The 1824 election was a mess. Honestly, if you think modern politics is chaotic, you haven't looked closely at the year the United States nearly broke its own democratic gears. We're talking about a four-way race where the guy with the most votes actually lost.

John Quincy Adams won the 1824 election, but he didn't do it at the ballot box. He did it in the smoky rooms of the House of Representatives.

Andrew Jackson, the "Hero of New Orleans," was livid. He had the popular vote. He had the most electoral votes. Yet, he spent the next four years screaming about a "corrupt bargain" that stole the presidency from the people. It changed American history forever, basically birthing the two-party system we're stuck with today.

The Four-Headed Race for the White House

By 1824, the "Era of Good Feelings" was dead. The Federalist Party had vanished, leaving only the Democratic-Republicans, who were now fighting like siblings over an inheritance. Since there was no primary system, four major candidates jumped in.

You had John Quincy Adams, the intellectual Secretary of State from Massachusetts. Then there was Andrew Jackson, the military superstar and Tennessee senator who appealed to the "common man." William H. Crawford, the Treasury Secretary, was the choice of the old-guard party elite, though a stroke during the campaign seriously hampered his chances. Finally, Henry Clay of Kentucky, the "Great Compromiser" and Speaker of the House, ran on a platform of internal improvements called the American System.

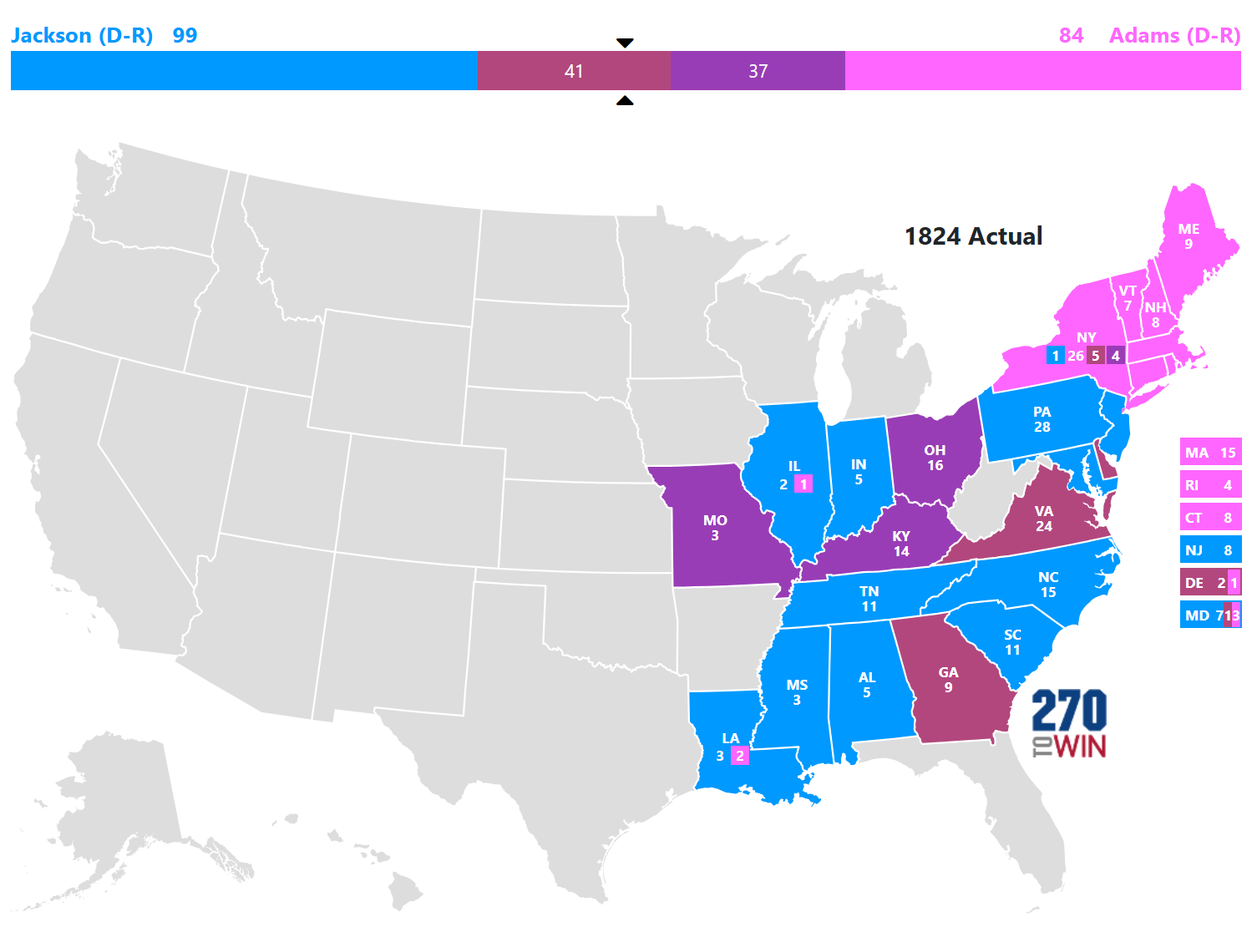

The results were a nightmare for stability. Jackson pulled 99 electoral votes. Adams got 84. Crawford took 41, and Clay trailed with 37.

Because nobody hit the magic number of 131 electoral votes—the majority required by the Constitution—the decision went to the House of Representatives. But there was a catch. Under the 12th Amendment, only the top three candidates were eligible.

Henry Clay, the man who literally ran the House, was out.

📖 Related: Great Barrington MA Tornado: What Really Happened That Memorial Day

Why the House Picked the "Loser"

Imagine being Henry Clay. You’re the Speaker of the House. You just lost your bid for the presidency, but now you’re the kingmaker. You get to decide which of your rivals takes the big chair.

Clay hated Jackson. He saw him as a "military chieftain," a dangerous man with a short fuse who wasn't fit for civil office. Adams, despite being a bit of a cold fish socially, shared Clay’s vision for a strong federal government, national banks, and paved roads.

So, Clay went to work.

He swung the support of the states he controlled over to Adams. On February 9, 1825, the House voted. On the very first ballot, John Quincy Adams was elected President of the United States. He won 13 states, Jackson won 7, and Crawford won 4.

The kicker? A few days later, Adams named Henry Clay as his Secretary of State.

Back then, Secretary of State was the traditional stepping stone to the presidency. Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Adams had all held the job. Jackson’s supporters erupted. They called it the Corrupt Bargain. They claimed Clay had sold the presidency to Adams in exchange for a promotion.

The Fallout of the 1824 Election

Was it actually a backroom deal?

👉 See also: Election Where to Watch: How to Find Real-Time Results Without the Chaos

Historians like Robert V. Remini have argued for decades about this. There’s no "smoking gun" letter where Adams says, "Hey Henry, make me President and I'll give you the job." But the optics were terrible. Even if it was just two guys with similar political goals teaming up, it looked like a total stitch-up.

Adams was a brilliant man, but his presidency was basically dead on arrival.

Jackson’s allies in Congress blocked almost everything Adams tried to do. They spent four years campaigning on the idea that the "will of the people" had been subverted by elite Washington insiders. This grievance fueled the creation of the Democratic Party.

Jackson wasn't just mad; he was organized. His right-hand man, Martin Van Buren, realized that to win in 1828, they needed a massive grassroots machine. They invented the modern political campaign—parades, barbecues, and ruthless mudslinging.

What Most People Get Wrong About 1824

A lot of people assume Jackson "won" the popular vote and was robbed. While he did receive about 151,000 votes compared to Adams' 113,000, we have to remember that in 1824, six states still didn't even have a popular vote for president. In those states, the legislatures picked the electors.

So, the "popular vote" totals from 1824 are actually incomplete.

Also, the 12th Amendment functioned exactly the way it was supposed to. The Founding Fathers were terrified of "the mob." They built the House contingency specifically as a safety valve to ensure a "tempered" choice. Adams won legally, even if he didn't win popularly.

✨ Don't miss: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

The tragedy for Adams was that he was a man of the 18th century trying to lead a 19th-century country. He wanted to build national universities and observatories—he called them "lighthouses of the skies." But the public didn't care about science; they cared about the fact that they felt ignored by the guys in silk stockings.

How to Apply the Lessons of 1824 Today

Understanding who won the 1824 election isn't just a history trivia fact. It’s a blueprint for how political parties die and are reborn. If you’re looking to understand modern political volatility, start here.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Students:

- Study the 12th Amendment: Read the actual text. It explains exactly how a "contingent election" works. If no candidate gets 270 electoral votes today, we go right back to the 1824 rules.

- Trace the Party Roots: Note how the "National Republicans" (Adams/Clay) eventually became the Whigs, while the Jacksonians became the Democrats. The policy divides—big government vs. populist individualism—are still the core of our debates.

- Visit the Primary Sources: Check out the Register of Debates in Congress from February 1825. Seeing the raw transcripts of how the House handled the vote provides a much more visceral sense of the tension than a textbook ever could.

- Analyze the Map: Look at how regionalism dominated. Adams won New England. Jackson won the South and West. Crawford won Virginia and Georgia. This was the beginning of the "sectionalism" that eventually led to the Civil War.

The 1824 election serves as a permanent reminder that in American politics, winning the most votes is sometimes just the beginning of the fight.

Key Takeaways for Quick Reference

- Winner: John Quincy Adams (decided by the House of Representatives).

- The Loser: Andrew Jackson (who had the most popular and electoral votes).

- The Kingmaker: Henry Clay (Speaker of the House).

- The Scandal: The "Corrupt Bargain"—the allegation that Clay traded the presidency for the Secretary of State position.

- Long-term Impact: The end of the "Era of Good Feelings" and the birth of the modern Democratic Party.

To see the direct consequences of this era, examine the 1828 rematch. It remains one of the nastiest, most personal campaigns in the history of the Republic, proving that the grudge from 1824 never truly went away. It essentially set the template for the next two centuries of American power struggles.

For further research into the specific legislative maneuvers of the era, the Library of Congress digital archives contain the personal papers of both Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson, offering a firsthand look at the accusations as they flew in real-time.