Ever feel like your brain just... hit a wall? You’re trying to learn a new software interface or maybe just following a complicated recipe, and suddenly, you can’t process a single word. You aren't getting "dumber." Your hardware is fine. It's your RAM. Or, as Australian educational psychologist John Sweller would put it, your working memory has reached its absolute limit.

John Sweller cognitive load theory isn't just some dusty academic concept from the 1980s. It’s basically the "Law of Gravity" for how humans learn anything. If you ignore it, your teaching, your presentations, and your own self-study sessions will fail. Period. Sweller realized back in 1988 that our brains have a massive bottleneck. While our long-term memory is virtually infinite, our working memory—the part we use to actually "think"—is tiny.

📖 Related: High heat zip ties: Why your standard nylon wraps are melting and what to use instead

Think of it like this. Long-term memory is a massive warehouse. Working memory is a small, cluttered workbench. If you try to pile twenty heavy projects onto that workbench at once, everything falls off.

The Three Flavors of Mental Strain

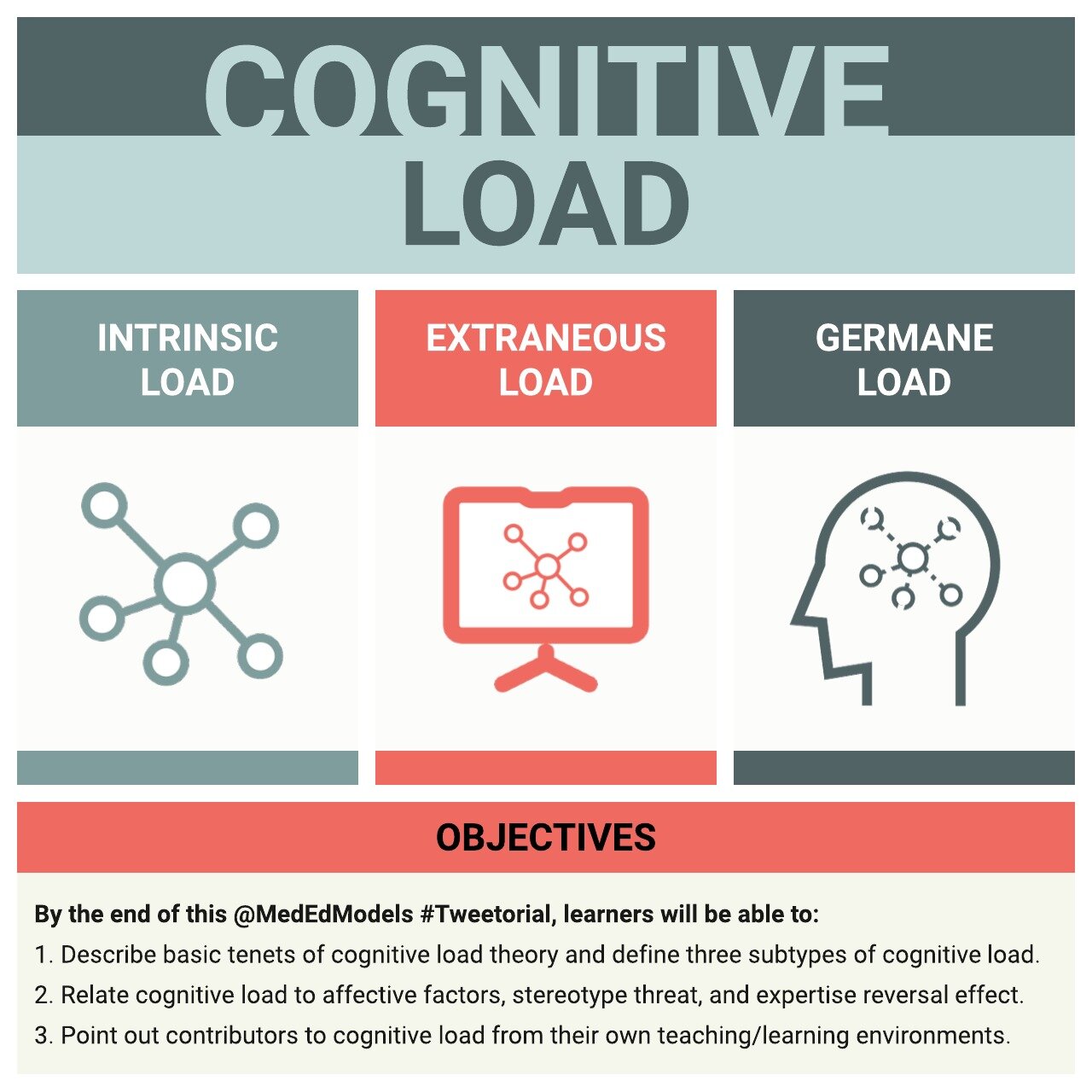

Sweller didn't just say "learning is hard." He broke down why it's hard into three specific types of load. Understanding the difference between these is usually the "aha!" moment for most designers and teachers.

First, there is Intrinsic Load. This is the inherent difficulty of the topic. Learning $1 + 1 = 2$ has a low intrinsic load. Learning quantum chromodynamics has a high one. You can't really "fix" intrinsic load without simplifying the subject matter itself. It is what it is.

Then comes Extrinsic Load. This is the villain of the story. It’s the unnecessary mental effort caused by bad design. If you are reading a textbook and the diagram is on page 5 but the explanation is on page 7, your brain wastes energy flipping back and forth. That "travel time" for your eyes and mind is extrinsic load. It’s garbage noise. It does nothing for your learning.

Finally, we have Germane Load. This is the "good" kind of work. It’s the effort your brain puts into building "schemas"—mental frameworks that help you organize information. When you start seeing patterns and connecting new info to things you already know, that’s germane load at work.

The Split-Attention Effect is Killing Your Productivity

One of Sweller’s most famous findings is the Split-Attention Effect. It’s incredibly common.

Imagine you’re watching a tutorial video. The narrator is talking about a specific button on the screen, but they haven't highlighted it. You’re frantically scanning the UI while trying to listen to their instructions. Because your attention is split between the visual search and the auditory processing, you learn less of both.

In a 1991 study, Sweller and his colleagues (specifically Chandler and Sweller) found that students performed significantly better when instructions were integrated directly into diagrams rather than being listed in a separate key.

👉 See also: How to get rust out of a fuel tank without ruining your engine

It sounds obvious, right?

Yet, walk into any corporate training session today. You’ll see a PowerPoint slide with a complex chart and a speaker talking about something related but not identical. The audience's brains are screaming. They are burning all their glucose just trying to figure out which part of the chart the speaker is referencing.

Why Experts Make Terrible Teachers

There’s a weird quirk in John Sweller cognitive load theory called the Expertise Reversal Effect.

It’s a bit of a slap in the face for experts.

Basically, the instructional techniques that help a beginner will actually hurt an expert. Beginners need "worked examples"—step-by-step guides that show exactly how to solve a problem. Experts, however, already have those schemas in their long-term memory. When you give an expert a worked example, their brain tries to reconcile your steps with their own internal steps. This creates—you guessed it—extrinsic load.

Basically, you’re cluttering their workbench with tools they already own. If you want to teach an expert, give them a problem to solve. If you want to teach a novice, show them the solution first.

The Redundancy Effect: Stop Reading Your Slides

If you take one thing away from Sweller's work, let it be this: Stop reading your slides out loud. When you present a slide full of text and then read that text verbatim, you are sabotaging your audience. The human brain processes text as visual information (even though we "hear" it in our heads). When we hear the same words simultaneously, it creates a "Redundancy Effect." The brain has to process the same information through two different channels at slightly different speeds.

It’s exhausting. It’s why people tune out in meetings.

Actually, research shows people learn better from a simple graphic paired with a spoken explanation than from a graphic, a spoken explanation, and on-screen text all at once. Less is literally more.

Practical Ways to Hack Your Brain

So, how do you actually use this? Honestly, it’s about being ruthless with what you include.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened When Crypto Started and Why It Wasn't Just Bitcoin

- Integrated Diagrams: If you’re making a guide, put the labels on the parts of the image. No legends. No "See Figure 1."

- The Transient Information Effect: Human speech disappears the moment it’s spoken. If you’re giving complex instructions, give them a permanent reference (like a handout or a static slide) so they don’t have to use working memory just to remember what you said two minutes ago.

- Worked Examples: Before asking someone to do a task, show them three completed versions. Let their brain build a schema before you force them to "act."

Cognitive load isn't a theory you "finish" learning. It’s a lens. Once you see it, you start noticing how much of our modern world—from cluttered websites to chaotic classroom settings—is designed in direct opposition to how the human brain actually functions.

The goal isn't to make things "easy." The goal is to clear the "extrinsic" junk out of the way so the brain has enough room to handle the "intrinsic" challenge of the topic itself.

Actionable Steps for Implementation

To start applying these insights immediately, audit your current communication style or learning habits through these specific lenses:

- Kill the "Legend": Open your latest presentation or report. Find every chart that uses a color-coded key. Delete the key. Move the text labels directly next to the data points or lines they describe. This eliminates the "split-attention" tax on your reader's brain.

- The 5-Second Rule for Slides: If a viewer cannot understand the core point of your slide within five seconds, the cognitive load is too high. Remove the decorative icons. Trim the sentences into fragments. If you need the detail, put it in the "notes" section for later.

- Sequence Your Teaching: If you are training someone on a complex task, use the "fading" method. First, show them a fully worked-out example. Next, give them a problem where half the steps are done. Finally, give them a blank problem. This gradually shifts the burden from your guidance to their own developing schemas.

- Audio-Visual Synergy: If you are recording a video or giving a talk, use images to show and your voice to explain. If you must have text on screen, stop talking while the audience reads it. Give them the "silence to process" so their auditory and visual channels aren't fighting for the same limited working memory resources.