If you walked into the Paris Salon in May 1884, you wouldn’t have seen a masterpiece. Well, you would have, but you wouldn’t have known it yet. Instead, you would have heard a lot of whispering. A lot of tut-tutting. Probably some genuine, red-faced outrage from people in top hats and corsets.

John Singer Sargent 1884 was supposed to be the year he conquered the art world. He was thirty, talented, and frankly, a bit of a golden boy. But he made a mistake. He painted Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, an American socialite in Paris, and he painted her exactly as she was: ambitious, striking, and undeniably provocative.

He called it *Portrait de Mme ***. We know it today as Madame X.

It’s hard for us to grasp why a strap falling off a shoulder caused a national crisis in France. We live in an era of "naked dresses" on the red carpet. But in 1884, that single slipped jeweled strap was a bridge too far. It suggested she was "falling out" of her dress. It suggested she was available. It suggested, in the eyes of the French elite, that Sargent had no respect for the decorum that kept their high society glued together.

The Scandal That Ruined a Reputation

Sargent didn't just paint a woman. He painted a vibe. Gautreau had this bizarre, lavender-tinted skin—some say she used arsenic wafers to get that pale—and he captured that deathly, aristocratic glow perfectly. The contrast between her white skin and that ink-black velvet dress is still one of the most arresting things you’ll ever see in a museum.

But the public hated it.

💡 You might also like: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

They mocked her nose. They laughed at her pose. They called the skin "decomposing." Sargent was devastated. He actually tried to fix the painting while it was still hanging in the Salon by painting the strap back up onto her shoulder. It didn’t matter. The damage was done. His commissions in Paris dried up almost overnight. People didn't want to be "Sargent-ed" if it meant being turned into a caricature of scandal.

Honestly, it’s kinda wild how one year can pivot a whole career. If the Salon had loved Madame X, Sargent might have stayed in Paris forever. He might have become just another French academic painter. Instead, the failure of John Singer Sargent 1884 forced him to pack his bags. He fled to London. He spent time in the English countryside, at Broadway in the Cotswolds, trying to figure out if he even wanted to paint portraits anymore.

Why 1884 Changed the Way We See Light

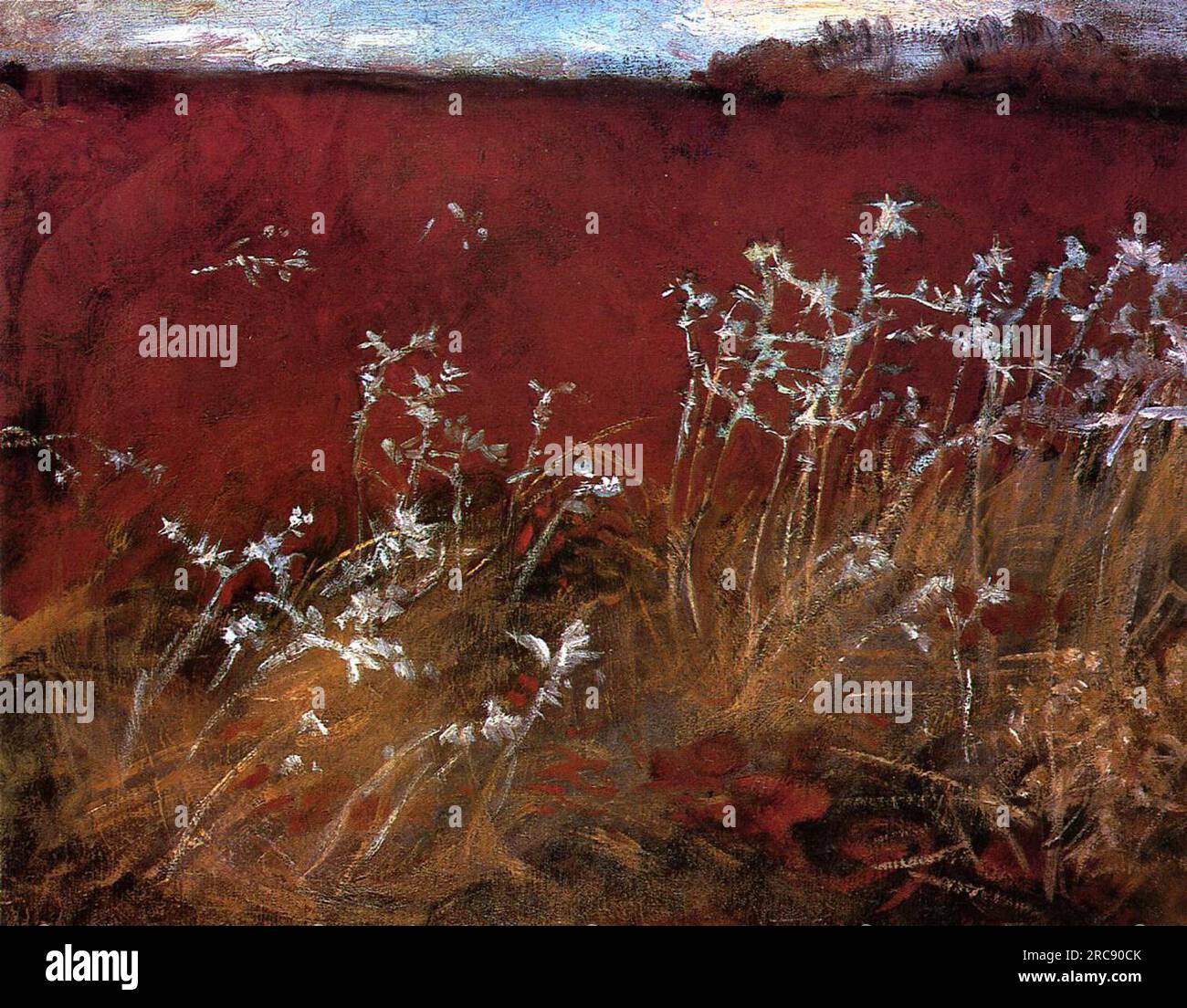

While he was licking his wounds in England, something shifted. Away from the stiff, judgmental eyes of the Paris critics, Sargent started playing with light in a way that felt... free.

He began working on Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose.

If you've seen it, you know it’s the polar opposite of the dark, cynical world of Madame X. It’s just two young girls in a garden, lighting Chinese lanterns at twilight. It’s soft. It’s glowing. It’s innocent. But it took him forever to finish because he only painted for about two minutes every evening when the light was "just right." He would literally drop his tennis racket when the sun hit a certain point and rush to the easel.

📖 Related: Brokeback Mountain Gay Scene: What Most People Get Wrong

This period shows a man transitioning from a desperate-to-please social climber to a true master of atmosphere. He was influenced by Monet, whom he visited at Giverny. You can see the Impressionist DNA starting to weave into his work. He wasn't just recording what a person looked like anymore; he was recording how the air felt around them.

The Business of Being an Artist

Let's talk money and career moves. By the end of 1884, Sargent was technically "canceled" in the French market. Today, we’d say he was "pivoting." He had to rebuild his brand from scratch in a country (England) that initially found his style too "French" and too flashy.

The British public liked their portraits a bit more boring. They wanted to look like their ancestors. Sargent wanted them to look like they were alive.

It took a few years, but the gamble paid off. By the 1890s, he was the most sought-after portraitist in the world. But that foundation—that realization that he could survive a public shaming—was forged in the fires of 1884. He eventually kept Madame X in his studio for decades. He didn't sell it until 1916, when he gave it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He told the director, "I suppose it is the best thing I have done."

He knew. Even when the world was screaming that he’d failed, he knew he’d captured something eternal.

👉 See also: British TV Show in Department Store: What Most People Get Wrong

What You Should Take Away From This Era

If you’re looking at Sargent's work from this period, don’t just look at the faces. Look at the edges.

- The "Lost" Edges: Look at where a sleeve meets the background. Sargent was a master of making things disappear into the shadows so your eye focuses on the highlights.

- The Palette: Notice the shift from the cold, acidic tones of the Gautreau portrait to the warm, floral hues of his English studies.

- The Narrative: Every painting from 1884 is a story of a man trying to find his voice after being told to shut up.

The lesson here is pretty simple: your biggest public failure might actually be the thing that saves your career. If Sargent hadn't been kicked out of Paris by a wave of moral outrage, we might not have the sweeping, breathtaking murals in the Boston Public Library or the iconic portraits of the Edwardian era.

How to Experience Sargent Today

To really understand the impact of John Singer Sargent 1884, you have to see the scale of these works in person. Reproductions on a phone screen don't do justice to the brushwork.

- Visit the Met in NYC: Go stand in front of Madame X. Notice the strap he repainted. If you look closely, you can sometimes see the ghost of the original "dropped" position. It’s a haunting reminder of his panic.

- Check out the Tate Britain: Look for his mid-1880s English works. See how much softer his soul seems to get when he isn't trying to impress the Parisians.

- Read his letters: If you can find a collection of his correspondence from this year, do it. He was funny, stressed, and deeply human. He wasn't an "Old Master" yet; he was just a guy in his late twenties wondering if he’d just ruined his life.

Understanding the context of 1884 changes how you see every other painting he ever did. It turns a "pretty picture" into a document of survival. He took the "X" the public gave him and turned it into a mark of excellence.

Next Steps for Art Lovers:

To deepen your understanding of this specific pivot point, research the influence of Diego Velázquez on Sargent’s early work. The way Sargent handled blacks and greys in 1884 was a direct homage to the Spanish masters, a technique that allowed him to create depth without relying on heavy colors. Examining the sketches for Madame X—of which there are many—reveals how much he obsessed over the silhouette before a single drop of paint hit the final canvas.