When you pick up a book by John Berger, you aren't just reading a story. You're entering a protest. Honestly, that’s exactly what John Berger From A to X feels like—a quiet, ink-stained rebellion bound in 200 pages. It isn't a typical novel. It’s a collection of letters.

A’ida is a pharmacist. She lives in Suse, a town that feels like it could be in Palestine, or maybe Latin America, or perhaps a forgotten corner of the Balkans. Her lover, Xavier, is a political prisoner serving two life sentences. He is the "X" of the title. She is the "A."

Most people think this is just a sad book about long-distance longing. They’re kinda wrong. It’s actually a manual for how to stay human when everything around you is designed to crush your spirit.

The Mystery of the Letters

The book starts with a weirdly convincing frame. Berger claims he "recuperated" these letters from a disused prison cell. It’s a classic literary trick, but here it feels heavy. Urgent.

We see A’ida’s letters to Xavier, but we never see what he writes back. Instead, we see his notes scribbled on the backs of her envelopes. These aren't love notes. They’re fragments of political philosophy, observations on gravity, and musings on the global economy.

Why the format is so jarring

The timeline is a mess. The letters aren't in order.

Sometimes A’ida talks about the price of fruit or a neighbor’s broken radio. Then, she mentions Apache helicopters or "the market" like it's a monster breathing down their necks. This back-and-forth between the mundane and the terrifying is Berger’s signature move. He wants you to see that a shared meal is just as political as a protest march.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

You’ve probably noticed how some books feel "manufactured." This one feels grown. It feels like something pulled out of the dirt.

What Most People Get Wrong About John Berger From A to X

A lot of critics at the time—back when it was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2008—complained that the characters lacked "depth." They wanted more backstory. They wanted to know exactly what Xavier did to get two life sentences.

But that’s missing the point.

Berger isn't interested in the "why" of the crime. He’s interested in the "how" of the survival. By keeping the location nameless and the "enemy" faceless, he makes the story universal. The "they" in the book are the same "they" people face everywhere: the military-industrial complex, the IMF, the WTO. Xavier’s notes are full of these acronyms.

Small acts of resistance

In one of the most famous bits, A’ida describes a woman who sees her dead lover on television months after he was killed. It’s a tiny, devastating moment. It shows how trauma isn't a single event but a lingering ghost.

A’ida also draws hands. She draws them over and over.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

- Hands holding pens.

- Hands mixing medicine.

- Hands that can no longer touch the person they love.

These sketches—which are actually in the book—remind us that we are physical beings. In a world of digital surveillance and abstract "targets," Berger insists on the importance of the skin, the bone, and the heartbeat.

The Politics of Tenderness

Is it a political tract? Sorta.

Is it a love story? Absolutely.

Xavier writes about how "precariousness is our strength." That’s a wild thought, right? Usually, we think of being precarious as a weakness. But Berger argues that because the oppressed have nothing to lose, they have a type of freedom the powerful can never understand.

The "Suse" atmosphere

The town of Suse is dusty. It’s hot. There are checkpoints.

Life there is a series of "irregularities." Berger loves that word. He thinks the powerful are scared of things that don't fit into a spreadsheet. A’ida’s letters are irregular. Her love is irregular.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Some readers find the political rants in Xavier’s notes a bit much. They can feel a bit "sentimental" or "preachy" if you aren't in the mood for Marxist theory. But if you look at them as the only way a man in a cage can keep his mind sharp, they make total sense.

Why you should read it now

We live in a world of walls. Whether they are literal walls at borders or digital walls of algorithms, we are being separated.

John Berger From A to X is a bridge. It’s a reminder that even if you can’t change the regime, you can change how you look at a piece of bread or a stray cat.

- It teaches you to pay attention.

- It proves that love isn't just a feeling; it's a form of endurance.

- It shows that the "global" is always "personal."

Honestly, it’s a tough read if you want a happy ending. There is no rescue mission. No sudden pardon. There is just the next letter. And the next.

Actionable Insights for Readers

If you’re going to dive into this book, don’t try to read it like a thriller. You’ll get frustrated.

- Read it slowly. One letter at a time. Let the imagery sink in.

- Look at the drawings. Don't skip them. They are part of the "text."

- Keep a notebook. You’ll want to write down Xavier’s quotes about the world. They’re scary-accurate even decades later.

- Research "Sumud." This is the Palestinian concept of "steadfastness." It’s the invisible engine behind the whole book.

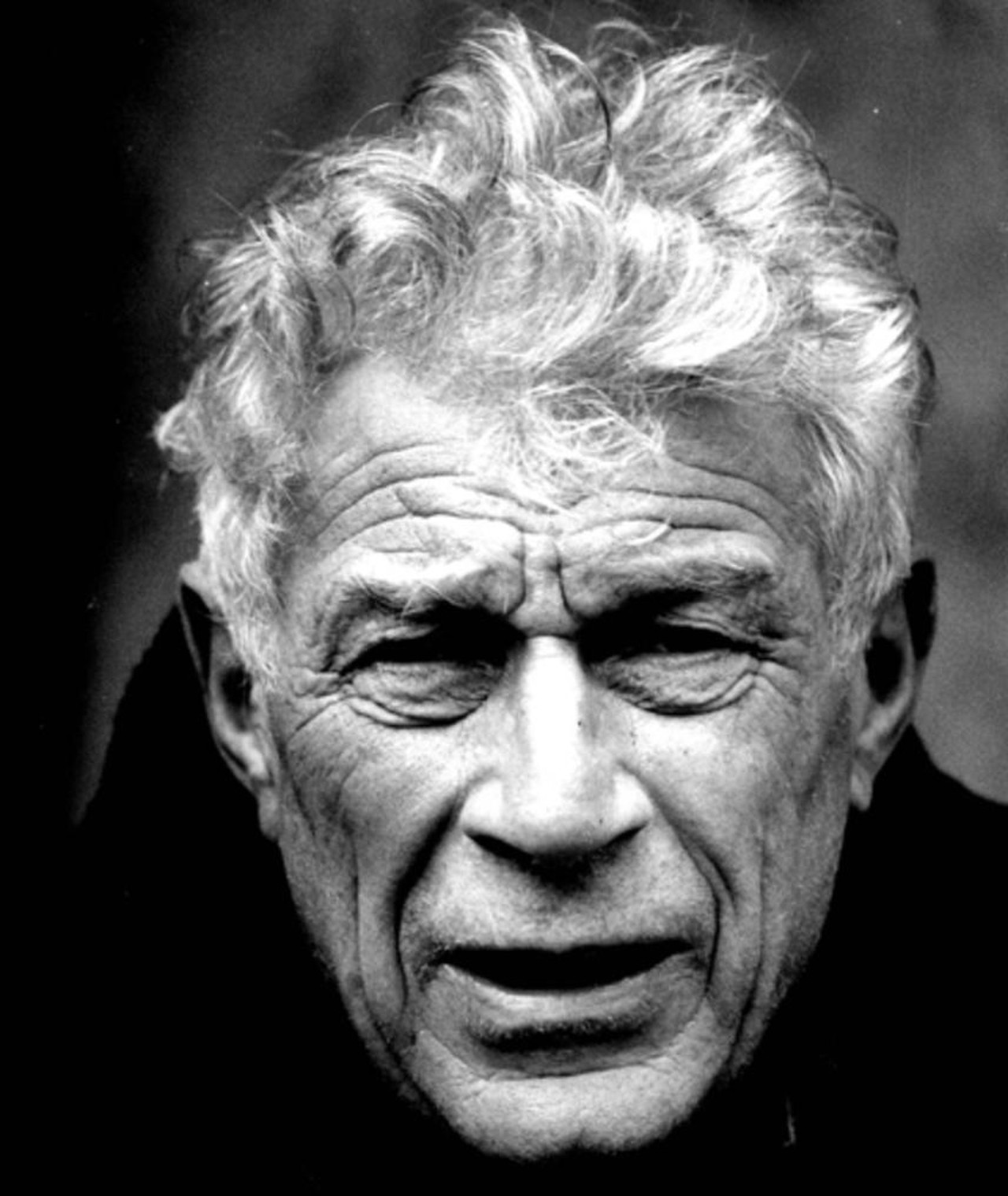

Berger passed away in 2017, but his voice in this novel feels more relevant than ever. He didn't write for the elite. He wrote for the people in the "ramshackle" towns who refuse to give up.

If you want to understand the soul of resistance, start with A’ida’s first letter. It’s waiting for you.