The first time I saw the "Cosmic Cliffs" in the Carina Nebula, I didn't actually think it was real. It looked like a prog-rock album cover from the seventies. But those james webb telescope photos are very real, and they’ve basically broken our collective brain regarding what space actually looks like. We spent decades getting used to the blurry, albeit beautiful, smudges from Hubble. Now? Everything is crisp. It’s almost unsettling.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) isn't just a bigger camera. It’s a heat-seeker. Because it sits out at Lagrange point 2—about 1.5 million kilometers away from our warm, noisy planet—it can see infrared light that has been traveling through the vacuum of space for over 13 billion years. If you’ve ever wondered why these images look so radically different from what we saw in the 90s, it’s because Webb is looking through the dust, not just at it.

The Pillars of Creation and the infrared trick

Take the Pillars of Creation. You’ve seen the 1995 version. It was iconic. It looked like giant, ghostly fingers of gas reaching out into the void. But when you look at the james webb telescope photos of that same region, the "ghosts" disappear. Instead of opaque walls of cold gas, we see through them. We see the thousands of sparkling red stars that were previously hidden inside those clouds.

It’s a bit like taking a photo of a foggy forest with a regular camera versus a thermal one. The regular camera shows you the fog; the thermal camera shows you the deer standing behind the trees.

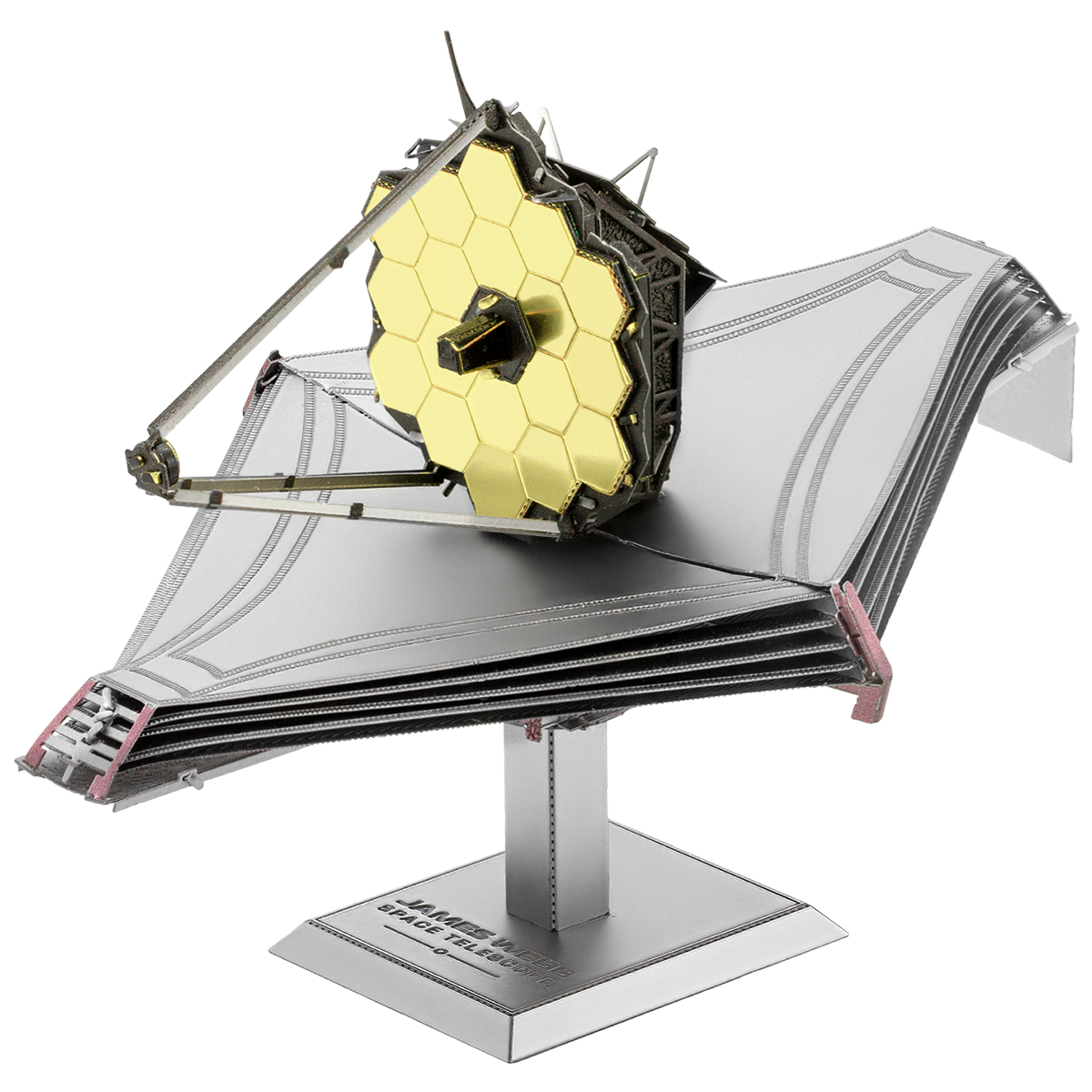

NASA’s Jane Rigby, a project scientist for the mission, has often pointed out that the telescope is actually over-performing. The optics are cleaner than they predicted. This means the "point spread function"—basically how the telescope handles a single point of light—is so sharp that we’re seeing details in distant galaxies that we thought would be impossible to resolve. Honestly, it’s kind of a miracle the mirrors unfolded at all, considering there were over 300 "single point failures" during the deployment. If one thing snagged, the $10 billion project was a floating piece of junk.

Why the colors aren't "fake" but are definitely "made"

A common gripe you’ll see on Reddit or Twitter is that these photos are "fake" because they’re colorized. Well, yeah. They are. But not in the way a coloring book is.

Human eyes can’t see infrared. If you stood right next to the Southern Ring Nebula, you wouldn't see those vibrant oranges and blues; you'd see... well, not much. The scientists use a process called "chromatic ordering." They take the longest wavelengths of infrared and assign them to red. The shortest ones get assigned to blue. It’s a direct translation of data into a visual language we can understand. It’s more like a translation of a book from a language you don't speak into one you do. The story stays the same; only the medium changes.

Deep Fields and the "clumping" of time

One of the most mind-bending james webb telescope photos is the SMACS 0723 Deep Field. It was the first "full-color" image released. If you held a grain of sand at arm's length, that is the tiny sliver of sky you’re looking at in that photo.

Look closely at the center of that image. You’ll see these weird, stretched-out arcs of light. That’s not a camera glitch. It’s gravitational lensing. There is so much mass in the foreground galaxies that they are literally warping the fabric of spacetime, acting like a cosmic magnifying glass. It’s bending the light from galaxies behind them.

✨ Don't miss: Apple Pencil Pro: What Most People Get Wrong

We are seeing light that started its journey when the universe was in its infancy. Some of these galaxies are over 13.1 billion years old. Since the universe is about 13.8 billion years old, we are basically looking at the "toddler" phase of existence. It turns out, early galaxies were much more organized and numerous than our previous models suggested. This is actually causing a bit of a "crisis" in cosmology. Some researchers, like Allison Kirkpatrick at the University of Kansas, have noted that the data from Webb is challenging the "standard model" of how quickly the universe grew up.

The things nobody mentions about the "sparkles"

Have you noticed those bright stars in the photos always have eight distinct "spikes" coming off them? Those are called diffraction spikes. They aren't part of the star. They are a "signature" of the telescope's design. Because the JWST has a hexagonal mirror and a three-legged strut holding the secondary mirror, the light diffracted around those edges creates that specific eight-point pattern.

Hubble’s stars usually have four spikes.

It’s a tiny detail, but it’s how you can instantly tell which telescope took the photo. If it looks like a compass rose, it’s Webb. These spikes are technically artifacts—distortions—but they’ve become a hallmark of this new era of astronomy.

Searching for water on other worlds

The james webb telescope photos aren't just about pretty nebulae. Some of the most important "photos" are actually graphs called spectra. When Webb looks at an exoplanet—a planet orbiting another star—it waits for that planet to pass in front of the star. The starlight filters through the planet's atmosphere.

By analyzing which colors of light are absorbed, we can tell what the air on that planet is made of. We’ve already found clear signals of water, sulfur dioxide, and even carbon dioxide on planets like WASP-39 b. We are no longer just guessing if other worlds have atmospheres. We are reading their chemical signatures like a grocery receipt.

💡 You might also like: How Create Hexagon Fans Blender: Why Your Topology Probably Sucks and How to Fix It

The Steals of the Show: Jupiter and Saturn

While most of the hype focuses on deep space, Webb’s photos of our own solar system are low-key the most impressive. Have you seen the shot of Jupiter? It shows the aurorae at the poles glowing in infrared. You can see the rings—yes, Jupiter has rings—which are usually invisible.

Then there’s Saturn. In the JWST shots, the planet itself looks almost black because methane gas in its atmosphere absorbs most of the sunlight. But the rings? They stay brilliantly bright. It looks like a glowing crown floating in a dark room. It’s a perspective we simply couldn’t get from Earth-based telescopes or even the aging Hubble.

Moving beyond the "pretty picture" phase

If you want to actually engage with these images rather than just scrolling past them, there are a few things you should do. First, stop looking at them on a phone screen. The raw files released by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) are massive. On a small screen, you lose the "clutter" of the background.

In almost every Webb photo, even the "empty" space between stars is packed with distant galaxies. Thousands of them. Each one contains billions of stars. It’s a scale that is impossible to grasp until you zoom in on a high-resolution monitor and realize that the "speck" in the corner is actually a spiral galaxy twice the size of the Milky Way.

👉 See also: Why the Polaroid 16MP Waterproof Digital Camera is Still a Weirdly Good Idea

Actionable ways to explore the cosmos

Don't just take my word for it. You can actually access the same data the pros use.

- Visit the MAST Archive: The Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes is where the raw data lives. It’s public. If you’re tech-savvy, you can download the FITS files and process them yourself.

- Use the WebbCompare tool: There are several community-made websites that let you slide a bar back and forth between a Hubble photo and a Webb photo of the same region. It’s the best way to see exactly what $10 billion buys you in terms of clarity.

- Look for the "unseen": When looking at a new release, ignore the big colorful object in the middle for a second. Look at the tiny red dots in the background. Those are usually the most scientifically significant objects in the frame—the oldest galaxies ever seen.

- Follow the "First Light" blog: NASA keeps a running log of the technical challenges and "micro-meteoroid" hits the telescope takes. It’s a reminder that this machine is currently being pelted by tiny space rocks while it sends us these masterpieces.

The reality of the james webb telescope photos is that they are a time machine. We are seeing the universe as it was, not as it is. Because light takes time to travel, the further we look, the further back in time we see. Webb is currently peering into the "Dark Ages" of the universe, looking for the very first stars to ever turn on. Every new photo is a page of a history book that we’re finally learning how to read.