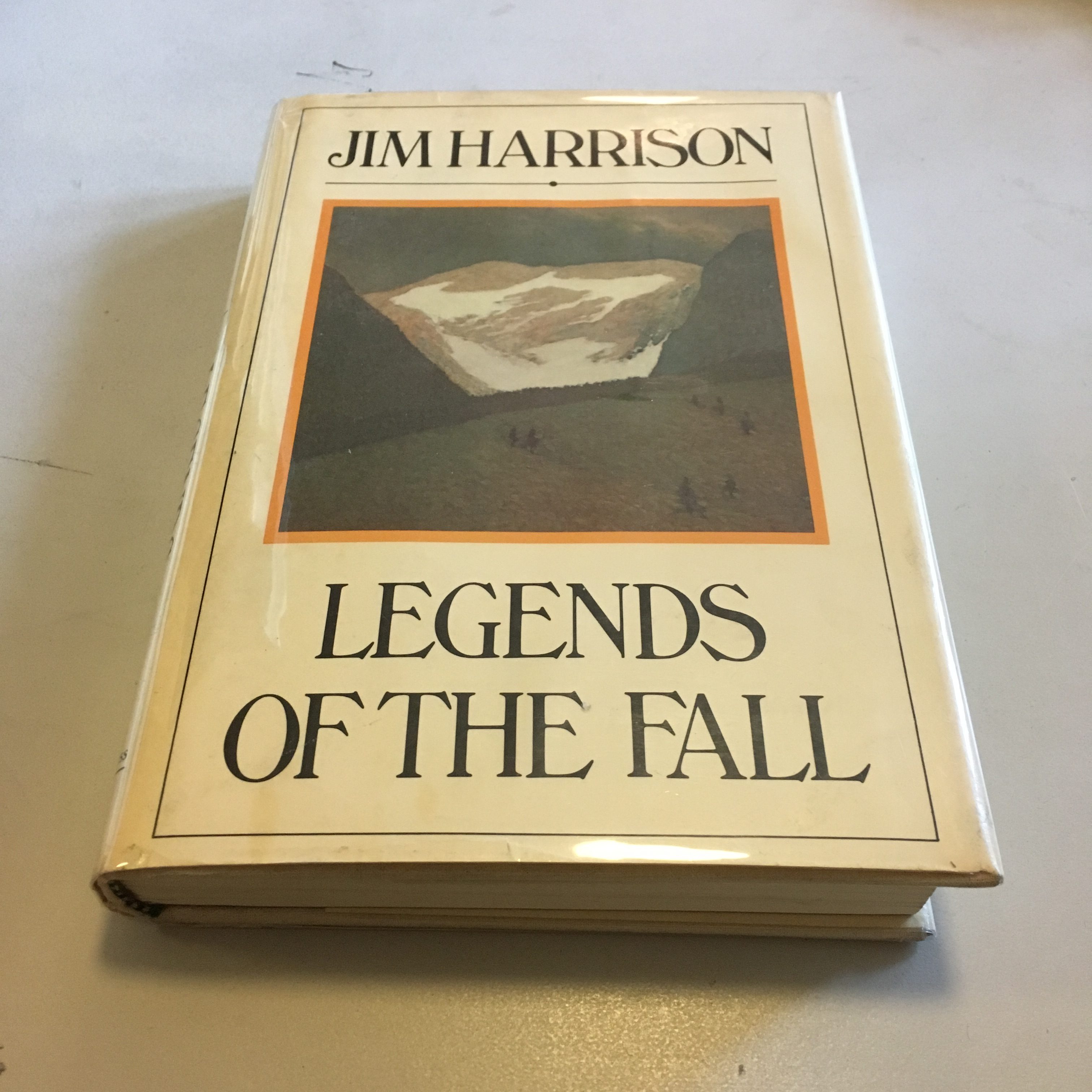

People usually think of Brad Pitt’s flowing hair when they hear the name. They think of sweeping Montana sunsets and a soundtrack that makes you want to weep into a glass of whiskey. Honestly, though? The movie is just a polite suggestion of what Jim Harrison actually put on paper.

Jim Harrison wrote Legends of the Fall in nine days. Nine. He claimed he didn't even revise it, just changed one word and called it a day. It’s a slim novella, barely eighty pages in most editions, but it feels like it weighs ten pounds. It's dense. It’s violent. It doesn’t care about your feelings or your need for a happy ending.

If you've only seen the Edward Zwick film, you're missing the weird, dark, and deeply philosophical heart of why Jim Harrison became a legend himself. The book isn't just a Western; it's a fever dream about how history and bloodline eventually break everyone they touch.

The Montana Eden That Never Was

The story starts in 1914. We meet the Ludlows: three brothers—Alfred, Tristan, and Samuel—living on a remote ranch. Their father, William Ludlow, is a man who saw enough of the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans to decide he wanted absolutely nothing to do with "civilization" ever again.

He builds a fortress of solitude in the Montana wilderness. But you can't outrun the world. Not really.

When Samuel, the youngest and most idealistic, decides to go fight in World War I, the dominoes start falling. Tristan follows to protect him. Alfred follows because he's the responsible one. It’s a classic setup, but Harrison handles it with a kind of detached, almost biblical coldness.

Tristan is the center of the storm. He’s not a hero in the way we usually talk about them. He’s a "natural" man, someone who hears a different frequency than the rest of us. In the book, his grief over Samuel’s death isn't just crying in the rain. It’s a literal descent into madness where he starts scalping German soldiers and carrying their hearts around.

The movie softens this. Hollywood has to. But Harrison’s Tristan is a force of nature, and nature is often cruel.

✨ Don't miss: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

Why Jim Harrison Legends of the Fall Works Better on the Page

There’s a specific rhythm to Harrison’s prose that you just can’t film. He uses long, rambling sentences that feel like a river in flood stage. Then he hits you with a three-word punch to the gut. It’s disorienting. It’s beautiful.

Basically, the novella is about the "Fall" in every sense. The fall from grace. The fall of a family. The literal season.

The Real William Ludlow

Interestingly, the character of William Ludlow was based on a real person, though Harrison’s daughter, Jamie Potts, later revealed there was a bit of a "mistake" in the family lore. Jim believed his ancestor had been with Custer at the Black Hills and told the General the land should stay with the Sioux.

It turns out that was a different William Ludlow. But for the sake of the story, it doesn't matter. The fictional Ludlow carries that weight of American guilt. He is a man trying to wash the blood off his hands by staying in the mountains, only to watch his sons go and find more blood in Europe.

Susannah and the Curse of Choice

In the film, Julia Ormond’s Susannah is a tragic figure trapped between brothers. In the book, she’s even more of a ghost. Harrison doesn't give her as much dialogue because the story is told through a distant, third-person perspective that feels like a history book written by a poet.

Her descent into madness isn't "shown" in the way a screenwriter would do it. Harrison just tells us it happened. It’s a brutal way to treat a character, but it fits the theme: the Ludlow men are a gravity well, and anyone who gets too close gets crushed.

The Differences That Actually Matter

Most people don't realize Legends of the Fall was originally published as part of a trilogy of novellas in 1979. The other two stories, Revenge and The Man Who Gave Up His Name, are just as intense.

🔗 Read more: Black Bear by Andrew Belle: Why This Song Still Hits So Hard

In the novella, the timeline is massive. It covers decades in the blink of an eye.

- The War: Samuel doesn't just die; he is obliterated. Tristan’s reaction is more animalistic than the movie portrays.

- The Mother: In the movie, she’s just gone. In the book, she’s alive and living a bohemian life in the East, occasionally sending letters that no one really knows what to do with.

- The Ending: The movie ends with that iconic bear fight. The book has it too, but it feels less like a grand finale and more like a foregone conclusion. Tristan was always going to die that way. He belonged to the woods.

Harrison’s writing is "clipped and free of waffle," as some critics put it. He doesn't waste time on small talk. The novella is 97% description and 3% dialogue. That’s why the movie feels so different—the filmmakers had to invent a lot of talking to fill the space.

The Jack Nicholson Connection

Here is a bit of trivia that explains a lot about the book's grit. Jim Harrison was flat broke when he wrote this. His friend, the actor Jack Nicholson, heard about his financial trouble and sent him $30,000.

That money bought Harrison the time to sit down and bleed these stories onto the page. Without Nicholson’s "grant," one of the most important pieces of 20th-century American literature might never have existed.

Harrison later said the story felt like "taking dictation" from his own subconscious. He wasn't trying to write a bestseller. He was trying to figure out why men are the way they are—violent, loyal, and ultimately destined to return to the earth.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Story

It’s easy to categorize this as a "manly" book. It’s full of hunting, fishing, war, and whiskey. But if you read it closely, it’s actually a critique of that very "machismo."

Tristan is a "legend," sure, but look at the cost. Everyone he loves dies. His father is paralyzed by a stroke. His wife is killed by a stray bullet from a corrupt cop. His sister-in-law/lover kills herself.

💡 You might also like: Billie Eilish Therefore I Am Explained: The Philosophy Behind the Mall Raid

Harrison isn't celebrating Tristan; he’s observing him like a dangerous predator in a zoo. The "Fall" isn't glorious. It’s a slow, painful rot. The book asks a hard question: Is being "true to your nature" worth the wreckage you leave behind?

How to Approach the Novella Today

If you're going to pick up Jim Harrison Legends of the Fall, don't expect a romance novel. Expect a punch in the mouth.

It’s a story that demands you pay attention to the landscape. Harrison spent his life in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the mountains of Montana. He knew the names of the birds. He knew how the light looked at 4:00 PM in October. That grounded reality makes the operatic violence of the plot feel real instead of cheesy.

Honestly, the best way to read it is in one sitting. It's short enough. Let the rhythm of the sentences get under your skin. Don't worry if you don't "like" Tristan. You aren't supposed to. You're just supposed to witness him.

Next Steps for the Interested Reader:

If the raw, unpolished world of Harrison appeals to you, start by finding the original 1979 trilogy edition. Don't just read the title story. Read Revenge immediately afterward; it’s a masterclass in how to write a thriller without the tropes.

You should also look into Harrison's poetry, specifically Dead Man's Float. It shows the softer side of the man who wrote about scalping and bear fights. Finally, if you want more of the Ludlow-style family saga but with more "meat" on the bones, check out Harrison’s later novel Dalva. It deals with many of the same themes—the West, bloodlines, and the ghosts of the past—but with a much wider lens.