Music history is messy. Honestly, if you dig into the roots of early jazz and blues, you aren't just looking at sheet music; you’re looking at a raw, often uncomfortable reflection of American culture at the turn of the century. When people bring up jelly roll blues facial abuse, they’re usually swirling together a cocktail of historical performance practices, the lyrics of Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton, and the aggressive physical comedy of the vaudeville era. It's a heavy topic. It’s also one that gets wildly misinterpreted by folks looking at the past through a 2026 lens without understanding the brutal reality of the 1910s stage.

Morton published "Original Jelly Roll Blues" in 1915. It was a landmark. It’s often cited as the first published jazz composition, a moment where the improvisational chaos of New Orleans finally hit paper. but the "blues" part of the title and the "facial abuse" part of the conversation usually stem from the way these songs were performed in minstrelsy and tent shows.

The Gritty Reality of Early Jazz Performance

Vaudeville was physical. You’ve gotta understand that performers didn't just sit and play; they contorted. They masked. In the context of the early 20th century, "facial abuse" refers to the extreme, often degrading facial contortions and "mugging" that Black performers were forced to do to satisfy white audiences. This wasn't just "expression." It was a survival tactic and a performance requirement that many modern historians, like those at the Smithsonian, point to as a form of psychological and professional trauma.

When we talk about jelly roll blues facial abuse, we are talking about the intersection of a brilliant musical composition and the dehumanizing "clowning" expected of the musicians who played it.

Morton himself was a complicated guy. He was a Creole of color who often looked down on the very "blues" elements he helped codify. He was a pool shark, a pimp, and a braggart. He claimed he invented jazz. He didn't, obviously, but he was its first great architect. Yet, even a man with his ego had to navigate a world where his face—his expressions—were often treated as a commodity for mockery.

Why the "Facial Abuse" Narrative Persists

Why are we still talking about this? Well, the "blues" in the title isn't just a musical scale. It’s a state of being.

There's a common misconception that the term refers to actual physical violence mentioned in the lyrics. If you look at the 1915 lyrics, you won't find a play-by-play of a fight. Instead, you find a rhythmic boast. However, the performance of the blues often involved "blue notes" and "blue faces"—a term sometimes used for the exaggerated expressions of sorrow or joy that were pushed to a grotesque limit.

📖 Related: Emily Piggford Movies and TV Shows: Why You Recognize That Face

- The physical strain of the "shout" singing style.

- The requirement for Black musicians to maintain a "permanent grin" or a "comical pout."

- The literal exhaustion of playing 12-hour shifts in the District (Storyville).

It's exhausting just thinking about it. Imagine playing "Jelly Roll Blues" while being required to look like a caricature. That's the real abuse. It’s systemic. It’s baked into the era.

Historical Context: 1915 vs. Now

Let's get specific. In the early 1900s, the "theatrical mug" was a specific skill. Performers like Bert Williams—who Morton certainly knew of—had to use burnt cork and perform facial "gymnastics." This history of jelly roll blues facial abuse is essentially the history of the "mask" that Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote about.

"We wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes..."

Morton’s music was sophisticated. It had "Spanish tinge." It had complex stop-time breaks. But the industry he worked in was anything but sophisticated. It was a meat grinder. When researchers discuss the "abuse" of the era, they’re looking at the physical toll on the body. Piano players like Morton developed repetitive strain, yes, but the "facial" aspect refers to the loss of dignity in the performance of the "blues."

Understanding the Lyrics and the Vibe

The lyrics of the "Original Jelly Roll Blues" talk about a "wayward boy" and the "jelly roll" itself—which, let's be real, was a double entendre for sex.

"I heard a lady say, 'Give me that jelly roll!'"

👉 See also: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

It’s playful. It’s ribald. But the "blues" part of the title allowed the music to be marketed to a specific demographic that expected a certain "look" from the performer. If you weren't "making faces," you weren't "playing the blues" in the eyes of the booking agents.

Debunking the Myths

Some internet rumors suggest jelly roll blues facial abuse refers to a specific incident where Morton was attacked. There is no historical record of a "facial abuse" incident involving Morton and this specific song. He got into plenty of scrapes—he was stabbed in the head once in a dispute over a woman—but "facial abuse" as a specific term is almost always a reference to the performance style or the broader mistreatment of artists in the Jim Crow South.

We also have to look at the "blues" as a genre. It was often called "the devil's music." It was associated with the "low life." Consequently, the people performing it were treated as less than human. The "abuse" was the denial of their artistry in favor of their "entertainment value."

The Legacy of the 1915 Publication

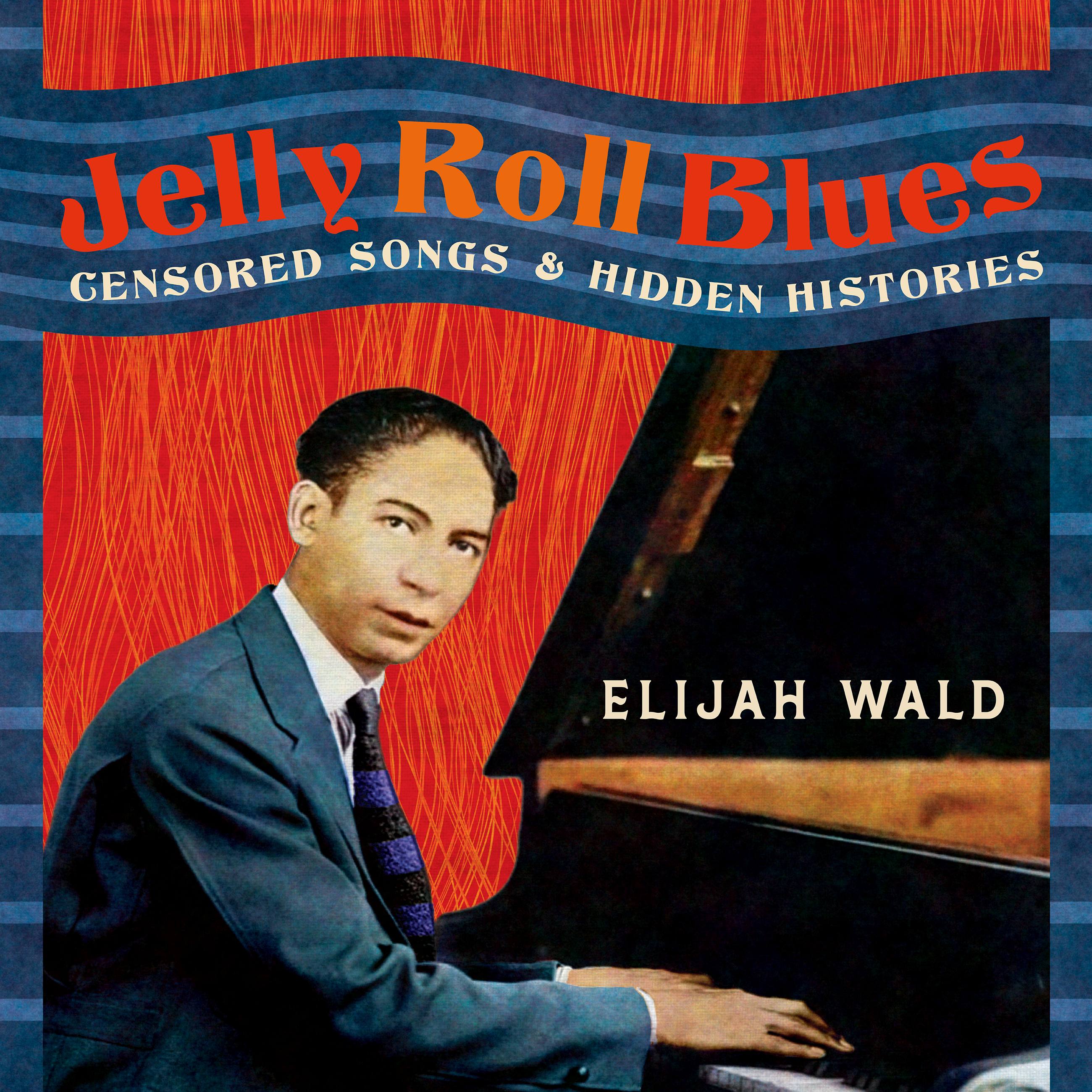

When the Chicago-based publisher Will Rossiter put out the sheet music, he put a caricature on the cover. That’s the "facial abuse" right there in print. A drawing that stripped Morton of his features and replaced them with a stereotype. This is the visual equivalent of the "blues" that the music was trying to transcend.

Morton's "Original Jelly Roll Blues" actually contains instructions. It’s precise. He wanted it played exactly as written. He was fighting against the "abuse" of his music by amateur players who just wanted to "clown" around. He was a serious composer. He was a man who wore a diamond in his tooth so people would know he was successful. He didn't want to be a caricature.

How to Research This Without Falling for AI Hallucinations

If you're looking for more info on this, don't just search for the "abuse" part. Look for:

✨ Don't miss: Ebonie Smith Movies and TV Shows: The Child Star Who Actually Made It Out Okay

- "The physical requirements of minstrelsy."

- "Jelly Roll Morton’s Library of Congress recordings" (where he talks about his life in detail).

- "The iconography of early jazz sheet music."

You'll find that the "abuse" is a theme of the era, not a single event. It’s about the "face" Black music had to put on to be sold.

Actionable Insights for Music Historians and Fans

If you want to truly appreciate the "Jelly Roll Blues" without perpetuating the "facial abuse" of the past, here is how you should approach the history:

- Listen to the 1938 Library of Congress recordings. Alan Lomax sat Morton down at a piano, and Morton told the truth. He talks about the "stinging" nature of the business.

- Analyze the sheet music covers. Compare the 1915 Rossiter cover to the later, more "refined" versions. The shift in how Morton's face is portrayed tells the story of the changing American landscape.

- Study the "Spanish Tinge." Morton argued that if you don't have that "tinge" (a Habanera rhythm), you don't have the right "seasoning" for jazz. This moves the conversation away from "abuse" and toward technical mastery.

- Recognize the difference between "The Blues" and "Minstrelsy." One is an art form born of struggle; the other is a caricature of that struggle. The "facial abuse" occurs when the two are forced together.

The real story isn't a scandalous incident. It’s the story of a man who wrote a masterpiece and had to watch the world try to turn it—and him—into a joke. Understanding jelly roll blues facial abuse means acknowledging the weight that every note of early jazz carried. It wasn't just music; it was a battle for the right to be seen as an artist rather than a prop.

Next time you hear that stomping piano rhythm, remember the face behind it. Not the caricature on the sheet music, but the man who claimed he "invented jazz" because, in a world that tried to abuse his identity, he had to be his own biggest hero.

To further your understanding, look into the works of Lawrence Gushee, who spent years documenting Morton's early life. He clears up much of the "myth-making" that Morton himself started and helps contextualize the brutal environment of the early 20th-century music industry. By focusing on the primary sources—the copyright deposits and the firsthand interviews—you get a much clearer picture of the resilience required to play the blues in 1915.