John Nash was a ghost. For nearly three decades, a man who had fundamentally reshaped the way we understand human conflict and economic markets wandered the halls of Princeton University, scribbling cryptic equations on chalkboards in the middle of the night. Students called him "The Phantom." They knew he was brilliant, but they didn't know he was a legend who had seemingly vanished into the fog of schizophrenia. Most people know his name because of Russell Crowe’s performance in A Beautiful Mind, but the real john nash mathematician biography is far grittier, more intellectually complex, and honestly, much more tragic than a two-hour movie can capture.

He wasn't just a "math guy." Nash changed how we think about winning and losing. Before Nash, economics was largely built on the idea that everyone just acts in their own best interest. Nash proved that it’s more complicated. He showed that in any competitive situation, there’s a point where no one can improve their outcome by changing their strategy alone—even if the overall result is terrible for everyone. This is the "Nash Equilibrium." It’s why countries keep nukes they don’t want to use and why two coffee shops end up right next to each other on the same corner.

The West Virginia Prodigy and the One-Sentence Recommendation

Nash grew up in Bluefield, West Virginia. He wasn't a child prodigy in the "Mozart" sense; he was just weirdly independent. He read Men of Mathematics by E.T. Bell and started proving things his teachers couldn't explain. When it came time for him to go to Princeton for his doctorate, his professor at Carnegie Institute of Technology wrote him a recommendation letter that was literally one sentence long: "This man is a genius."

That’s it. That was the whole letter.

When he arrived at Princeton in 1948, the math department was the center of the universe. Albert Einstein was walking around. John von Neumann was building the first computers. Nash didn't care. He didn't want to learn from them; he wanted to beat them. He rarely attended lectures. He claimed that sitting in class would spoil his "originality." Instead, he spent his time pacing the hallways or playing "Go" in the common room. He was looking for a problem that was big enough to make him famous.

He found it in Game Theory.

💡 You might also like: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

What the Nash Equilibrium Actually Means for You

Most biographies get bogged down in the notation, but the core of the john nash mathematician biography is a paper he wrote when he was only 21. It was 27 pages long. In those few pages, he provided the mathematical foundation for how we negotiate everything today.

Think about a crowded highway. If everyone drives at 80 mph, everyone gets home fast. But if one person slows down to look at their phone, it creates a ripple. Eventually, everyone is stuck in a jam. The "equilibrium" here is the traffic jam. No single driver can decide to go 80 mph and actually succeed if everyone else is stopped. You are stuck in a sub-optimal reality because of the collective choices of others. Nash proved this mathematically using the Kakutani fixed-point theorem.

$$R_i(s^_{-i}) = s^_i$$

In simple terms, he showed that in any game with a finite number of players, there is always at least one set of strategies where nobody has an incentive to deviate. This changed biology (how animals compete for food), evolution, and especially the Cold War. The Pentagon used Nash’s math to figure out how to keep the Soviet Union in check without actually starting World War III.

The Long Dark: Schizophrenia and the "Phantom" Years

Then things broke.

📖 Related: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

By the late 1950s, Nash was a rising star at MIT. He was "The Kid" everyone feared in an argument. But his mind began to turn on itself. He started believing that The New York Times contained coded messages from extraterrestrials meant only for him. He turned down a prestigious post at the University of Chicago because he believed he was going to be inaugurated as the Emperor of Antarctica.

It’s easy to romanticize this as "tortured genius," but the reality was brutal. He was subjected to insulin shock therapy—a horrific treatment that involved putting a patient into a medically induced coma. He spent years in and out of psychiatric hospitals. His wife, Alicia, stayed by his side through much of it, even when they were divorced. She was the one who kept him from becoming homeless.

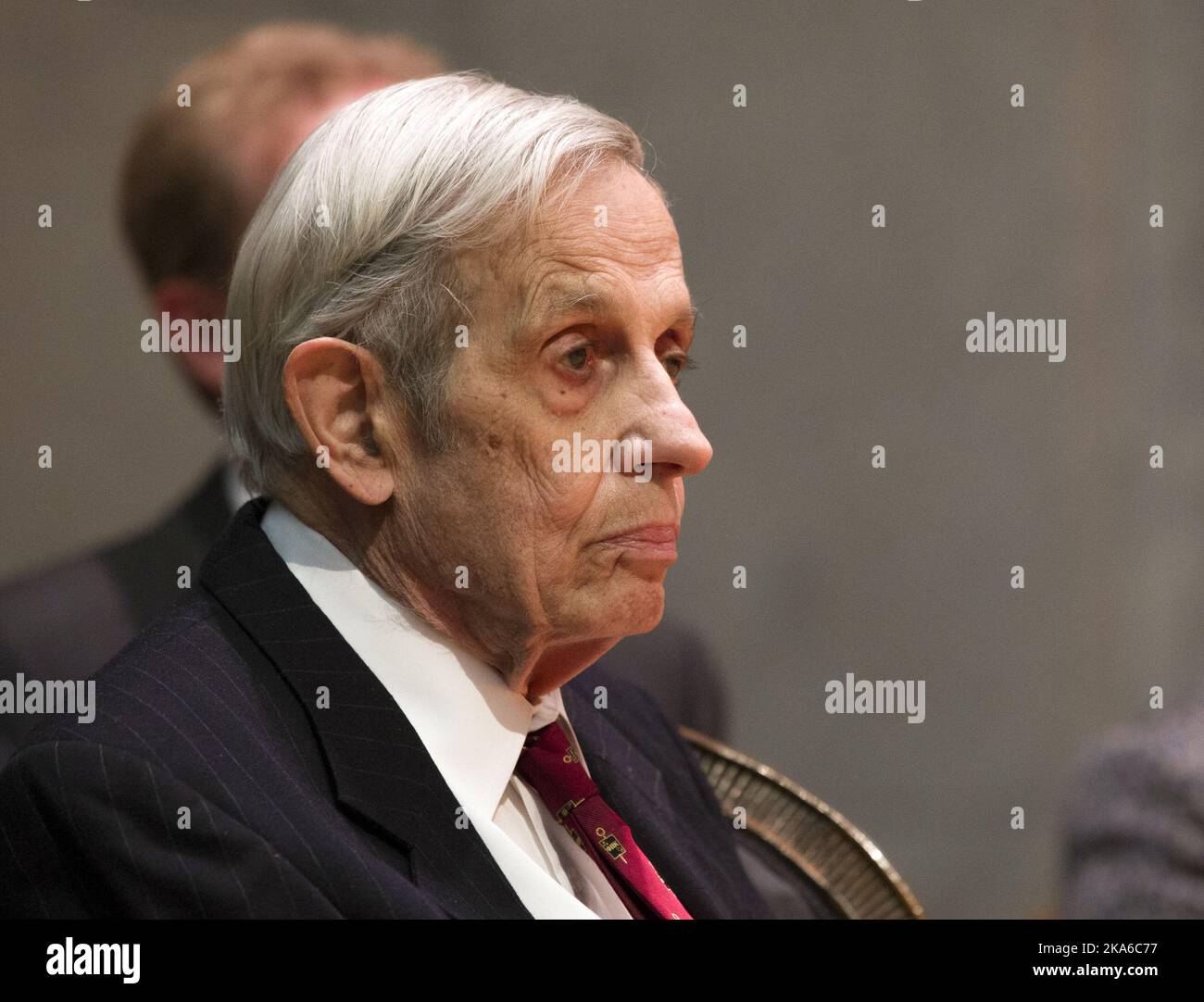

For the 1970s and 80s, Nash was a shadow at Princeton. He’d wear mismatched clothes and leave mysterious messages on blackboards in Fine Hall. He was "the ghost." He wasn't teaching. He wasn't publishing. The mathematical world assumed he was effectively dead.

The 1994 Nobel Prize and the Great Comeback

The most shocking part of the john nash mathematician biography is that he actually got better. Not because of some miracle drug, but because he simply decided to stop listening to the voices. He called it "intellectually rejecting" the delusions. He began to reappear in the world of logic.

In 1994, the Nobel Committee decided to award him the Prize in Economic Sciences. It was a controversial move. Some members of the committee were terrified he would have an episode on stage. They actually changed the rules of how the prize was managed because of him. But he showed up. He was quiet, humble, and lucid.

👉 See also: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

He spent his final years as a respected elder of the Princeton community. He finally got his office back. He finally started talking to students again. He lived long enough to see his life turned into a blockbuster movie, though he famously joked that the movie got the math wrong and made his life look way more glamorous than the cold, hard reality of the hospital wards.

Why His Death Felt Like a Final Twist

In 2015, Nash and Alicia were in Norway where he received the Abel Prize, often called the Nobel Prize for Mathematics. They flew back to New Jersey, hopped in a taxi from the airport, and were heading home. The driver lost control on the New Jersey Turnpike. Both John and Alicia were ejected from the car and killed.

He was 86. She was 82.

It was a sudden, violent end to a life that had finally found peace. But the math he left behind is immortal. Every time you see a price war between two airlines or a treaty signed between two warring nations, you’re seeing John Nash’s brain at work.

Real-World Takeaways from Nash’s Work

If you want to apply Nash's brilliance to your own life or career, you have to look past the symbols.

- Look for the "Lose-Lose" Traps: Nash’s math proves that rational people can end up in a situation that hurts everyone (like a price war). Recognizing a Nash Equilibrium is the first step to breaking it.

- The Power of Cooperation: While Nash focused on non-cooperative games, his work highlights that without a binding agreement, humans default to defensive, selfish strategies. If you want a better outcome, you have to change the "rules" of the game, not just your own moves.

- Resilience is Cognitive: Nash didn't "cure" his mental illness with a pill. He used his own logical mind to categorize his delusions as "false information." It’s a masterclass in the power of the human will to override internal chaos.

To truly understand the legacy of this man, you should look into his 1950 thesis, Non-Cooperative Games. It’s surprisingly readable for a math paper. It reminds us that while the world feels chaotic, there is often a hidden, logical structure beneath the surface—if you’re brave enough to look for it.

Check out the archives at Princeton University or the biography by Sylvia Nasar to see the original letters and notes that built the foundation of modern game theory. His story isn't just about math; it's about the thin line between a mind that sees everything and a mind that sees too much.