Honestly, it’s a bit wild when you think about it. Jane Austen only published four novels during her lifetime—Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma—and yet, two centuries later, we treat her like the undisputed queen of the English language. She didn't have a massive social media presence or a multi-book deal with a global publisher. She was just a woman in a drafty parsonage writing on tiny scraps of paper that she’d hide whenever someone walked into the room.

People often think Jane Austen’s novels are just about tea parties and finding a rich husband. That’s a massive misconception. If you actually read the text—really dig into the biting sarcasm and the way she roasts the social hierarchy—you realize she wasn't writing romances. She was writing survival guides for women in a world where they had zero legal or financial power.

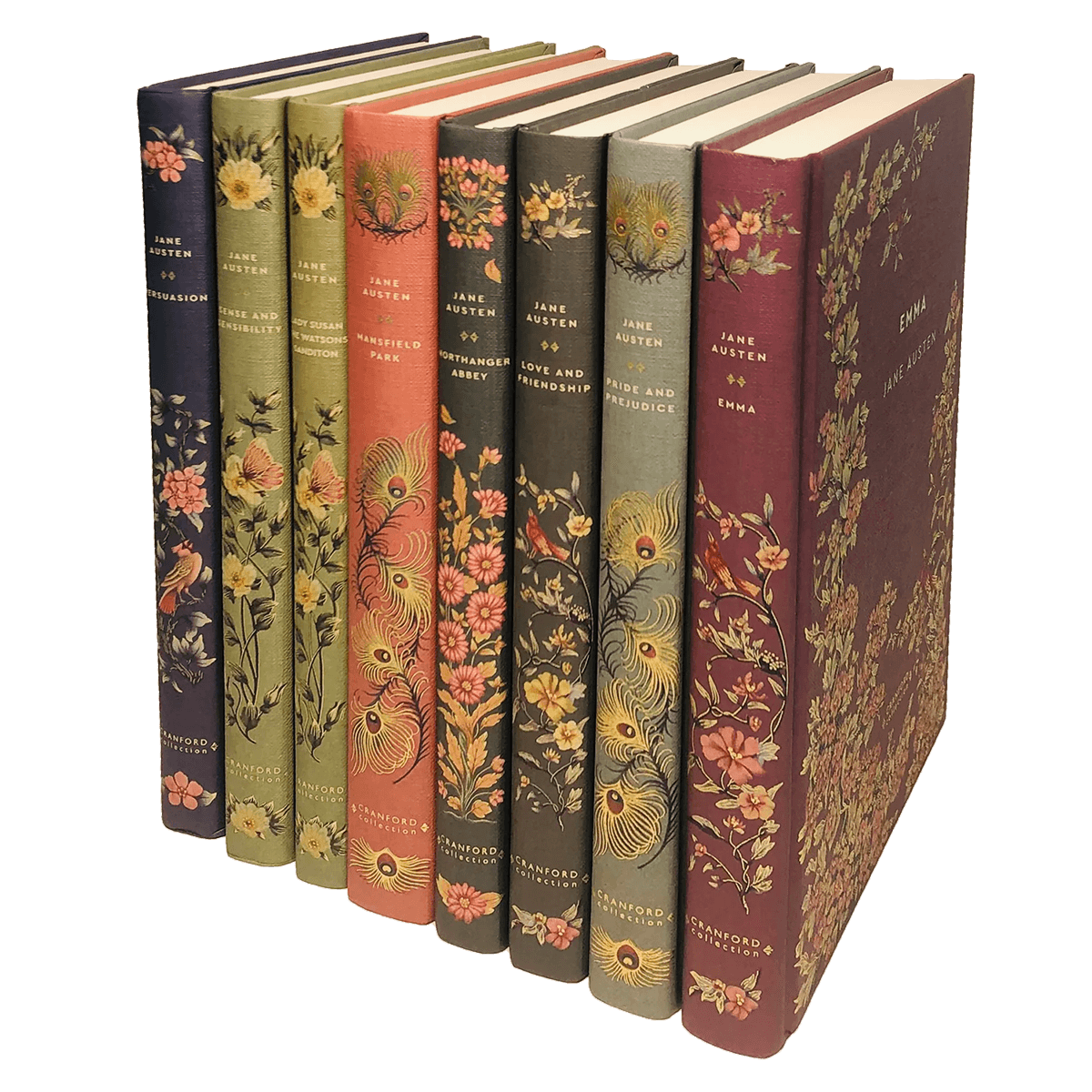

The Big Six: Breaking Down Jane Austen’s Novels

Let's get into the weeds of the actual books. Most people start with Pride and Prejudice, which is fine, but it’s sort of the "gateway drug" to the rest of her bibliography.

Sense and Sensibility (1811)

This was her debut. It follows the Dashwood sisters, Elinor and Marianne, after their father dies and they're basically kicked out of their home by their greedy half-brother. It’s a study in contrast. Elinor is "sense" (composed, logical, keeps her feelings in a box) and Marianne is "sensibility" (emotional, dramatic, screams into pillows).

What people forget is how bleak this book actually is. The financial stakes are terrifying. When Willoughby leaves Marianne, it isn’t just a heartbreak; it’s a social catastrophe. Austen was showing us that being "sensible" isn't just a personality trait—for a woman in 1811, it was a defense mechanism.

Pride and Prejudice (1813)

The GOAT. You know the story: Elizabeth Bennet meets Fitzwilliam Darcy. He’s a jerk; she’s judgmental. They eventually figure it out. But the real genius of Pride and Prejudice is the character of Mr. Bennet. He’s hilarious, right? He spends the whole book making fun of his wife. But if you look closer, he’s actually a pretty terrible father. His sarcasm is a mask for his total failure to provide for his daughters' futures. Austen hides these brutal truths behind some of the wittiest dialogue ever written.

✨ Don't miss: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

Mansfield Park (1814)

This is the one that everyone fights about. Fanny Price is the protagonist, and she’s... well, she’s quiet. She’s physically frail. She doesn't have Elizabeth Bennet’s spark. Some critics, like Kingsley Amis, famously hated Fanny, calling her "insufferable." But modern scholars like Edward Said have pointed out the darker undercurrents here, specifically the references to the Antiguan slave trade which funded the luxurious lifestyle of the Bertram family. It’s Austen’s most complex and uncomfortable work.

Emma (1815)

Austen famously said she was going to create a heroine "whom no one but myself will much like." Emma Woodhouse is rich, spoiled, and thinks she’s a master matchmaker. She’s wrong about almost everything. The brilliance of Emma is the "free indirect style"—a narrative technique where the narrator’s voice blends with Emma’s thoughts. You think you’re seeing the world objectively, but you’re actually seeing it through Emma’s delusions. It’s a technical masterpiece that basically paved the way for the modern psychological novel.

Northanger Abbey (1817)

Technically written much earlier, but published posthumously. It’s a parody of Gothic novels. Catherine Morland is a teenager who reads too many scary books and starts imagining that her friend’s dad is a murderer. It’s Meta. It’s Austen’s version of a "Scream" movie where the characters are aware of the tropes they’re living in.

Persuasion (1817)

Her final completed novel and, honestly, her best. Anne Elliot is 27—an "old maid" by Regency standards. Eight years prior, she was talked out of marrying the love of her life, Captain Wentworth, because he wasn’t rich enough. Now, he’s back, he’s loaded, and he’s still mad at her. It’s a story about "second chances" and the regret that comes with maturity. It feels much more "autumnal" and melancholic than her earlier stuff.

Why the "Marriage Plot" Isn't What You Think

If you think Jane Austen’s novels are just about weddings, you’re missing the point. Marriage was the only career path available to women of her class. There was no "starting a small business" or "climbing the corporate ladder." If you didn't marry, you were a governess (basically a servant with better grammar) or you lived off the charity of relatives who probably resented you.

🔗 Read more: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

When Charlotte Lucas marries the dunderheaded Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth is horrified. But Charlotte is being pragmatic. She’s 27, she has no money, and she doesn't want to be a burden on her brothers. Austen isn't celebrating the romance there; she’s critiquing the economy that forces a smart woman to marry a fool just to have a roof over her head.

The Fragmented Works and Juvenilia

Most people stop at the six novels, but if you want the full picture, you have to look at the unfinished stuff.

- Sanditon: She was writing this while she was literally dying. It’s set in a seaside resort and feels incredibly modern. It’s obsessed with health, hypochondria, and the rise of consumerism.

- The Watsons: Another unfinished fragment that is incredibly grim about poverty.

- Lady Susan: A short epistolary novel (written in letters) about a woman who is basically a sociopath. It’s hilarious and totally different from the "polite" tone of her later books.

The Legacy: From Bridget Jones to Bridgerton

We’re still obsessed. We’ve had the 1995 Colin Firth "wet shirt" moment, the 2005 Keira Knightley "moody fields" version, and countless modern retellings like Clueless (which is just Emma in Beverly Hills).

But why?

It’s because human nature hasn't changed. We still deal with "Karens" (Lady Catherine de Bourgh), "fuckboys" (George Wickham), and the crushing anxiety of trying to fit into a social circle that doesn't really want us there. Austen’s sharp eye for hypocrisy is universal. She didn't need to write about wars or kings to be important; she found the entire universe in a "country village" and three or four families.

💡 You might also like: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

How to Actually Read Jane Austen Today

If you’re diving into these books for the first time, or trying to re-read them without the "high school English class" trauma, here are some tips.

First, read the footnotes. Seriously. Half of Austen’s jokes rely on you knowing that a "barouche-landau" is the Regency equivalent of a Ferrari, or that having "ten thousand a year" makes you a multi-millionaire in today’s money. Without the context of the money, the stakes feel low. With it, they feel like a thriller.

Second, listen for the sarcasm. Austen is mean. In a good way. She hates stupid people, and she’s not afraid to let you know. When she describes a character as having "a very good opinion of himself," she’s calling him an arrogant idiot.

Third, don't rush. These aren't thrillers. They’re character studies. The "action" happens in the drawing-room conversations and the subtext of a dance.

Actionable Next Steps for the Aspiring Janeite:

- Start with Pride and Prejudice or Northanger Abbey. They are the most accessible. Avoid Mansfield Park until you’ve got a few others under your belt; it’s a "level 10" Austen book.

- Check out the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA). They have incredible resources and deep-dive essays on everything from the fashion of the era to the legalities of "entailment."

- Watch a faithful adaptation first. If the language feels dense, watch the 1995 Pride and Prejudice miniseries. It follows the book almost line-for-line and helps you visualize who is who before you tackle the text.

- Look into the "Juvenilia." If you think she’s too "proper," read Love and Freindship (yes, she misspelled it). She wrote it as a kid, and it’s basically a parody of people fainting and being overly dramatic. It’s proof that she was a rebel from the start.

Jane Austen didn't write about the Napoleonic Wars that were raging while she held her pen. She wrote about the war happening in the heart and the bank account. That’s why we’re still talking about her.