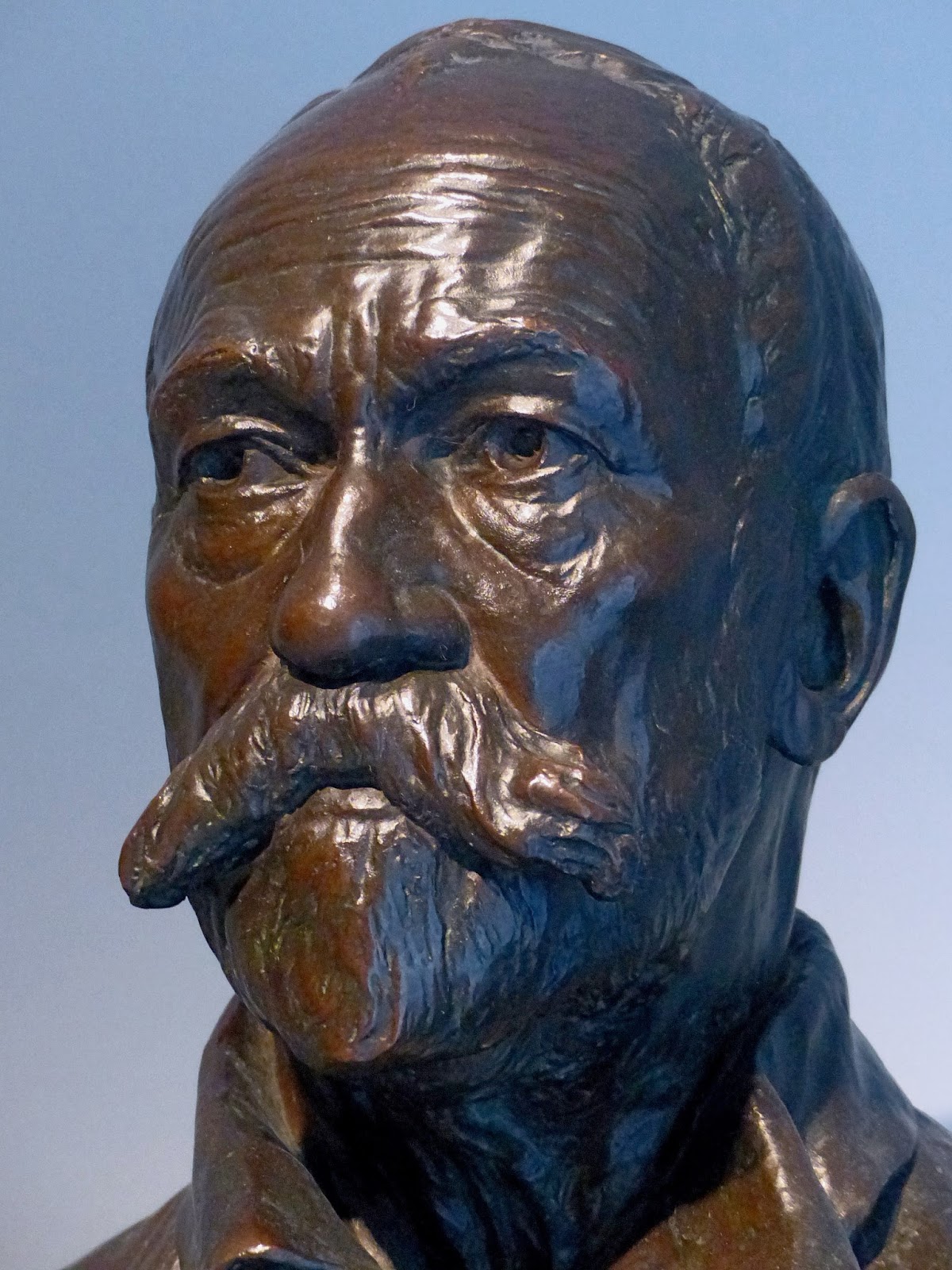

You’ve probably walked past his work without even realizing it. If you’ve ever stood in front of the New York Stock Exchange and looked up at the massive pediment, or wandered through Central Park near the 72nd Street cross-drive, you’ve encountered the bronze and stone legacy of John Quincy Adams Ward. He wasn't just another 19th-century artist with a three-part name. He was the guy who basically decided that American art didn't need to look like a dusty carbon copy of European antiques.

Before Ward showed up, American sculpture was stuck in a bit of a rut. Most artists were obsessed with "Neoclassicism." That’s just a fancy way of saying they wanted everyone to look like a Greek god in a toga, even if the subject was a politician from Ohio. Ward thought that was ridiculous. He wanted grit. He wanted realism. He wanted American art to actually look like, well, Americans.

The Man Who Broke the Italian Mold

Born in 1830 in Urbana, Ohio, Ward didn't follow the typical "starving artist" trajectory. He didn't run off to Rome the first chance he got. Back then, Italy was the place to be if you wanted to be taken seriously. You’d go there, hire some Italian carvers to do the heavy lifting, and send the finished marble back to the States. Ward hated that idea. He stayed home. He learned the technical, messy side of the craft—the casting, the founding, the literal heavy lifting of bronze.

His apprenticeship under Henry Kirke Brown in Brooklyn was the turning point. Brown was already pushing for a more naturalistic style, and Ward took that ball and ran with it. By the time he opened his own studio in New York in 1861, he was ready to challenge the status quo.

It's hard to overstate how weird it was for an artist of his caliber to stay in the U.S. at the time. It was a statement. He was basically saying that American soil and American subjects were enough. You didn't need a Mediterranean breeze to create something timeless.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

The Indian Hunter and the Central Park Revolution

Let’s talk about The Indian Hunter. This is arguably his most famous piece, and for good reason. If you go to Central Park today, you’ll see it—a bronze figure of a Native American man with a dog, leaning forward in a tense, predatory crouch. It was the first statue by an American sculptor to be placed in Central Park, back in 1869.

Most people don't realize how radical this was. Instead of a static, stiff pose, Ward captured motion. You can almost feel the muscles twitching. To get the details right, Ward actually traveled to the Dakotas to study the physiology and clothing of the people he was portraying. While modern eyes might view the "noble savage" trope with a more critical lens, for the 1860s, this level of anatomical accuracy and research was groundbreaking. It wasn't a caricature; it was an observation.

Why John Quincy Adams Ward Changed the Way We See Heroes

One of the toughest things for an artist is making a guy in a suit look interesting. In the mid-1800s, men’s fashion was, frankly, boring. Heavy wool coats, stiff trousers, no flowing robes to hide behind. Ward leaned into it.

Take his statue of George Washington at Federal Hall in Wall Street. You know the one—it stands right where Washington took the oath of office. If a Neoclassical artist had done it, George probably would’ve been wearing a laurel wreath and a chiton. Ward? He put him in the clothes he actually wore. He focused on the weight of the man’s stance. It’s a bronze that feels heavy, not just because of the material, but because of the gravity of the moment it represents.

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

He had this uncanny ability to make bronze feel like skin and fabric. It’s called "painterly" sculpture. He used texture to catch the light, making the surfaces feel alive rather than polished and cold.

The Success of the "Dean"

Ward eventually earned the nickname "The Dean of American Sculpture." He wasn't just making art; he was building the infrastructure for other artists to thrive. He was a founder and president of the National Sculpture Society. He held the presidency of the National Academy of Design. He was involved with the Metropolitan Museum of Art from its earliest days.

He was a powerhouse.

Honestly, he was kind of a workaholic. Even in his late seventies, he was working on massive projects like the Pediment of the New York Stock Exchange. That project actually turned into a bit of a nightmare because the original marble was so heavy it started to threaten the structural integrity of the building. It eventually had to be replaced with copper replicas, but the design—Integrity Protecting the Works of Man—remains a testament to his ambition.

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

The Works You Should Actually Go See

If you’re a fan of art history or just want a cool walking tour, Ward’s work is scattered across the Eastern United States.

- The Seventh Regiment Memorial (Central Park, NYC): This is a haunting depiction of a Civil War soldier. It doesn't celebrate the glory of war; it looks like a man who has seen too much. It’s weary.

- Henry Ward Beecher Monument (Cadman Plaza, Brooklyn): A masterpiece of character study. The way the figures interact at the base of the pedestal tells a whole story about the abolitionist movement.

- General George Henry Thomas (Washington, D.C.): Many critics consider this the finest equestrian statue in the country. The horse looks like it’s actually breathing, and Thomas looks like he’s actually leading.

Ward’s influence is everywhere once you start looking for it. He taught us that American stories were worth telling in their own voice, without a European accent.

Practical Ways to Explore Ward’s Legacy Today

You don't need an art history degree to appreciate what Ward did. You just need to look at the details. If you're interested in seeing his work or learning more about the era of American Realism, here are a few ways to dive in:

- Take a "Ward Walk" in NYC: Start at Federal Hall on Wall Street to see Washington, then head up to Central Park to find The Indian Hunter, The Seventh Regiment Memorial, and the bust of William Shakespeare.

- Study the Foundry Marks: When you see a Ward bronze, look at the base. You’ll often see the mark of the foundry. Ward was meticulous about the casting process, and seeing those marks reminds you that this was as much an industrial feat as an artistic one.

- Compare and Contrast: Find a Neoclassical statue (there are plenty in the Met) and stand it up against a photo of Ward's work. Notice the difference in the eyes and the hands. Ward’s hands always look like they’ve actually worked for a living.

- Visit Urbana, Ohio: If you’re ever in the Midwest, his hometown still honors him. There are smaller works and archives there that give a more personal look at his life before he became the "Dean."

John Quincy Adams Ward lived through the Civil War, the Gilded Age, and the turn of the century. He saw the world change from candlelight to electricity, and he made sure that American art didn't get left behind in the dark. He proved that you don't have to pretend to be a Roman to be a classic.

To really understand the evolution of American public space, you have to understand Ward. He moved art out of the private galleries of the elite and onto the street corners where everyone could see it. He made the "American look" a real thing. Next time you're in a historic American city, look up at the bronze figures guarding the squares. There's a good chance Ward's influence—if not his actual hand—is right there in front of you.