Imagine walking through Tokyo in 1989. The ground under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was, on paper, worth more than all the real estate in the entire state of California. That is not a typo. It was a fever dream. People were hailing taxis with 10,000 yen notes because drivers wouldn't stop for anything less. Then, the floor fell out. What followed is often called the Japan lost two decades, a period of stagnation that fundamentally reshaped how the world thinks about money, debt, and aging.

But here is the thing.

If you visit Tokyo today, it doesn't look "lost." The trains run on time to the second. The vending machines are pristine. You won't see the rusted-out hulls of industry that define the American Rust Belt. This creates a massive disconnect for outsiders. We hear "economic collapse" and we think of the Great Depression or 2008. Japan was different. It was a slow, quiet, grinding realization that the future had been canceled.

The Day the Music Stopped

Basically, the whole mess started with the Plaza Accord in 1985. The U.S. dollar was too strong, so world powers agreed to devalue it against the yen. Suddenly, Japanese exports became expensive, and the Bank of Japan panicked. They slashed interest rates to keep the economy moving.

What happens when money is basically free? People gamble.

By 1989, the Nikkei 225 stock index hit nearly 39,000. For context, it took over thirty years for it to claw back to that level. Real estate was even crazier. Banks were lending money based on land values that had no basis in reality. When the Bank of Japan finally realized they were presiding over a giant balloon and started hiking rates in 1990, the balloon didn't just leak. It disintegrated.

Why the Japan lost two decades lasted so long

Most economies crash and then bounce. Japan didn't. Instead, it entered a "Balance Sheet Recession," a term coined by economist Richard Koo. This is a crucial concept. Usually, when interest rates are zero, businesses borrow money to grow. But in Japan, companies were so traumatized by the debt they had taken on during the bubble that they used every spare yen to pay back loans.

They weren't looking to profit. They were looking to survive.

Even when the government begged them to spend, they wouldn't. This led to a "liquidity trap." You can't force people to borrow money if they’re terrified of the future. This fear became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because no one spent, prices dropped. This is deflation. It sounds great—who doesn't want cheaper groceries?—but it’s a trap. If you know a car will be cheaper next year, you wait. If everyone waits, the car company goes bust.

The Zombie Problem

Then there were the "Zombie Banks." Rather than admitting their loans were worthless, Japanese banks kept rolling over the debt of failing companies. They didn't want to realize the losses on their books.

- It kept unproductive companies alive.

- It prevented new, innovative startups from getting capital.

- It tied up the entire country's financial plumbing for years.

Honestly, it was a massive exercise in kicking the can down the road. The government kept building bridges to nowhere—literally—to stimulate the economy. Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio skyrocketed. It’s now the highest in the developed world, sitting well over 250%.

The Demographic Time Bomb

You can't talk about the Japan lost two decades without talking about people. Or the lack of them. Japan is the "canary in the coal mine" for the rest of the world’s aging populations.

In the 1990s, the working-age population began to shrink.

Less workers means less production. More elderly people means more spending on healthcare and less on new gadgets or homes. It is hard to have a booming economy when your customer base is literally disappearing. You've got rural towns where they put dolls in bus stops to make the place feel less empty. That isn't just a sad story; it's a massive economic drag.

Young people saw what happened to their parents—the "Salaryman" dream dying—and they checked out. This gave rise to the hikikomori (social recluses) and the "Freeters" (people who hop between part-time jobs). If the economy doesn't offer a future, why play the game?

Abenomics and the "Third Arrow"

Fast forward to 2012. Shinzo Abe comes to power with a plan: Abenomics. It was a three-pronged attack:

- Massive monetary easing (printing money).

- Fiscal stimulus (government spending).

- Structural reform (making the economy more competitive).

Did it work? Kinda. It stopped the freefall and helped the Nikkei recover. It brought more women into the workforce. But it didn't "fix" the underlying rot of deflationary thinking. People were still hesitant. The culture of "safety first" is hard to break when you’ve lived through twenty years of stagnation.

What we can learn from the "Lost" years

There is a lot of revisionist history about Japan. Some people argue it wasn't a failure at all, but a graceful transition to a post-growth society. Japan remained safe, clean, and cohesive. Compared to the social unrest seen in the U.S. or Europe, Japan looks like a miracle of stability.

But for an economist, it's a warning.

If you let a property bubble get too big, there is no painless way to pop it. If you don't force banks to take their losses early, you end up with zombies. And if you don't address a shrinking population, no amount of money printing will save you.

Actionable Insights for Investors and Policy Makers

Looking at Japan’s history offers some blunt lessons that apply to the global economy today.

👉 See also: Wells Fargo Stock Today: What Most People Get Wrong About the Post-Cap Era

- Watch the Debt-to-GDP, but don't obsess over it: Japan proved a country can carry massive debt if it's held by its own citizens, but it limits your options forever.

- Deflation is harder to kill than inflation: Once people expect prices to fall, it takes decades of radical policy to change their minds.

- Demographics are destiny: If you aren't automating or allowing immigration, a shrinking workforce will eventually cap your growth regardless of how much tech you have.

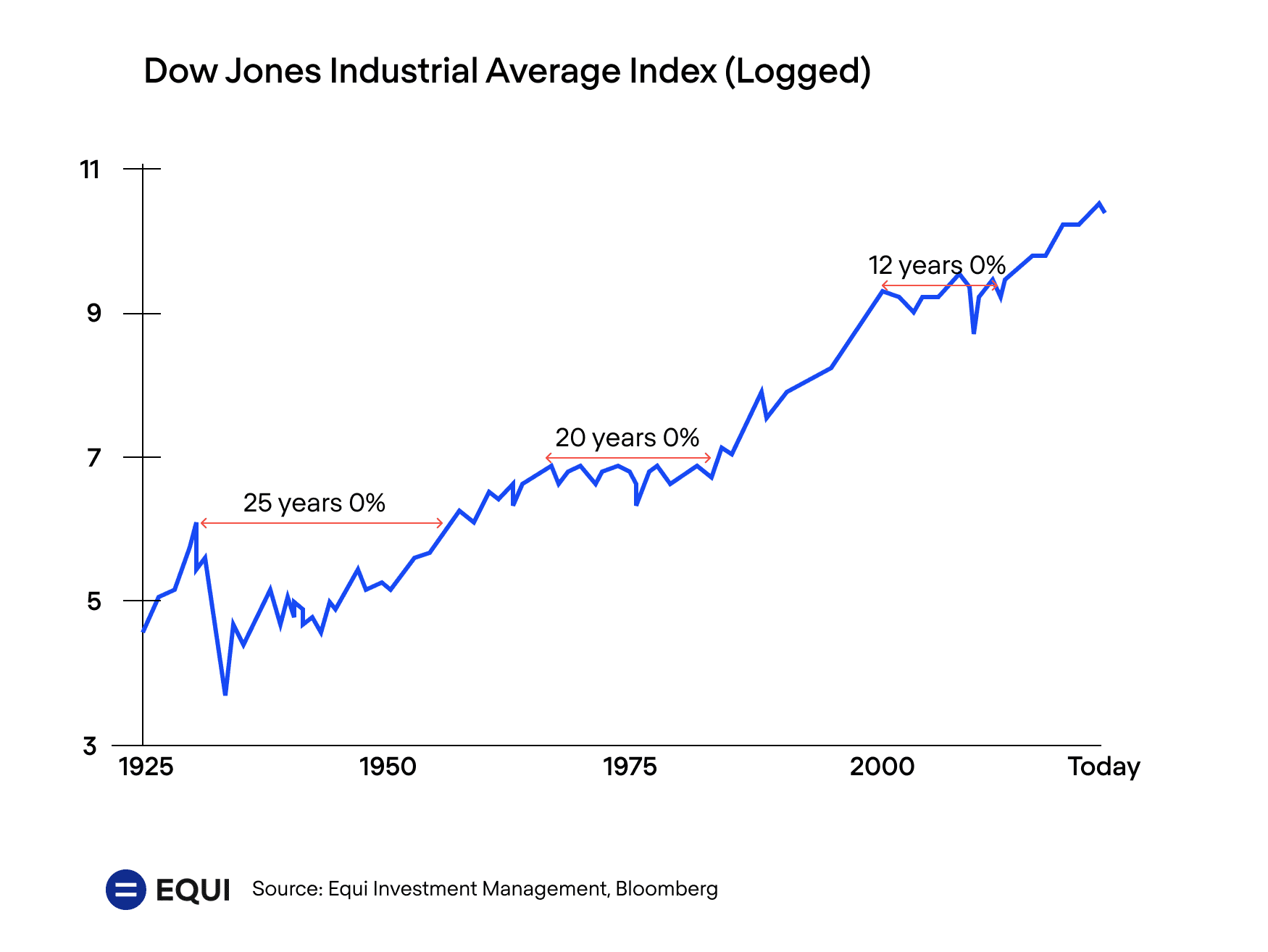

- Diversify your assets: Anyone who bought Tokyo real estate in 1989 is likely still "underwater" today. Never assume a market "can't go down."

Japan’s "lost" years weren't a total loss—they were a transformation. The country moved from being a global manufacturing shark to a quiet, high-tech, aging sanctuary. It’s a different kind of success, but it came at a price that most countries would find unbearable.

To understand where the world is heading, stop looking at Silicon Valley. Look at the bank balance sheets in Tokyo. The "Japanification" of the West is a real risk, and the playbook for avoiding it is written in the scars of the 1990s and 2000s.

Keep a close eye on interest rate trends and labor participation rates in your own country. If you see the "zombie" patterns emerging—where failing companies are kept alive by cheap credit—it’s time to rethink your long-term financial strategy. Don't get caught holding the bag when the music stops.