You’d think after two thousand years, we’d have a clear, singular handle on the guy. But if you actually sit down and read through the different accounts of Jesus in Bible books, you quickly realize you aren't looking at a flat, one-dimensional character. You’re looking at a prism.

Different authors had different agendas.

That’s not a conspiracy theory, by the way. It’s just how writing works. If you ask four people to describe a wedding, the mother of the bride talks about the flowers, the groom talks about his nerves, the photographer talks about the light, and the cynical cousin talks about the open bar. They’re all talking about the same event, but the "truth" feels different depending on who’s holding the pen. When we talk about Jesus in the New Testament, we’re dealing with that exact same human dynamic, scaled up to a cosmic level.

The Four-Way Split: Why the Gospels Don't Match

Most people assume the first four books—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—are just carbon copies of each other. They aren't. Not even close.

Mark is the "action movie" version. It’s short. It’s punchy. He uses the word "immediately" (Greek: euthys) about 40 times. Jesus is constantly on the move, rushing from one miracle to the next, and—interestingly—he’s kinda secretive about it. Scholars call this the "Messianic Secret." He heals someone and then basically tells them, "Don't tell anyone." It’s a fast-paced, breathless account that focuses more on what Jesus did than what he said.

Then you’ve got Matthew. Matthew was writing for a Jewish audience, so he’s obsessed with the Old Testament. He’s constantly dropping "as it was written" or "to fulfill what the prophet said." For Matthew, the story of Jesus in Bible books is the story of the New Moses. That’s why the Sermon on the Mount is such a big deal in his version—it’s Jesus giving a "new law" from a mountain, just like Moses did at Sinai.

Luke is different again. Luke was a doctor (or at least highly educated). His Greek is sophisticated. He’s the guy who focuses on the outcasts. If you’re looking for the Jesus who hangs out with the poor, the women, and the "deplorables" of the first century, Luke is your author. He’s the one who gives us the Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan. It’s a very "social justice" leaning perspective for its time.

The Weirdness of John

Then there’s John. John is the outlier.

While the first three (the Synoptics) share a similar structure, John is doing his own thing. No parables. None. Instead, you get these long, philosophical "I Am" discourses. He starts his book not with a stable or a genealogy, but with the beginning of the universe. In the beginning was the Word. It’s heavy. It’s cosmic. It’s arguably where the most complex theology of Jesus in Bible books originates.

Beyond the "Big Four"

A lot of people stop reading after the Gospels, thinking they’ve got the full picture. Big mistake. If you want to see how the identity of Jesus evolved from a person people walked with to a figure people worshipped, you have to look at the Epistles—the letters mostly written by Paul.

Paul actually wrote most of his stuff before the Gospels were written. Think about that.

The people reading Paul’s letters in the 50s AD didn’t have a leather-bound New Testament. They had letters. In these letters, Jesus isn't just a teacher in Galilee; he’s the "image of the invisible God." In the book of Colossians, Paul argues that Jesus is the literal glue holding the atoms of the universe together. It’s a massive jump from the dusty roads of Nazareth to the throne of creation.

The Problem of the "Historical Jesus"

Let's get real for a second. There is a gap between the "Jesus of Faith" and the "Jesus of History."

Secular historians like Bart Ehrman or the folks from the (now somewhat dated) Jesus Seminar spend their lives trying to peel back the layers of the Bible to find the "real" guy. They look for things that "embarrass" the church—because if a story makes Jesus look bad or confused, it’s more likely to be true. For example, the fact that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist is widely accepted as a historical fact. Why? Because it was awkward for the early church. It made it look like John was superior to Jesus. If they were just making things up, they probably would have left that part out.

When you look for Jesus in Bible books, you have to navigate these tensions:

- The healer vs. the judge.

- The man who gets hungry and tired vs. the God who walks on water.

- The peaceful teacher vs. the guy flipping tables in the Temple.

Jesus in the Book of Hebrews: The High Priest

Hebrews is one of the most underrated books if you’re trying to understand this topic. The author is unknown, but they were clearly a genius at Jewish law. They frame Jesus not as a sacrifice, but as the High Priest who offers himself. It’s a very technical, lawyer-ish argument that bridges the gap between the Old Testament sacrificial system and the New Testament idea of grace. Without Hebrews, our understanding of why Jesus "had to die" (according to Christian theology) would be a lot messier.

Revelation: The Warrior King

If you want to talk about a 180-degree turn, look at the Book of Revelation.

The "Lamb of God" from the Gospels is gone. In his place is a figure with eyes like flaming fire and a sword coming out of his mouth. He’s riding a white horse and leading an army. This is the "apocalyptic Jesus." It’s the version that people often ignore because it’s honestly kind of terrifying. It’s also where a lot of the modern "End Times" obsession comes from. But regardless of your take on the symbolism, it’s a crucial part of the biblical portrait.

Why the Variations Matter

So, why do we have four different Gospels and a bunch of letters that sometimes feel like they’re talking about different people?

Because humans are complex. If you only have one perspective, you have a cult. If you have multiple perspectives that don't always perfectly align, you have a living tradition. The discrepancies in the accounts of Jesus in Bible books—like whether there was one angel at the tomb or two—actually give the text more historical weight to some scholars. It shows they weren't all sitting in a room together "fixing" the story to make it look perfect.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Best Bites on the Coles Bakery and Cafe Menu

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

If you actually want to get a grip on this without just taking someone's word for it, here is how you should actually read it. Don't start at page one and go to the end. That's how people get stuck in Leviticus and give up.

1. Compare the "Passion" narratives side-by-side. Pick a Saturday. Read the crucifixion account in Mark, then immediately read the one in John. Note the differences. In Mark, Jesus is almost silent and seems abandoned. In John, he’s in total control, even speaking to his mother from the cross. Seeing these differences for yourself is better than any commentary.

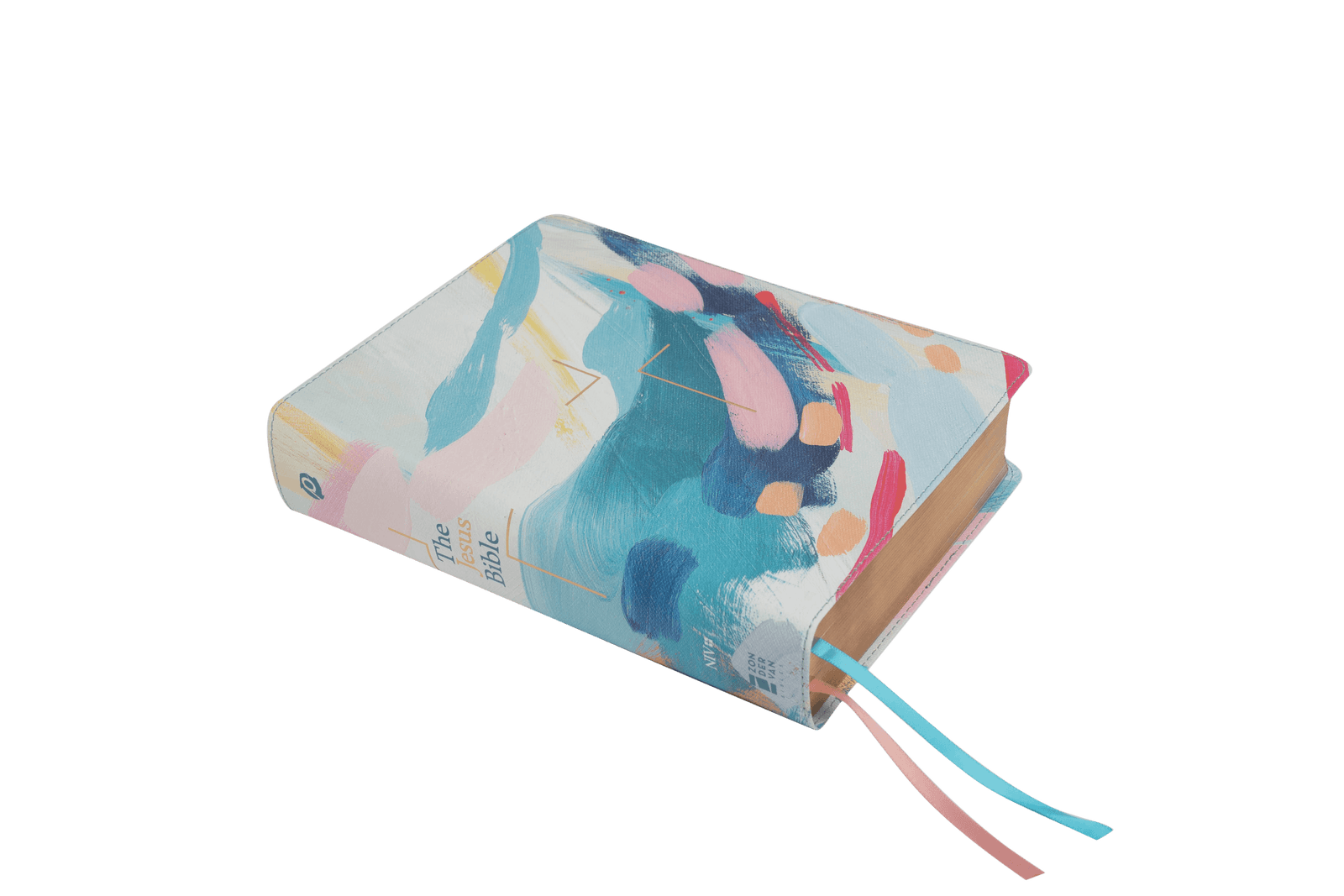

2. Use a "Study Bible" with cross-references. Look for one like the ESV Study Bible or the NRSV HarperCollins. These have notes at the bottom that explain the historical context. When Matthew quotes a prophecy, look up the original verse in Isaiah or Micah. You’ll see how the authors were "re-reading" their own history to make sense of Jesus.

3. Read the "Red Letter" words in isolation. Some Bibles print the words of Jesus in red. Try reading just those for a chapter. It strips away the narrator's bias and lets you look at the raw teaching. You’ll notice how often Jesus answers a question with another question—he was famously annoying to debate.

4. Check out the "Non-Canonical" stuff (for context). To really understand why the Jesus in Bible books looks the way he does, look at what didn't make it in. Read the Gospel of Thomas or the Gospel of Peter. You’ll quickly see why the early church fathers rejected them. They feel... different. Some are too "magical" (like the one where child Jesus makes clay birds and makes them fly) and others are too philosophical. It helps you appreciate the "grounded" nature of the four we actually have.

5. Focus on the audience. Whenever you open a book in the New Testament, ask: "Who was this written for?"

- Matthew: Jewish traditionalists.

- Mark: Roman Christians under pressure.

- Luke: Educated Greeks/Gentiles.

- John: A community seeking deep spiritual identity.

Understanding the "who" explains the "why" behind the specific way Jesus is portrayed. You’ll stop looking for a contradiction and start seeing a specific message tailored for a specific group of people struggling to make sense of a man who changed everything.