You’ve seen the maps. Maybe you were scrolling through a museum's digital archive or you caught a glimpse of that massive 2023 retrospective at the Whitney. They look familiar at first—the recognizable outline of the United States—but then everything starts to feel... off. The borders are dripping. There are newspaper clippings about reservation water rights plastered over Kansas. A plastic tomahawk or a Redskins pennant might be dangling from the frame.

This is the world of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith art. And honestly, if you think she’s just painting geography, you’re missing the entire point.

Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, spent over fifty years basically hacking the language of modern art to tell a story that the history books tried to bury. She didn't just "paint"; she waged a kind of visual warfare using collage, satire, and a heavy dose of irony. When she passed away in early 2025 at the age of 85, she left behind a legacy that forced the "fine art" world to finally admit that Native American art wasn't just beadwork and pottery in a glass case. It was, and is, a living, breathing, and often very angry political force.

The "Map" That Isn't a Map

Most people know her for the maps. Specifically, works like State Names Map I or the iconic Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People).

In Trade, she painted a huge, ghost-like canoe across a canvas dripping in blood-red paint. Above it, she hung a clothesline of "trinkets"—sports memorabilia, toy tomahawks, and cheap souvenirs that use Native imagery as a brand. It’s a direct, punch-in-the-gut reference to the lopsided "trades" of the colonial era. She’s essentially asking: You took the land, and this is what you gave us back?

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

But look closer at the "maps" she created throughout the 90s and 2000s. She often turned them on their side or upside down. Why? Because the orientation of a map is a power move. To a Salish person, the land isn't defined by the arbitrary straight lines drawn by 19th-century surveyors in D.C. By dripping paint over the borders of states like Wyoming or Oklahoma, she’s literally erasing the colonial lines and letting the land underneath "breathe" again.

Why the Art World Ignored Her (Until They Couldn't)

It's easy to forget how gatekept the art world used to be. Back in the 70s, when Smith was getting her Master’s at the University of New Mexico, her professors basically told her that she couldn't be an "artist" and "Indian" at the same time. You were either a "traditional" craftsperson or a "modern" painter.

She decided that was nonsense.

She formed the Grey Canyon Group in 1977. It was a collective of Native artists like Emmi Whitehorse and Conrad House who were doing contemporary, abstract work. They weren't making curios for tourists; they were looking at Rauschenberg and Warhol and saying, "We can use these tools too."

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Smith’s style is a wild mix. You’ll see:

- Neo-Expressionist brushstrokes: Think messy, emotional, and textured layers of oil and acrylic.

- Pop Art appropriation: Using things like Mickey Mouse or "Made in the USA" labels to talk about consumerism.

- Indigenous Pictographs: Incorporating ancient symbols of horses, bison, and humans that she researched from petroglyph sites.

She calls herself a "cultural arts worker." That's such a better term than "artist" because it implies a job. Her job was to bridge the gap. She wasn't just making pretty things for a living room; she was documenting a genocide that is, in her view, still ongoing through environmental destruction and cultural erasure.

The Trickster in the Canvas

If you see a coyote in a Jaune Quick-to-See Smith painting, pay attention. In Salish and many other Indigenous cultures, the Coyote is the trickster. He’s smart, he’s a survivor, and he’s often making a mess of things to teach a lesson.

Smith often used the Coyote as an avatar for herself. In Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights, a Coyote stands in a canoe filled with animals and symbols of home (like a small cabin). It’s a flip on the Noah’s Ark story. But here, the "flood" is colonialism, and the Coyote is the one trying to save the stories and the people.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

It’s funny, but it’s the kind of funny that makes you feel a little bit uncomfortable once you realize what’s actually being said. She uses humor as a Trojan horse. You come for the bright colors and the cool collage, and you stay for the realization that the "vanished Indian" myth is a lie.

The 2023 Whitney Milestone

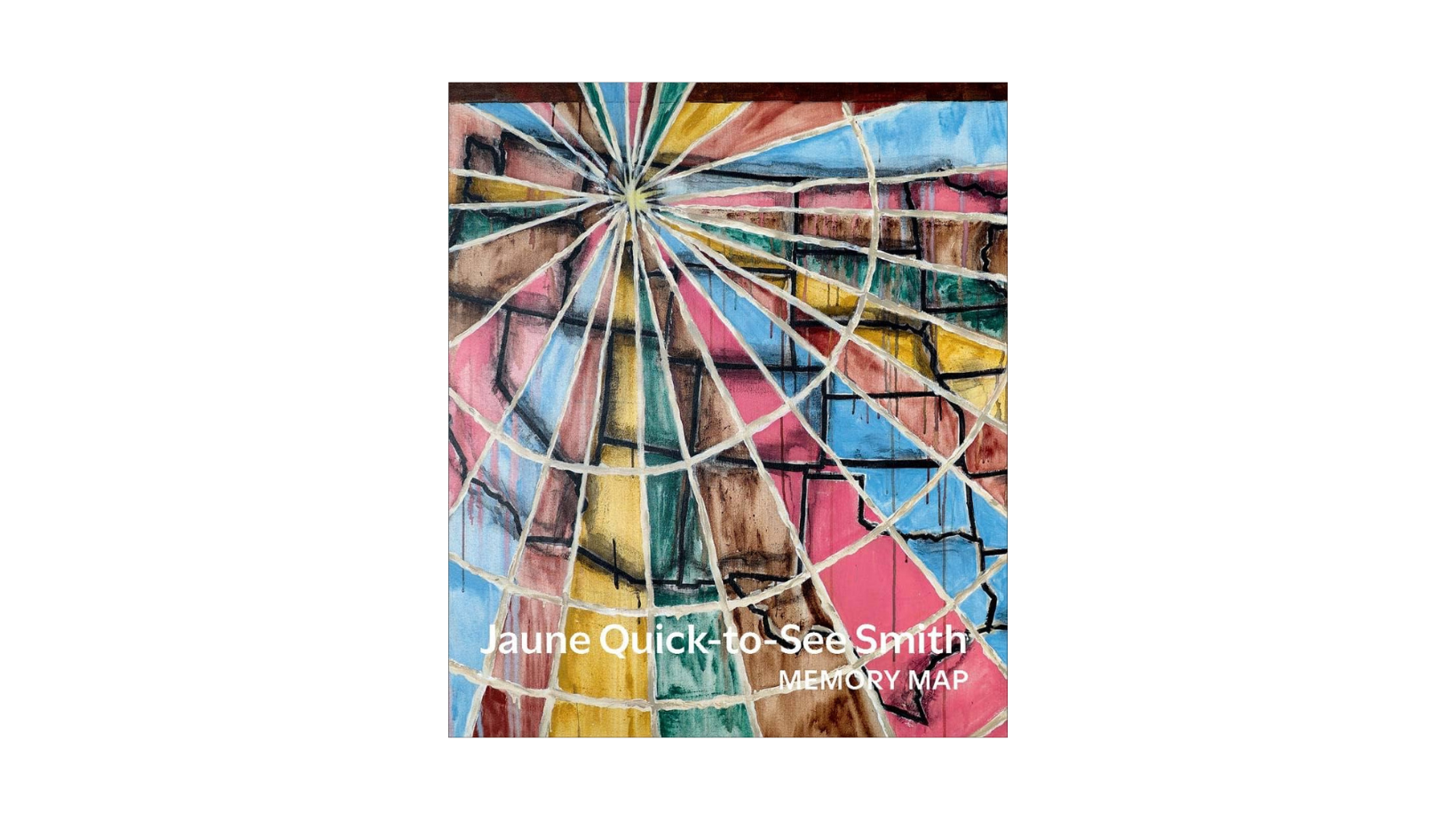

The biggest moment in her career—and maybe in the history of Native American art in the U.S.—was the Memory Map retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2023.

It was the first time the Whitney ever gave a solo retrospective to a Native artist. Think about that for a second. The museum has been around for nearly a century, and it took until 2023 to highlight a Native person this way. Smith didn't just walk through that door; she kicked it down and brought dozens of other Native artists with her. She was a tireless curator, always pushing for younger artists like Nicholas Galanin or Wendy Red Star to get their due.

Actionable Insights: How to Engage with Her Work Today

If you're looking to understand Jaune Quick-to-See Smith art beyond just a Google Search, here is how you actually "read" her pieces:

- Look for the layers: Her work is almost never just one medium. It’s "palimpsest"—layers upon layers. Read the newspaper clippings she hides under the paint. They often contain the real "news" of the piece, like reports on uranium mining on Indigenous lands.

- Identify the "Stolen Symbols": Spot the commercial logos or sports mascots. She’s reclaiming them, stripping them of their marketing power and putting them back into a context of history and theft.

- Notice the lack of a horizon: Smith famously avoids the "Western" horizon line. In her view, the land and sky are connected, not separated by a flat line. This reflects a holistic Native worldview rather than a European "landscape" view where the viewer is standing "outside" the scene.

- Visit the Permanent Collections: You don't have to wait for a special show. Her work is now in the MoMA, the Met, and the Smithsonian. If you're in D.C., go see Target at the National Gallery of Art—it was the first painting by a Native artist they ever bought.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith didn't want to be a "museum piece." She wanted her art to be a diary of survival. When you look at her maps, don't just look for your hometown. Look for the stories that were there before the map was even drawn.

Next Steps for Collectors and Students

- Study the Prints: Smith was a master printmaker. Many of her most biting social commentaries are in her lithographs and monotypes created at the Tamarind Institute.

- Research the Grey Canyon Group: To understand her roots, look into the 1970s movement of Native modernism she helped lead.

- Follow the Legacy: Look at the artists she curated in the "The Land Carries Our Ancestors" exhibition at the National Gallery of Art to see where the movement is headed in 2026 and beyond.