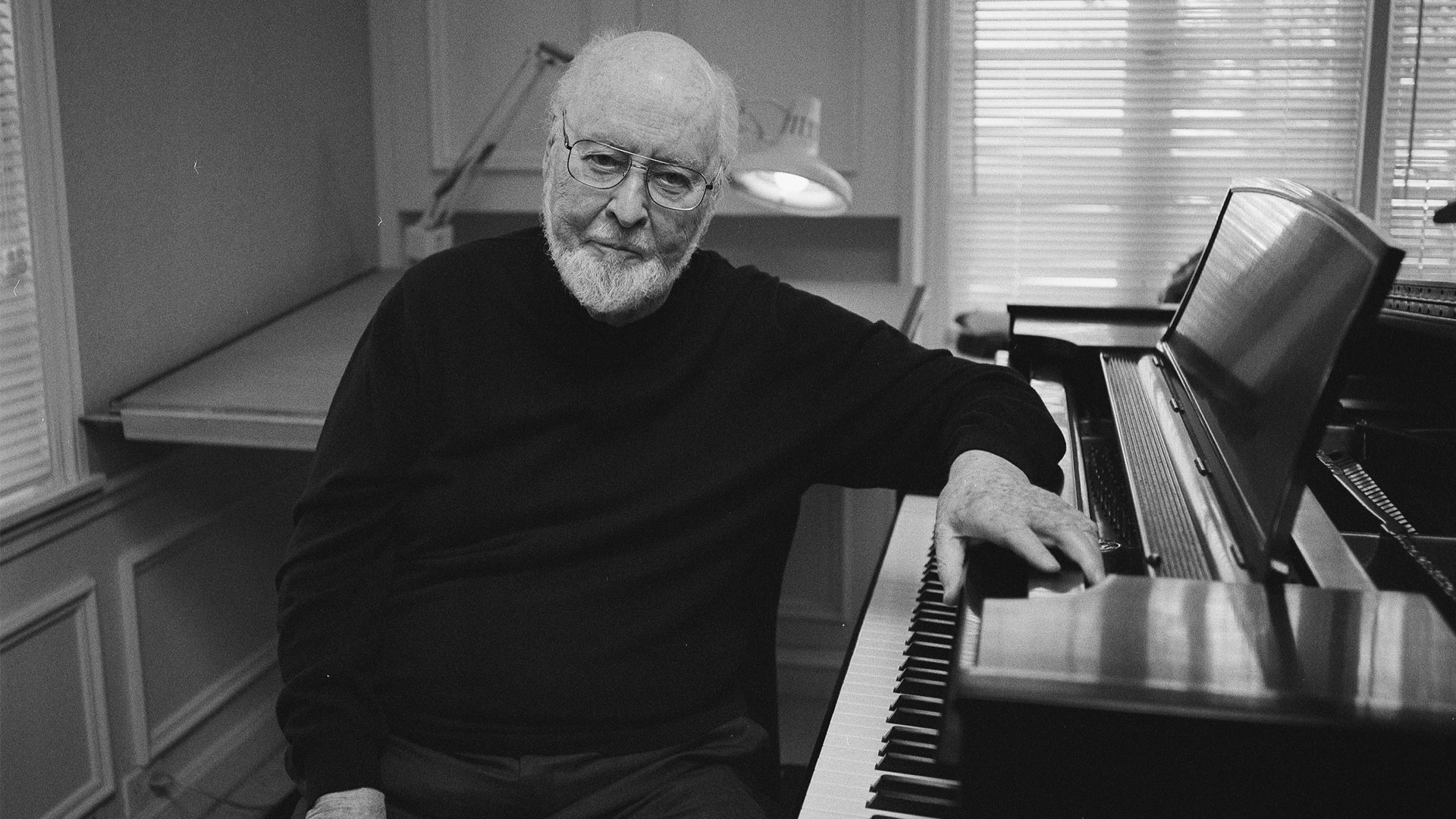

You know that feeling when you're sitting in a dark theater, the lights dim, and that first massive blast of brass hits your chest? That's not just sound. It’s John Williams. Honestly, it’s hard to imagine what our collective movie-going memories would even look like—or sound like—without him.

Think about it. If you strip away the music from Jaws, you basically just have a mechanical shark that wouldn't stop breaking down on set and a bunch of guys on a boat looking stressed. But add those two simple, terrifying notes? Now you’ve got a generation of people who are still afraid to go into the ocean fifty years later.

John Williams music movies aren't just films with background tracks. They are living, breathing collaborations where the score is as much a character as the actors on screen.

The Spielberg-Williams Brotherhood

It all started back in 1974 with a movie called The Sugarland Express. A young Steven Spielberg reached out to Williams because he loved what he did for a film called The Reivers. They hit it off immediately. It wasn't just a professional gig; it became what Spielberg calls a "brotherhood."

They’ve done almost thirty movies together. Think about that for a second. That kind of longevity is basically unheard of in Hollywood.

The Shark That Shouldn't Have Worked

When Williams first played the Jaws theme for Spielberg on a piano, Spielberg actually laughed. He thought it was a joke. He was expecting something "piratey" or grand. Instead, Williams gave him something primal.

- It’s just an E and an F.

- It sounds like a heartbeat.

- It sounds like something approaching.

Spielberg later admitted that Williams’ music did more for the movie than the actual shark did. Because the mechanical shark (nicknamed Bruce) rarely worked, they had to hide it. The music became the shark. It told you when the danger was there even when you couldn't see a thing. That is the definition of storytelling through sound.

Changing the Game with Star Wars

By 1977, symphonic scores were kinda considered "old hat." The industry was moving toward pop soundtracks and gritty realism. Then George Lucas—on a recommendation from Spielberg—hired Williams for a little space opera.

🔗 Read more: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

Williams went the opposite direction of the disco trends. He looked back to the Golden Age of Hollywood, using a massive orchestra to create leitmotifs. If you don't know the term, a leitmotif is basically a musical "tag" for a character or an idea.

- Luke Skywalker’s Theme: Heroic, soaring, full of hope.

- The Imperial March: (Technically debuted in The Empire Strikes Back)—heavy, oppressive, and immediately tells you Vader is in the room.

- The Force Theme: Melancholic but spiritual.

When that title crawl hit with the opening fanfare, it changed everything. It didn't just save the movie; it revived the entire concept of the orchestral film score.

The Secret Life of "Johnny" Williams

Most people think John Williams just appeared out of nowhere to write Star Wars, but he’s been in the trenches since the 1950s. Back then, he went by "Johnny" Williams.

Before he was the Maestro, he was a killer jazz pianist. You can actually hear him playing piano on the soundtracks for West Side Story (the 1961 original) and To Kill a Mockingbird. He even wrote the theme songs for TV shows like Gilligan’s Island and Lost in Space. Yeah, the guy who wrote Schindler’s List also wrote the music for "The Skipper" and "Little Buddy." Life is weird like that.

He Still Writes by Hand

In an age where every composer is using MIDI, synthesizers, and complex computer software, John Williams is still sitting at a wooden desk with a pencil and staff paper.

He doesn't use a computer. He doesn't like them.

He sits at his piano, tries out melodies, and writes them down. There’s something incredibly human about that. When you hear the London Symphony Orchestra playing his work, you’re hearing something that was literally hand-crafted. It’s not "rendered"; it’s composed.

💡 You might also like: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

Why 2026 is a Big Year for the Maestro

Even at 93 years old, Williams isn't exactly slowing down. We recently saw the release of the documentary Music by John Williams, which has been cleaning up on the awards circuit. It’s actually nominated for a 2026 Grammy for Best Music Film.

He’s also finally being integrated into the Star Wars theme parks in a way fans have wanted for years. Starting in Spring 2026, Disney is adding his iconic scores to the background soundscapes of Galaxy's Edge. For a long time, the parks only used "diegetic" sound (meaning sounds that would "actually" be in that world, like droids or aliens), but they realized that walking through a Star Wars land without John Williams music felt, well, a little empty.

The "Final" Score?

For a minute there, Williams said Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023) was going to be his last movie. Everyone got all sentimental. But then, in true artist fashion, he basically said, "Actually, never mind."

He’s realized that he can't really "leave" music. It’s how he breathes. While he might not be doing the 14-hour days required for every blockbuster anymore, he’s still involved in concert music and consulting.

The Nuance of the "Williams Sound"

Some critics—mostly the "stodgy" classical music types—used to look down on film music. They thought it was "manipulative" or "lesser" than a symphony.

But Williams bridged that gap. He became the conductor of the Boston Pops and forced the classical world to take film music seriously. He started putting film scores in the first half of the program, which was usually reserved for "serious" composers like Beethoven or Tchaikovsky.

It’s Not All Fanfares

While everyone knows the big "hero" themes, his real genius often shows up in the quiet moments.

📖 Related: Cómo salvar a tu favorito: La verdad sobre la votación de La Casa de los Famosos Colombia

- Schindler’s List: He originally told Spielberg, "You need a better composer than me for this." Spielberg replied, "I know, but they’re all dead." Williams wrote a haunting, violin-led piece that captures the immense grief of the Holocaust without being melodramatic.

- Catch Me If You Can: This is where his jazz roots shine. It’s cool, rhythmic, and feels exactly like a 1960s caper.

- Harry Potter: "Hedwig’s Theme" uses a celesta to create a sound that is literally "magical." It’s light, twinkly, and slightly mysterious.

Actionable Steps for Music Lovers

If you want to truly appreciate what John Williams has done, you can’t just listen to the "Best Of" playlists. You have to look a little deeper.

Listen to the "un-film" works. Williams has written concertos for everything from the tuba to the harp. His Violin Concerto No. 2, written for Anne-Sophie Mutter, shows a much more modern, complex side of his brain that you don't always hear in Jurassic Park.

Watch the movies with "Isolated Score" tracks. Some Blu-rays and special editions allow you to turn off the dialogue and sound effects so you only hear the music. Watching the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark this way is a masterclass in timing and tension.

Check out the 2026 Grammy-nominated documentary. If you haven't seen Music by John Williams on Disney+ yet, do it. It features home movies provided by Spielberg himself showing Williams in the middle of the creative process. It's the closest we'll ever get to seeing how the magic actually happens.

Experience it live. Many orchestras around the world now do "Film in Concert" nights where they play the entire score live while the movie projected on a screen. There is nothing—absolutely nothing—like hearing a live horn section nail the Superman theme.

Ultimately, the reason John Williams music movies remain the gold standard is because he never treats the audience like they're stupid. He uses complex harmonies and sophisticated orchestration to tell stories that feel universal. He made the orchestra cool again. And honestly? He’s probably the reason half the people in your local symphony picked up an instrument in the first place.

To get the full picture, go back and listen to his 1960s jazz work under the name Johnny Williams. Compare that to the "wailing woman" vocal techniques he used in Munich (2005). The range is staggering. You’ll start to hear the DNA of his later masterpieces in those early piano riffs, proving that even a legend has to start somewhere.