When we talk about the Pacific Theater, the conversation usually pivots immediately to the horrific treatment of Allied prisoners at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Army. We think of the Bataan Death March or the Bridge over the River Kwai. But there is a massive, often awkward silence regarding the other side of that coin: Japanese POWs in WW2.

It’s a complicated subject. Honestly, for decades, it was a subject many Japanese veterans didn't even want to touch. Why? Because in the eyes of the Japanese military code—specifically the Senjunnmon or Code of Military Conduct—surrender wasn't just a defeat. It was a total, irreversible erasure of your humanity.

You weren't supposed to be captured. You were supposed to die.

This cultural backdrop created a surreal dynamic for the thousands of Japanese soldiers who did end up in Allied hands. They were men who technically "didn't exist" anymore to their own government. It’s a story of psychological collapse, unexpected kindness in Australian or American camps, and a very slow, painful road back to a country that had already held their funerals.

The Myth of the "No Surrender" Soldier

History books often paint a picture of every single Japanese soldier being a suicidal zealot. That’s not quite right. While the indoctrination was incredibly intense, the reality on the ground in places like Guadalcanal or Okinawa was more desperate.

A lot of Japanese POWs in WW2 were captured because they were physically incapable of fighting or killing themselves. We’re talking about men ravaged by malaria, beriberi, and literal starvation. By 1944, many units were eating grass and tree bark.

When you’re that weak, you can’t pull a grenade pin.

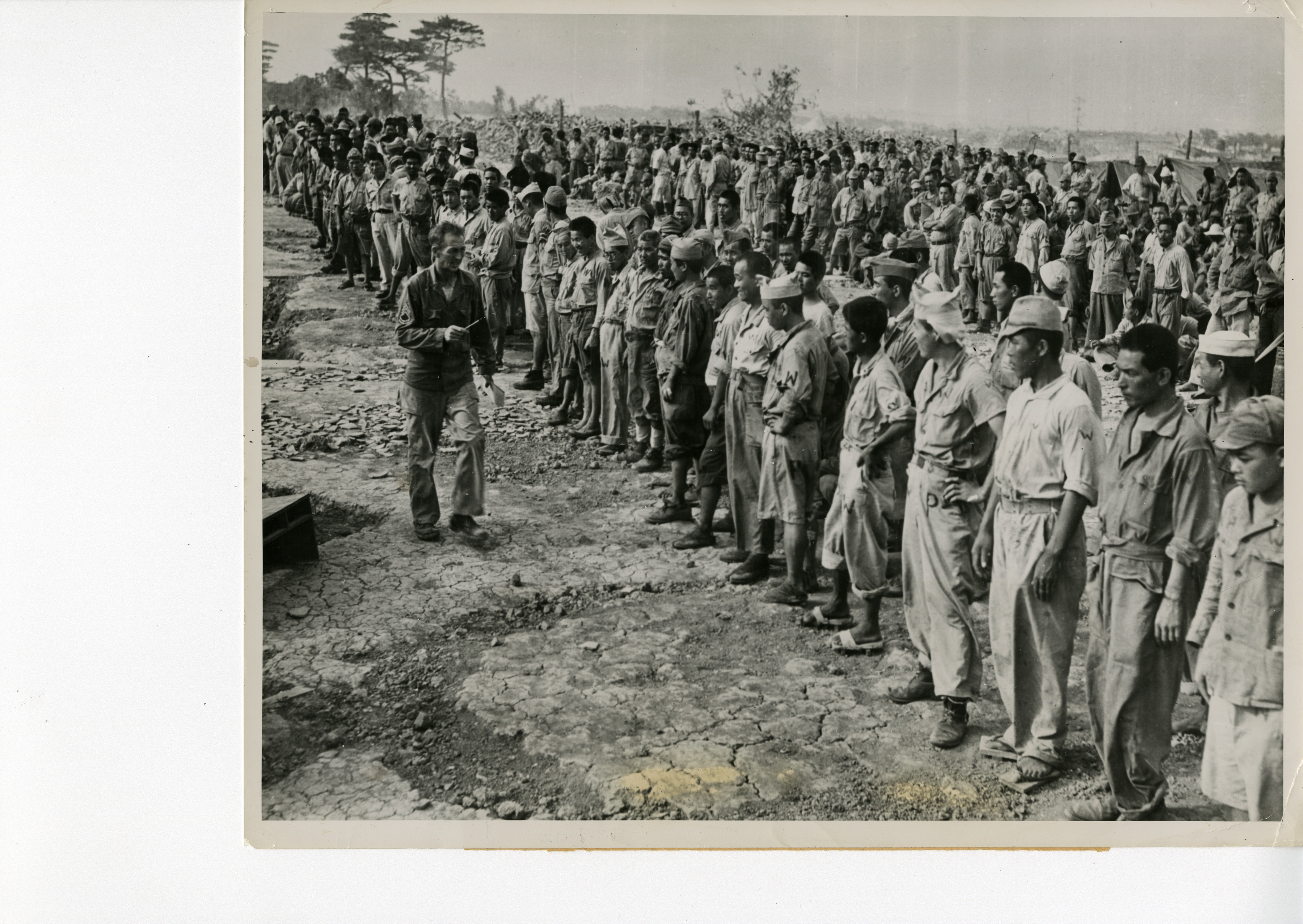

Early in the war, the number of prisoners was tiny. For example, during the entire Battle of Tarawa, only 17 Japanese soldiers were captured alive out of a garrison of nearly 5,000. But as the war dragged on, those numbers started to shift. It wasn't necessarily because the "spirit" of the soldiers broke, but because the sheer scale of the Allied advance made total annihilation impossible to maintain.

One of the weirdest things about these captures was the "cooperativeness" of the prisoners. Intelligence officers like Otis Cary, who grew up in Japan and spoke fluent Japanese, noted something fascinating. Once a Japanese soldier realized he wasn't going to be executed by the Americans—which is what their officers told them would happen—they often became incredibly talkative.

✨ Don't miss: Election Where to Watch: How to Find Real-Time Results Without the Chaos

Since they had never been trained on what to do if captured (because capture was "impossible"), they didn't have a "name, rank, and serial number" protocol. They’d just... talk. They’d draw maps. They’d identify unit locations. They felt that by being captured, their tie to Japan was severed, so they were essentially starting a new life as a blank slate.

The Cowra Breakout: Blood on Australian Soil

You can't talk about Japanese POWs in WW2 without mentioning the Cowra Breakout of 1944. It’s one of those events that feels like a movie script, but it was a bloody, tragic reality.

Cowra was a small town in New South Wales, Australia. It housed a massive POW camp. By August 1944, it held over a thousand Japanese prisoners. Unlike the Italians or Germans in the same camp, who were mostly content to sit out the war and work on local farms, the Japanese were tortured by their own shame.

They felt they had to do something to reclaim their honor.

On the night of August 5, over 1,000 prisoners charged the wire armed with nothing but sharpened mess tin knives and baseball bats. They ran straight into Australian machine-gun fire.

- 231 Japanese soldiers died.

- Many committed suicide or were killed by their comrades to avoid being recaptured.

- 4 Australians were killed.

It was the largest prison breakout of the entire war. But it wasn't a breakout intended for escape. There was nowhere to go in the Australian bush. It was a mass suicide attempt. It highlights the massive psychological gap between Western views of "living to fight another day" and the Imperial Japanese view of "death before dishonor."

Life in the American and Australian Camps

Surprisingly, if you were a Japanese prisoner in a US-run camp like Featherston in New Zealand or McCoy in Wisconsin, your physical life was often better than it had been in the Imperial Army.

The food was better. You had medical care.

🔗 Read more: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

In some camps, prisoners were allowed to organize sports, perform traditional plays, and even publish their own newsletters. The US military realized early on that treating Japanese POWs in WW2 humanely was a massive intelligence win. They used photos of well-fed, healthy prisoners as propaganda, dropping them over Japanese lines to encourage more surrenders.

It worked, but only to a point.

The psychological toll remained. Many prisoners used aliases because they didn't want their families back home to find out they were alive. If the village found out a son was a POW, the family could be ostracized or harassed.

The Soviet Nightmare: Siberia and the "Lost" Men

While the experience in US or Australian camps was generally "civilized" (by war standards), the fate of those captured by the Soviet Union was a different universe of horror.

In August 1945, the USSR invaded Manchuria. They captured roughly 600,000 Japanese soldiers. These men weren't sent to "camps" in the Western sense. They were sent to the Gulags.

They were forced into hard labor in the freezing Siberian tundra.

Estimates suggest that around 60,000 of these Japanese POWs in WW2 died in Soviet captivity. Some weren't repatriated until the 1950s—years after the war ended. When they finally stepped off the boats at Maizuru port, they returned to a Japan that had already rebuilt itself, looking like ghosts from a past everyone wanted to forget.

The Struggle of Coming Home

Returning home was the final battle. For many Japanese POWs in WW2, the "peace" was harder than the war.

💡 You might also like: Clayton County News: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gateway to the World

They were often met with silence. Their wives had sometimes remarried, thinking they were dead. Their jobs were gone. There was a prevailing sense of "Why are you back? Why did you survive when so many better men died?"

This collective trauma shaped much of the post-war Japanese psyche. It led to a period of intense work and silence. The veterans didn't talk about the war. The POWs certainly didn't talk about the camps.

Ulrich Straus, a leading expert on this topic, wrote extensively about how these men eventually integrated into the "Salaryman" culture of the 50s and 60s. They channeled that same discipline and "death-defying" loyalty into rebuilding the Japanese economy.

But the scars stayed.

Key Takeaways for History Enthusiasts

If you're researching this topic for a project or just out of personal interest, here are the most important nuances to keep in mind:

- Surrender was a social death. Understand that for a Japanese soldier in 1942, being captured was literally worse than dying. It meant losing your citizenship, your family honor, and your place in the afterlife.

- The Numbers Increased Late-War. While capture was rare in 1942, by the time the Philippines were being retaken and Okinawa was invaded (1945), tens of thousands were being taken prisoner.

- The "Silent" Return. Most Japanese POWs never wrote memoirs. Unlike Allied POWs who formed associations and held reunions, Japanese survivors often stayed in the shadows to protect their families from the "stigma" of their survival.

- Geography Mattered. Your survival rate as a prisoner depended almost entirely on who caught you. The Americans and Australians generally followed the Geneva Convention; the Soviets and the Chinese nationalists/communists often did not.

To truly understand the Pacific War, you have to look at these men. They weren't just "enemies"; they were individuals caught between a brutal military ideology and the basic human instinct to stay alive.

How to Research Further

If you want to go deeper into the primary sources, look for the works of Otis Cary or Ulrich Straus. Their interviews with survivors provide the most authentic look at the "shame" and eventual resilience of these soldiers. You can also visit the Cowra Japanese Garden and Cultural Centre in Australia, which stands today as a memorial to the men who died in the 1944 breakout. It’s a haunting, beautiful place that captures the complexity of this history perfectly.

Stop looking at the Pacific War as a two-dimensional story of "us vs. them." The story of the Japanese prisoner is the story of what happens when a person is forced to survive in a world that told them they had no right to exist.

Check out the digital archives of the Australian War Memorial for actual photos and digitized diaries from the Cowra camp. Seeing the handwritten notes of these men, often writing poetry or drawing sketches of their homes, humanizes a part of history that is too often left in the dark.