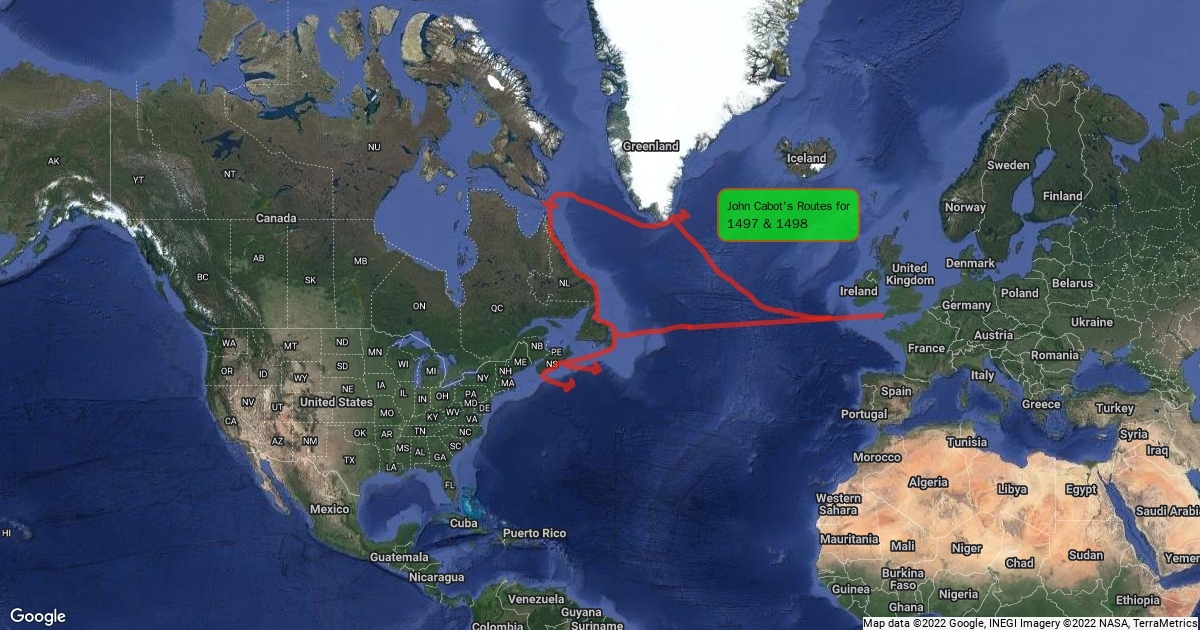

If you’ve ever tried to trace the exact line John Cabot took across the North Atlantic, you’ve probably hit a wall. It's frustrating. We have plenty of statues, plaques, and even a "Cabot Trail" in Nova Scotia, but when it comes to the actual John Cabot maps and routes, the physical evidence is surprisingly thin.

Honestly, we don’t have a single map drawn by Cabot’s own hand that survived. Not one.

What we have is a historical detective story. It's a mix of second-hand letters, a 1500 map by a Spanish cartographer named Juan de la Cosa, and some fascinating (if slightly controversial) archival finds from the University of Bristol’s "Cabot Project." If you want to understand where he actually went, you have to look past the myths of "discovering Canada" and look at the gritty reality of 15th-century navigation.

The 1497 Route: A 35-Day Shot in the Dark

In May 1497, Cabot (or Zuan Chabotto, as his Venetian friends called him) left Bristol on a tiny 50-ton ship called the Matthew. He didn't have GPS. He didn't even have a reliable way to measure longitude.

Basically, his strategy was "latitude sailing." He sailed north to about the same level as the English Channel, then hooked a left across the open ocean.

According to a letter written by a merchant named John Day—which is one of our best sources—the trip took 35 days. They hit land on June 24. This is where things get messy. Where did he actually step off the boat?

- Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland: This is the "official" version. There’s a big statue there. Local tradition is obsessed with it.

- Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia: Many historians argue this makes more sense based on the distance he claimed to have covered.

- Labrador: Some scholars think he hit much further north and then coasted south.

Whatever the case, Cabot was convinced he’d reached the "Seven Cities" or the outskirts of Asia. He stayed for a month, planted a Venetian flag and an English one, and then turned around. He made the return trip in just 15 days—an absolute sprint across the Atlantic—arriving back in Bristol to a hero’s welcome and a £10 reward from King Henry VII. That doesn't sound like much now, but it was a decent chunk of change back then.

💡 You might also like: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

Why Do We Use the Juan de la Cosa Map?

If Cabot’s maps are gone, why do you always see a specific green-and-gold map in history books? That’s the Juan de la Cosa map of 1500.

De la Cosa was a Spanish navigator who had sailed with Columbus. His map is the earliest known world map to show the Americas. If you look closely at the North Atlantic section, there’s a line of five English flags. Those flags represent Cabot’s 1497 discoveries.

It’s the closest thing we have to a contemporary visual of the John Cabot maps and routes. It shows a coastline that stretches quite a way—suggesting Cabot did a lot more "coasting" than just landing and leaving. It labels places like "Sea discovered by the English" and "Cape of the English."

But here’s the kicker: de la Cosa probably got his info from Spanish spies. The Spanish were terrified Cabot was encroaching on their territory. They were watching him like hawks.

The 1498 Mystery: Did He Actually Die?

For a long time, the story was simple: Cabot left in 1498 with five ships, got caught in a storm, and was never seen again. Case closed.

Except, it might not be.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Lake Placid Town Map Doesn’t Tell You

Recent research by Dr. Evan Jones and Margaret Condon has turned up evidence that some of the guys on that 1498 voyage might have actually made it back. They found records suggesting Cabot was back in England around 1500. There's even a weirdly specific theory that he (or his crew) sailed as far south as the Caribbean or even Venezuela, possibly running into Spanish explorers.

There is also a record of a Bristol merchant named William Weston leading a voyage to the "New Found Land" in 1499. If Cabot was dead or lost, why was his right-hand man still making trips? It suggests the John Cabot maps and routes were being actively used and updated by Bristol sailors well into the turn of the century.

Finding the "Missing" Charts

You might wonder why a guy would go to the trouble of finding a new continent and then lose the map.

Part of it was secrecy. These routes were trade secrets. Bristol merchants didn't want the Portuguese or Spanish knowing exactly where the "sea of fish" was. (Cabot had reported that the cod were so thick you could catch them by just dropping a weighted basket into the water).

Another part was his son, Sebastian Cabot.

Sebastian was a bit of a glory-hound. He spent much of his later career in Spain and England taking credit for his father’s work. There’s a famous map from 1544 attributed to Sebastian, but it’s full of contradictions. He basically tried to rewrite history to make himself the primary discoverer. In doing so, he might have obscured or let his father's original documents rot away.

👉 See also: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

What Most People Get Wrong

People often talk about Cabot as if he were an English explorer. He wasn't. He was a Venetian who couldn't get funding in Italy or Spain, so he moved to Bristol because they were already interested in "The Isle of Brasil"—a mythical land they'd been hunting for since the 1480s.

Also, he wasn't looking for "Canada." He was looking for Japan (Cipango).

When he saw the rugged, pine-covered cliffs of the North Atlantic, he didn't think "What a great place for a timber industry." He thought, "Where are the spice markets?" He died (whenever that was) probably feeling like a bit of a failure because he hadn't found the gold and silks he promised the King.

How to Track the Routes Yourself

If you’re interested in the actual geography, don't just look at one map. You've got to compare a few different things:

- Study the John Day Letter (1497): This is the most "raw" data we have on the route. It mentions the "Dursey Head" departure point in Ireland.

- Check the "Cabot Project" Archives: The University of Bristol has digitized a lot of the newer findings that challenge the "lost at sea" narrative.

- Look at the 1544 Sebastian Cabot Map: Even though it's biased, it gives you a sense of what the Cabot family wanted people to believe about their route.

- Visit Cape Bonavista or Cape Breton: If you actually stand on these cliffs, you'll see why the navigation was so treacherous. The "Labrador Current" pushes ships south, which is why landfall is so hard to predict even today.

The real "map" of John Cabot isn't on parchment anymore. It's written into the customs accounts of Bristol merchants and the frantic letters of Spanish ambassadors. The routes were real, the landing happened, and the maps existed—they just weren't meant for us to see. They were meant for the men who wanted to own the sea.

To dig deeper into the actual documents, look up the "The Quinn Papers" or the specific archival work of the Cabot Project. These researchers have spent decades in the "chancery" files of the UK National Archives, pulling out single slips of paper that prove Cabot was a real, debt-dodging, ambitious merchant-explorer rather than just a ghost in a history book.