Ohio and Indiana was pretty specific. To claim land, you often had to prove you were "improving" it. One of the easiest ways to show improvement? Planting an orchard. By the time the settlers arrived, Chapman already had seedling trees ready to sell. He was stayin' one step ahead of the migration, setting up shops (nurseries) in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana.

He wasn't just doing this for the vibes. It was a business model.

🔗 Read more: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Records from the time show he was meticulous. He’d gather his seeds from cider mills in Pennsylvania—literally picking through the leftover pulp—and then haul them by canoe or on his back into the wilderness. He wasn't giving them all away for free, though he was known to be generous if a family was broke. Most of the time, he traded for clothes, food, or small amounts of cash.

Why he didn't use grafting

If you buy a Honeycrisp apple today, that tree was made through grafting. That's a process where you take a piece of a "good" tree and fuse it onto a root. It’s how you get consistent fruit. John Chapman hated this.

He was a devout follower of Emanuel Swedenborg, a mystic who founded the New Church. Chapman believed that grafting was a form of "mutilation" and that plants should be allowed to grow from seed as God intended.

Because he refused to graft, every single tree he planted was a genetic lottery. And in the world of apples, the lottery usually results in "crab" apples. They were small, hard, and tart.

But for a pioneer in 1810, this was perfect.

💡 You might also like: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Water on the frontier was often contaminated and could kill you with cholera or typhoid. Hard cider was the safe alternative. It was the daily beverage for men, women, and even children. Chapman wasn't just a "nurseryman"; he was the man providing the raw materials for the frontier’s favorite booze.

The barefoot mystic in a coffee sack

The legend of his clothes is actually mostly true.

He really did wear a coffee sack with holes cut out for his arms. He really did go barefoot, even in the snow, which sounds absolutely miserable. One story claims he had feet so calloused that he could put a hot coal on them without feeling it. He did carry a tin pot, though historians debate if he actually wore it as a hat or just used it for cooking and carried it that way to save space.

His religion dictated his life. He was a vegetarian before that was even a word in the common American vocabulary. He was so dedicated to non-violence that he reportedly felt guilty after accidentally killing a mosquito. There’s even a story about him putting out a campfire because he noticed some bugs were flying into the flames.

People thought he was weird. Obviously. But they also respected him.

📖 Related: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

He was one of the few white men who could travel safely between settler cabins and Native American villages. He respected the indigenous tribes, learned their languages, and often acted as a messenger or a warning system when tensions flared up. He was a bridge between two worlds that were often at war.

Where did the real John Chapman go?

He died in 1845.

It wasn't a peaceful death in a bed of flowers. He was 70 years old, which was ancient for that era, and he had spent his final days trying to repair a fence at one of his nurseries near Fort Wayne, Indiana. He caught pneumonia—likely "the winter plague" as they called it—and died at a friend's house.

If you go to Fort Wayne today, you can visit his grave in Johnny Appleseed Park. Or at least, where they think he’s buried. There was a huge debate for years about the exact spot, because he was buried in a family plot that eventually got moved and shifted over time.

What can we learn from the real Johnny Appleseed?

It’s easy to dismiss the story as a kids' fable, but the reality of John Chapman is much more interesting for anyone looking to understand the American frontier.

- Entrepreneurship requires foresight: He didn't wait for the customers to arrive; he built the infrastructure they’d need before they even knew they needed it.

- Sustainability isn't new: He was a "conservationist" before the term existed, protecting the genetic diversity of apples and living a life of minimal waste.

- Your reputation is your currency: In a lawless wilderness, Chapman’s "brand" as a kind, honest, and slightly eccentric man allowed him to travel thousands of miles without being harmed.

If you're ever in the Midwest and see an old, gnarled apple tree in the middle of a forest, there’s a non-zero chance a piece of its DNA started in a coffee sack carried by a guy with no shoes.

To dig deeper into the actual history of the frontier, you should check out the archives at the Heinz History Center or look into the writings of Michael Pollan, who did a fantastic breakdown of Chapman’s "cider-centric" business model in The Botany of Desire. Understanding the real man makes the legend feel a lot less like a cartoon and a lot more like a weird, gritty, and impressive piece of history.