You’ve probably seen it on a bumper sticker or carved into an old church wall: IHS. It looks like a secret code, or maybe a weird acronym. Honestly, it’s just the first three letters of the Jesus name in Greek. People get into heated debates over this stuff. Some say the name "Jesus" is a mistranslation or even a pagan invention. Others claim you have to say it in Hebrew or you're doing it wrong.

The reality is much more interesting.

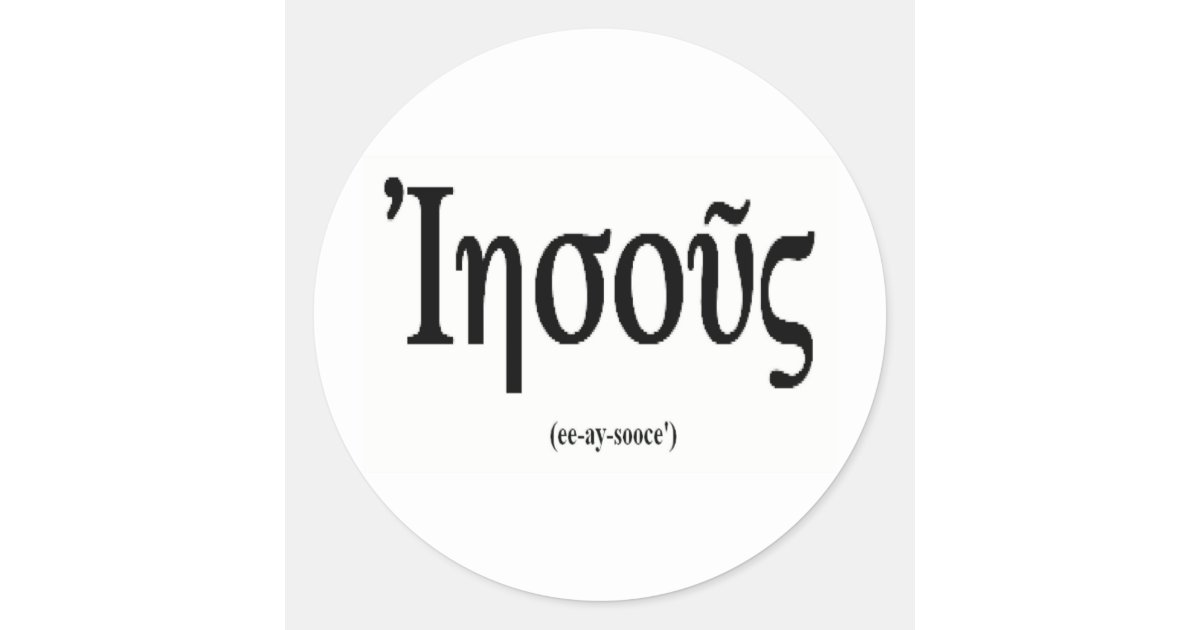

When you look at the New Testament, it wasn't written in Hebrew. It wasn't written in English, obviously. It was written in Koine Greek, the "common" language of the streets in the first century. So, if you want to know what the apostles actually called him when they sat down to write their letters, you have to look at Iēsous.

The linguistic bridge from Yeshua to Iesous

Language is messy. It’s never a clean 1:1 swap.

When the Greek writers of the Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—needed to write down the name of the man they followed, they had a problem. The name was Hebrew: Yeshua. But Greek doesn't have a "sh" sound. It just doesn't exist in their alphabet. If you try to say Yeshua to a Greek speaker back then, they’d struggle with that middle sound.

So, they adapted.

They used the Greek letter Sigma ($\sigma$) to replace the "sh" sound. Then they had to deal with the ending. In Greek, male names usually need to end in a nominative case marker, often an "s" ($\varsigma$). Without it, the name sounds "foreign" or indeclinable to a Greek ear. By the time they were done tweaking it to fit the rules of their grammar, Yeshua became Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous).

It wasn't a conspiracy. It was just how translation worked in a bustling, multicultural Roman Empire.

Why the "J" is a newcomer

Here is a fun fact: the letter "J" didn't even exist until about 500 years ago.

If you had a Bible in the year 1400, you wouldn't see the word "Jesus." You’d see Iesus. The "J" sound is a relatively recent development in the English language, evolving out of the "I" and "Y" sounds. So, when people argue that the Jesus name in Greek is "wrong" because it doesn't sound like the English version, they’re actually looking at the timeline backward.

The Greek version is much, much older.

The Gematria and the Number 888

Greek is a cool language because every letter is also a number. There weren't separate symbols for 1, 2, and 3 back then. Alpha is 1, Beta is 2, and so on. This led to a practice called gematria, where people would add up the numerical value of names to find "hidden" meanings.

Early Christians were obsessed with this.

When you take the Jesus name in Greek—$\text{Iota} (10)$, $\text{Eta} (8)$, $\text{Sigma} (200)$, $\text{Omicron} (70)$, $\text{Upsilon} (400)$, $\text{Sigma} (200)$—and add it all up, you get a very specific number.

888.

For the early church, this was a massive deal. In Christian symbolism, 7 is the number of perfection or completion (the seven days of creation). Therefore, 8 represents a "new beginning" or the "eighth day"—the day of Resurrection. By having a name that added up to 888, it was seen as a divine sign that Jesus was the ultimate new beginning.

Compare that to the "Number of the Beast" in Revelation, which is 666. The contrast was intentional. 666 falls short of perfection (777) at every turn, while 888 explodes past it.

Is Iesous actually related to Zeus?

I hear this one a lot on the internet.

There's a popular conspiracy theory claiming that the Jesus name in Greek was created to honor the Greek god Zeus. The argument usually points to the "ous" ending and says it sounds like "Zeus."

It’s a linguistic nightmare. Honestly, it's just plain wrong.

First off, the "ous" ending in Greek is a standard masculine singular termination. Thousands of Greek words end that way. It’s like saying every English word ending in "son" (like Jackson or Madison) is a secret tribute to the Sun. It’s a huge reach.

Secondly, the name Zeus in Greek is actually Zeus ($\text{Ζεύς}$), but its root is Di- (as in Dios). The phonetics don't even match up when you look at the actual Greek spelling. The name Iēsous had been used in the Septuagint—the Greek translation of the Old Testament—to refer to Joshua for nearly 200 years before Jesus was even born.

The translators of the Septuagint weren't trying to sneak Zeus into the Hebrew scriptures. They were just trying to make the name Yehoshua pronounceable for people living in Alexandria.

The "Joshua" Connection

If you were walking through the streets of Jerusalem in 30 AD and shouted "Iesous," would anyone turn around?

Probably.

But they would have heard "Joshua." In the first century, the Jesus name in Greek was the exact same name as the famous leader who led the Israelites into the Promised Land.

🔗 Read more: Why braids with human hair curls are better than the synthetic version and how to stop them from matting

In the Greek New Testament, when it mentions Joshua from the Old Testament (like in Acts 7:45 or Hebrews 4:8), the text literally uses the word Ἰησοῦς. It’s the same name. It wasn't until much later that English translators decided to use "Joshua" for the Old Testament guy and "Jesus" for the New Testament guy to help readers tell them apart.

It’s a bit like having two friends named "Robert," but you call one "Rob" and the other "Bob" so you don't get confused.

Why this matters for the meaning

The name Yeshua (and thus Iēsous) has a very specific meaning: "YHWH is salvation" or "The Lord saves."

When the angel tells Joseph in the Gospel of Matthew to name the baby Jesus "because he will save his people from their sins," it’s a wordplay. If the name didn't mean "salvation," the sentence wouldn't make any sense. The Greek writers kept this meaning intact by using the most accurate phonetic equivalent available to them.

The Sacred Names: Nomina Sacra

Early Christians had a unique way of writing the Jesus name in Greek in their manuscripts. They didn't always write it out fully.

Instead, they used what we call Nomina Sacra (Sacred Names). They would write the first and last letters of the name and put a horizontal line over the top. So, Iēsous became ΙΣ.

This wasn't because they were lazy.

It was a way of showing extreme reverence. By shortening the name and marking it with a line, they were signaling to the reader: "This word is holy." You find this in the oldest scraps of papyrus we have, like the P52 fragment or the Codex Sinaiticus. It shows that almost immediately, the Greek-speaking church viewed this specific name as something set apart from common language.

Does it matter which name you use?

Some folks get really stressed about this. They worry that if they don't use the "original" Hebrew Yeshua, their prayers won't count.

But look at the history.

The apostles themselves—who were Jewish!—chose to use the Jesus name in Greek when they traveled to places like Ephesus, Corinth, and Rome. They weren't legalistic about the phonetics. They believed the power was in the person, not the specific vibration of the vocal cords.

If Peter and Paul were okay with the Greek translation, it’s probably safe for us too.

Language changes. Symbols evolve. But the core identity stays the same. Whether you say Yeshua, Iēsous, Iesus, or Jesus, you’re pointing to the same historical figure. The Greek version just happens to be the one that helped the message spread across the ancient world.

Actionable Insights for Further Study

To really get a handle on this, you don't need to be a scholar. Here are a few ways to see the Jesus name in Greek for yourself without needing a degree in linguistics:

- Check a Strong’s Concordance: Look up "Jesus" in the New Testament. You’ll see the number G2424. This is the entry for Iēsous. It’ll show you every single time the name appears in the Greek text and how it’s used in different grammatical cases (like Iēsou or Iēsoun).

- Look at an Interlinear Bible: Use a site like Bible Hub to view the Greek and English side-by-side. You can see how the Greek word flows within the sentence structure. It’s a great way to spot the Nomina Sacra in digitized manuscripts.

- Explore the Septuagint (LXX): Find a copy of the Greek Old Testament and look at the book of Joshua. Seeing "Iēsous" used for a Hebrew hero two centuries before the New Testament was written is the best way to debunk the "Zeus" conspiracy theories once and for all.

- Compare the "IHS" Monogram: The next time you're in an old cathedral, look for those three letters. Remember they are the Greek letters Iota, Eta, and Sigma—the first three letters of the name that changed the world.