You’re staring at a blank screen or a messy prototype, wondering why your game feels "off." It’s a common wall. Most people think game design is about coding or drawing or knowing how to balance a spreadsheet, but they’re wrong. Honestly, those are just tools. The real work happens in the player's mind. That’s the core premise of The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell.

Schell isn't just some academic. He worked at Disney Imagineering and teaches at Carnegie Mellon. He knows that games are weird, psychological puzzles. He wrote this book because there isn't one single "formula" for a hit. Instead, there are dozens of ways to look at your work—what he calls "lenses."

If you haven't cracked this book open yet, you're essentially trying to paint a masterpiece in the dark.

Why We Keep Coming Back to the Lenses

Most design books get dated fast. They talk about Facebook games from 2010 or specific hardware that doesn't exist anymore. Schell’s work is different. It’s evergreen because it focuses on human behavior, which hasn't changed much in a few thousand years.

Take the "Lens of the Elemental Tetrad." It sounds fancy, but it’s basically a reality check for your project. Are your mechanics, story, aesthetics, and technology actually working together, or is the story just a thin layer of paint on a boring mechanic? I’ve seen countless indie devs spend six months on a lighting engine while their core "jump" mechanic feels like lead. The Tetrad forces you to see the imbalance.

The Problem With "Fun"

Fun is a terrible word for designers. It’s too vague.

Schell argues that we need to stop chasing "fun" and start chasing "experience." When you play The Last of Us, is it "fun" to hide from a clicker while your heart hammers in your throat? Not really. It’s stressful. It’s tense. But it is a powerful experience.

The book gives you the "Lens of the Player" to help you get out of your own head. You aren't the player. You know where all the secrets are. You know how the boss behaves. You're biased. By using these lenses, you’re forced to step into the shoes of someone who has no idea what’s going on.

👉 See also: Will My Computer Play It? What People Get Wrong About System Requirements

The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses and the Psychology of Flow

If you've ever looked into game theory, you've heard of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of "Flow." It’s that state where you lose track of time because the challenge perfectly matches your skill. Schell spends a good chunk of time explaining how to stay in that zone.

Too hard? The player gets frustrated and quits.

Too easy? They get bored and check their phone.

It’s a tightrope. The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses offers specific questions to ask yourself to find that sweet spot. One of my favorites is the "Lens of Endogenous Value." Basically, why does the player care about that gold coin? If the coin doesn't help them survive or show off or unlock something cool, it’s just a yellow circle. It has no value.

It's Not Just for Video Games

Here is something people miss: this book is just as relevant for board games, escape rooms, or even a weird scavenger hunt you’re planning for a birthday party.

The principles of curiosity, feedback loops, and conflict are universal. Schell draws from architecture, music, and theater. He understands that a game is just a structured way to play, and play is a fundamental human need.

Stop Polishing the Wrong Things

One of the biggest traps in the industry is "creeping featurism." You think, if I just add a crafting system, the game will be better. Then you add a fishing minigame. Then a skill tree.

Suddenly, you have a bloated mess.

✨ Don't miss: First Name in Country Crossword: Why These Clues Trip You Up

The "Lens of Economy" and the "Lens of Simplicity" act like a pair of garden shears. They help you prune the junk. A great game isn't defined by how much stuff is in it, but by how well the core elements interact. Think about Tetris. It has one mechanic. One. And it’s arguably the most perfect game ever made.

The Hidden Power of Iteration

Schell is obsessed with iteration. He says the more times you fail and fix, the better your game gets. It’s a simple math problem. If you iterate twice, your game might be okay. If you iterate fifty times, it’ll be great.

This requires killing your darlings. You might love your complex magic system, but if players find it confusing during a playtest, it has to go. Or it has to change. The book gives you the "Lens of the Toy," which asks: is the mechanic fun to play with even without a goal? If moving your character feels good—like the swing in Spider-Man or the jump in Mario—you’re halfway there.

Dealing With the "Designer's Ego"

We all have it. We want to be the "auteur" with the brilliant vision. But Schell constantly reminds us that the game doesn't exist on the disc or in the code. It exists in the space between the screen and the player's brain.

If the player doesn't "get it," it’s your fault. Not theirs.

Using the "Lens of Helpfulness" or the "Lens of Freedom" helps you realize where you might be suffocating the player with tutorials or railroading them into a story they don't care about. It's humbling. It’s also the only way to get better.

Real-World Application: The Deck of Lenses

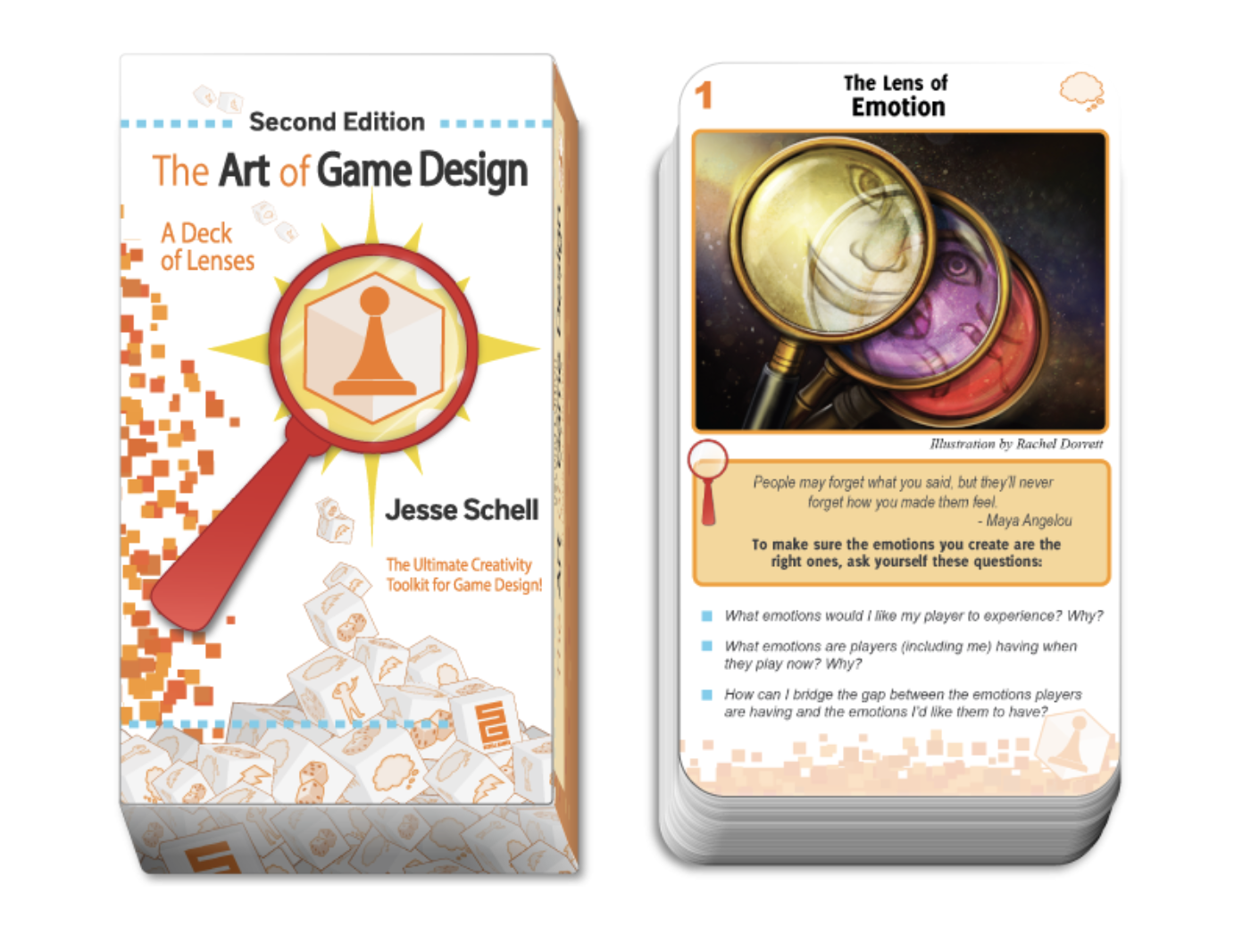

If you’re serious about this, don’t just read the book. Schell actually released a physical deck of cards. Each card has a lens and a few pointed questions.

🔗 Read more: The Dawn of the Brave Story Most Players Miss

I’ve seen pro teams at places like Riot or Blizzard pull these cards during brainstorms. When a project is stuck, they’ll literally draw a card—maybe the "Lens of Beauty"—and ask, "How can our game be more beautiful in a way that reinforces the gameplay?" It sounds cheesy until you see it work. It breaks the "groupthink" that happens in every studio.

Beyond the Mechanics

The later chapters of the book dive into the business side and the soul of the work. It covers things like team dynamics, pitching your idea, and why we even make games in the first place.

Games can be transformational. They can teach empathy. They can improve spatial reasoning. Or they can just provide a much-needed escape from a crappy day. Schell never loses sight of the "why."

Putting the Lenses to Work Today

You don't need to memorize all 100+ lenses at once. That’s a recipe for a headache. Instead, use them as a diagnostic tool.

- Identify the Symptom: Is your game boring? Frustrating? Too short?

- Find the Right Lens: If it's boring, look at the "Lens of Challenge" or the "Lens of Surprise."

- Ask the Hard Questions: The book provides 3–5 questions for every lens. Answer them honestly. If the answer is "I don't know," that’s where you start working.

- Prototype the Solution: Don’t build the whole thing. Just build a "grey box" version to see if the change actually fixes the problem.

Game design is a craft, not a magic trick. It takes discipline to look at your work objectively. Jesse Schell’s The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses provides the framework to do exactly that. It turns the "I hope people like this" anxiety into a structured process of "I know why this works."

If you want to move from being someone who "has a great idea for a game" to someone who actually builds great games, start by changing how you look at the screen. Pick one lens today. Apply it to the last game you played. Then apply it to the one you're making. The difference in clarity is usually immediate.