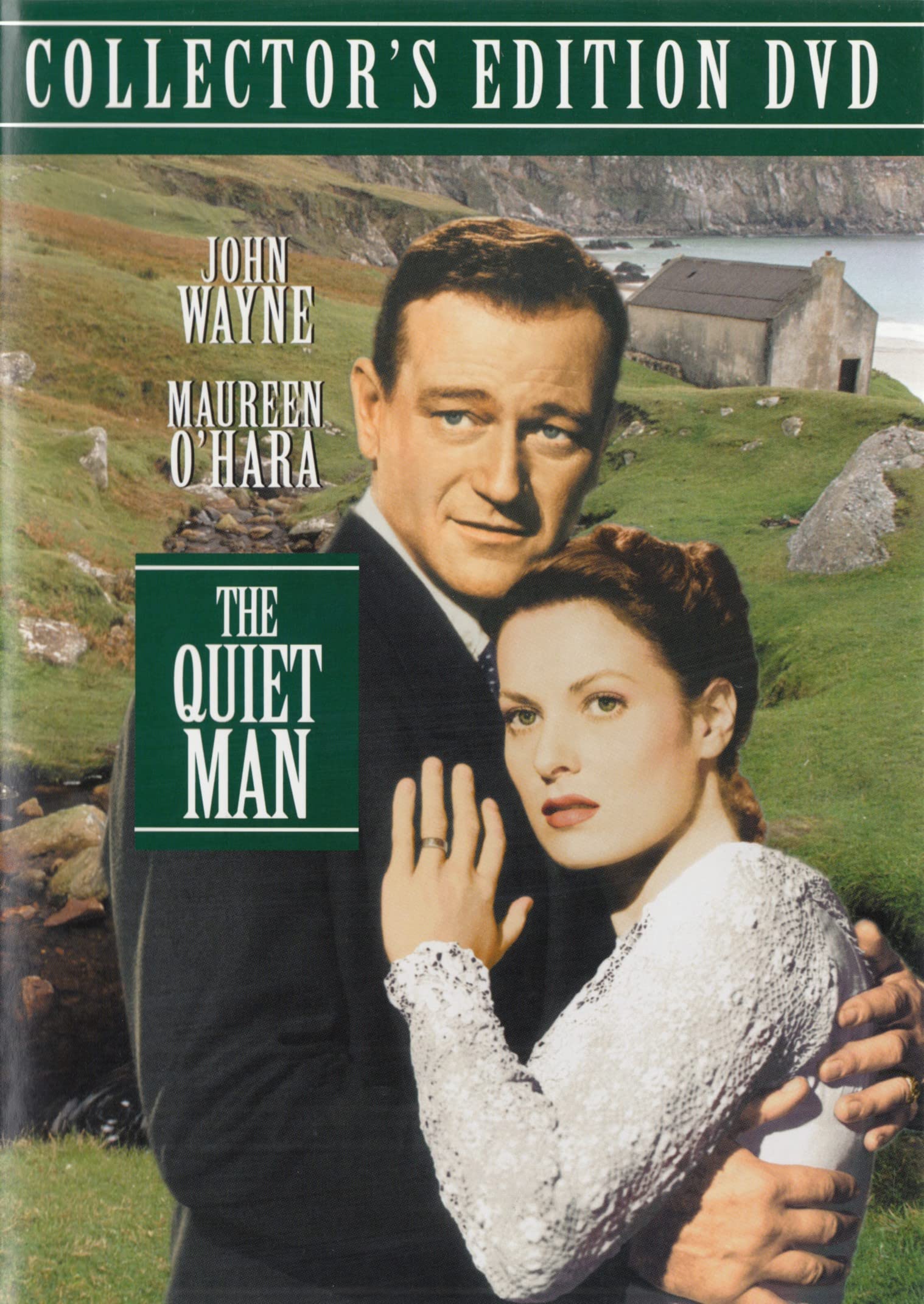

John Wayne didn't always play the cowboy. Sure, he’s the face of the American West, but if you ask a true fan for his best work, they won’t point at a dusty trail in Texas. They’ll point to the lush, emerald hills of County Mayo.

John Wayne The Quiet Man is a weird, beautiful anomaly in cinema history. It’s a movie that took fifteen years to get made because Hollywood suits thought it was "too Irish" or "too artsy." They were wrong. It became a smash hit, a Technicolor dream that defined Ireland for the world, even if that Ireland never quite existed outside of John Ford’s imagination.

Honestly, the film is basically a fairy tale for grown-ups.

The Fight to Make a "Small" Movie

John Ford, the legendary director, was obsessed with Maurice Walsh’s short story. He bought the rights for a measly ten dollars back in 1933. But nobody wanted to fund a movie about a retired boxer going home to Ireland to buy a cottage. It didn't have enough guns. It didn't have enough "Duke."

To get the green light, Ford and Wayne had to make a deal with Republic Pictures—a "Poverty Row" studio known for cheap B-Westerns. The boss, Herbert J. Yates, basically told them: "Make me a Western first, then you can have your Irish movie." So, they made Rio Grande (1950) just to pay the bills.

👉 See also: Why the All Creatures Great and Small TV Series DVD is Still the Best Way to Visit Darrowby

When they finally got to Ireland in 1951, they weren't just making a film. They were having a homecoming. Ford’s family was from Galway, and you can feel that personal connection in every frame. He wasn't just directing; he was painting a love letter to a land he’d heard about in stories.

That Electric Chemistry

You’ve seen the posters. John Wayne, massive and rugged, dragging a fiery Maureen O’Hara across a field. People often assume they were a couple in real life because the heat between them was so real. They weren't. They were just the best of friends.

O’Hara was one of the few women who could actually stand up to Wayne's screen presence. She famously said she was the only leading lady "big enough and tough enough" for him. If he raised a hand, she didn't cower; she looked like she’d take his head off.

The Naughty Secret

There’s a famous bit of trivia from the final scene. As the movie ends, Maureen O’Hara whispers something in Wayne’s ear. His jaw drops. He looks genuinely shocked. For decades, fans wondered what she said.

Years later, it came out that Ford had told her to say something incredibly "naughty" to Wayne to get a real reaction. Whatever she said, she took it to her grave. It’s one of those perfect movie moments that you just can't script.

The "Quiet" Man Who Wasn't That Quiet

Let's talk about the plot for a second. Sean Thornton (Wayne) is a boxer who killed a man in the ring. He’s haunted. He wants peace. He wants "The White O'Morn," his family's old cottage.

But Ireland has rules. Ancient, stubborn rules.

He falls for Mary Kate Danaher, but her brother Will (played by the incredible Victor McLaglen) is a bully who refuses to give up her dowry. In Seán’s American eyes, the money doesn't matter. He’s rich! He doesn't need a few gold sovereigns.

But to Mary Kate, it’s not about the cash. It’s about her independence. Her "stuff"—the furniture, the linens, the gold—is her only claim to being a person in a patriarchal society. Seán’s refusal to fight for it isn't seen as "peaceful" by the locals; it’s seen as a lack of respect for her.

The Epic Brawl

The movie culminates in what is arguably the most famous fistfight in movie history. It’s long. It’s messy. They stop for a drink halfway through. They tumble through haystacks and rivers.

🔗 Read more: The World in My Grasp: Why This Short-Form Drama Is Actually Taking Over

By the end, Seán and Will are best friends. It’s a very "Fordian" way of solving problems. You punch each other until the air is cleared, then you go have a pint. Is it realistic? Probably not. Is it satisfying? Absolutely.

Visiting Innisfree Today

The fictional village of "Innisfree" was actually the town of Cong in County Mayo. If you go there today, you’ll find a cottage museum that’s an exact replica of the movie set. You can visit the "Quiet Man Bridge" in Oughterard, which still has a plaque featuring Wayne.

Sadly, the original "White O'Morn" cottage—the one Seán buys in the film—fell into total ruin. For years, it was just a pile of stones. There have been countless campaigns to restore it, but it remains a symbol of how time moves on, even when we want to freeze it in 1952.

What Most People Get Wrong

Some modern critics look at The Quiet Man and see a dated, sexist movie. They see Seán dragging Mary Kate through the mud and cringe.

But if you look closer, Mary Kate is the one driving the action. She refuses to sleep with him until she gets her rights. She manipulates the situation to force Seán to stand up for her. In many ways, she’s the strongest character in the film.

It’s also surprisingly progressive for 1952 in how it treats religion. The Catholic priest (Ward Bond) and the Protestant vicar (Arthur Shields) are best friends who conspire to help the lovers. In a country defined by religious tension, Ford showed a version of Ireland where everyone actually got along.

Actionable Steps for Fans

If you want to experience the film beyond just watching it on St. Patrick's Day, here is how to do it right:

- Watch the 4K Restoration: The Technicolor in this movie won an Oscar for a reason. Don't watch a grainy YouTube rip. Find the high-definition restoration to see those greens pop.

- Listen to the Soundtrack: Victor Young’s score is a masterpiece of folk-inspired orchestral music. It’ll stay in your head for weeks.

- Visit Cong (Virtually or In-Person): Look up the Ashford Castle grounds. It’s where many of the outdoor scenes were filmed, and it’s now one of the most luxurious hotels in the world.

- Read the Original Story: Maurice Walsh's short story is different in many ways—it’s grittier and more political. It adds a whole new layer to Seán’s character.

The film remains a "diaspora dream." It’s what every Irish-American immigrant hoped Ireland was like—a place where the hills are always green, the beer is always cold, and the fights always end with a smile. It’s not a documentary. It’s a poem. And that’s why we’re still talking about it seventy-plus years later.