You’ve probably seen the headlines. They scream about "shattering the laws of physics" or "finding the impossible." Whenever James Webb telescope images black hole data hits the public, the internet sort of melts down. But honestly? Most of what you’re seeing in those viral thumbnails isn't exactly what the telescope "sees."

Black holes are, by definition, dark. They don't emit light. So, when we talk about Webb capturing them, we're really talking about the chaos happening right on their doorstep. Webb isn't looking for a dark circle; it’s looking for the glowing, screaming gas and dust being ripped apart by gravity so intense it bends time.

The Real Deal with Webb's Infrared Vision

Most people are used to the "donut" photo from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). That was a radio wave composite. Webb is different. It operates in the infrared spectrum. This is a massive deal because black holes are usually tucked away behind thick, suffocating clouds of cosmic dust. Visible light hits that dust and just stops. Infrared light, however, slips through like a ghost.

When the James Webb telescope images black hole environments, it’s actually peering through the "curtains" of the galaxy. It’s looking at the mid-infrared and near-infrared signatures of the material orbiting the Event Horizon. In 2023 and 2024, Webb targeted the supermassive black hole at the center of our own galaxy, Sagittarius A*, and several others in the "Cosmic Noon" era of the universe. It found things that, frankly, shouldn't be there.

We’re talking about black holes that are way too big for their age.

Why the "Little Red Dots" Changed Everything

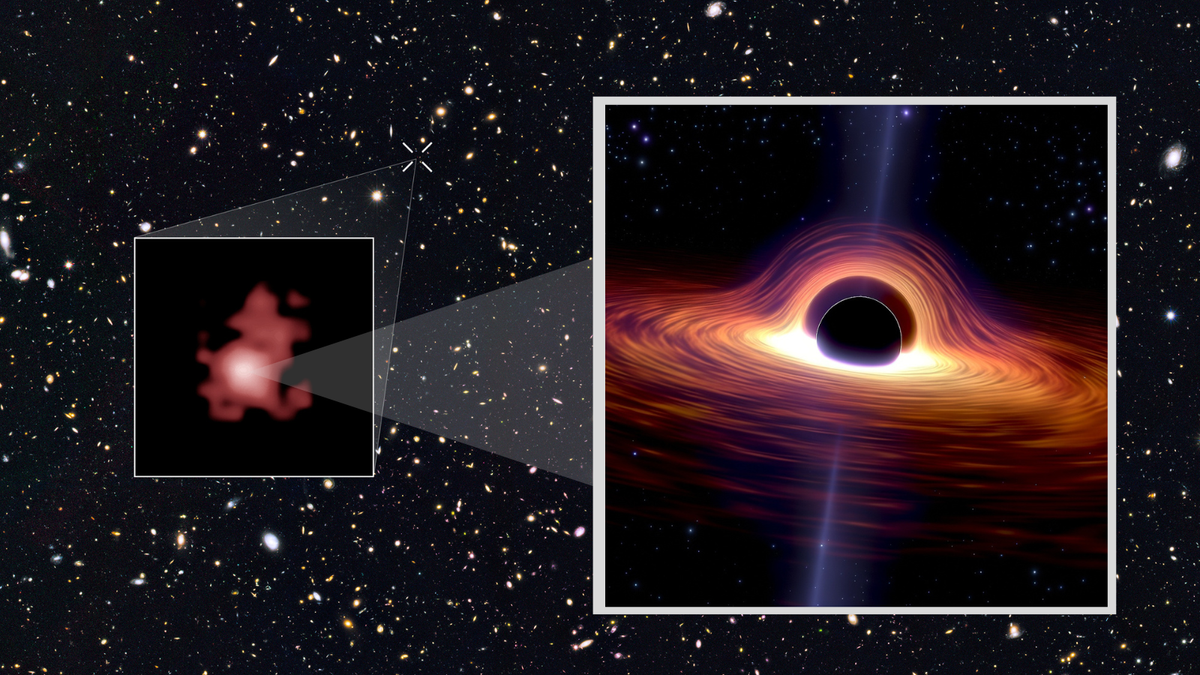

Scientists, including researchers like Jorryt Matthee from ETH Zürich, started noticing these tiny, unassuming red dots in Webb's deep-field images. At first glance, they look like nothing. Just specs. But when the data was crunched, it turned out these "Little Red Dots" were actually "baby" quasars—supermassive black holes in the very early universe.

🔗 Read more: Samsung TV Bluetooth Speaker Setup: Why Your Audio Sync Is Probably Lagging

The problem? They are huge.

If you follow the standard model of how galaxies grow, these black holes are basically teenagers who are already seven feet tall. They shouldn't have had enough time to eat that much matter. This is why you see so many articles saying Webb "broke" physics. It didn’t break physics, but it definitely tossed our old textbooks into the shredder. We used to think galaxies formed first, and then black holes grew inside them. Now, Webb’s data suggests black holes might be the "seeds" that pull galaxies together in the first place.

Looking at the Monster in NGC 1433

One of the most stunning examples of James Webb telescope images black hole influence isn't a picture of the hole itself, but its "exhaust." Look at the galaxy NGC 1433. Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) captured the galactic center in a way that shows exactly how the central black hole is "choking" the galaxy.

You can see these double rings of star formation. The black hole at the center is releasing energy that actually blows away the gas needed to make new stars. It’s a weird paradox. The black hole is a creator because its gravity holds the galaxy together, but it's also a destroyer that starves the galaxy of its ability to grow.

The CEERS 1019 Breakthrough

If you want to get technical, the record-breaker for a while was CEERS 1019. This is a black hole that existed just 570 million years after the Big Bang. For context, the universe is about 13.8 billion years old. Seeing something that clearly from that long ago is basically a miracle of engineering.

Webb didn't just take a "picture" of it. It used spectroscopy. This is where the telescope breaks down light into a rainbow to see the chemical fingerprints of what it’s looking at. The data showed that this black hole was roughly 9 million times the mass of our sun. That sounds big, but in the world of supermassive black holes, it’s actually a "lightweight." Finding a "small" supermassive black hole so early in time is actually more confusing to scientists than finding a big one, because it suggests there are way more of these things out there than we ever imagined.

Is it a "Photo" or a Map?

Let's be real: Webb's raw data looks like garbage to the human eye. It's all digital noise and black-and-white pixels. When we see those gorgeous gold and purple images, we’re looking at a translation.

- Near-Infrared (NIRCam): Usually mapped to blue and cyan colors. This shows stars and hot gas.

- Mid-Infrared (MIRI): Usually mapped to reds and oranges. This shows the "cool" dust—the soot of the universe.

When the James Webb telescope images black hole regions, the colors tell a story. If a region is bright red, it means there’s a lot of dust being heated up by the black hole’s radiation. If it’s bright blue, you’re seeing the violent, high-energy environment right near the accretion disk.

The Misconception of "Sucking Things In"

A big mistake people make when looking at these images is thinking of the black hole as a cosmic vacuum cleaner. It’s not. If our Sun were replaced by a black hole of the same mass, Earth wouldn't get "sucked in." We’d just keep orbiting it in the dark (and freeze, obviously).

Webb shows us this stability. In many images, we see stars orbiting the central black hole in perfect, beautiful ellipses. The only things that get "eaten" are the unlucky gas clouds that get too close and lose their orbital velocity. Webb’s high resolution allows us to see these individual gas filaments being stretched like spaghetti—a process scientists literally call "spaghettification."

💡 You might also like: International Space Station Assembly: How We Actually Built the Giant in the Sky

What’s Next for Webb and the Dark Hearts of Galaxies?

The mission isn't even close to done. We are currently waiting for more data on "overmassive" black holes in the early universe. There’s a theory floating around the hallowed halls of NASA and the ESA (European Space Agency) that black holes might have formed from the direct collapse of massive gas clouds, skipping the "star" phase entirely.

If Webb confirms this, it changes everything we know about the timeline of the universe.

We’re also looking forward to more "multi-messenger" astronomy. This is where Webb looks at a black hole at the same time as the Chandra X-ray Observatory or the Event Horizon Telescope. By combining Webb’s infrared (the dust) with Chandra’s X-rays (the heat), we get a 3D understanding of these monsters.

How to Follow the Discoveries Yourself

If you’re obsessed with this stuff, don't just wait for the news to filter through social media. You can actually see the "fresh" data almost as fast as the scientists do.

- Check the MAST Archive: The Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes is where the raw data lives. It’s public.

- Follow the "Webb Observations" Twitter/X bots: There are accounts that post every time the telescope moves to a new target.

- Look for the "Spectrum": When a new image drops, look for the graph next to it. That graph (the spectroscopy) usually holds 90% of the actual scientific discovery.

The James Webb telescope images black hole research is fundamentally changing our place in the cosmos. We used to think we lived in a universe of stars. Now, it’s looking more and more like we live in a universe of black holes, and the stars are just the decorations they've collected along the way.

To truly understand these findings, stop looking for the "bright light" and start looking at how the black hole shapes the space around it. The real story isn't the hole; it's the ripple effect it has on every star and galaxy for millions of light-years. Keep an eye on the monthly releases from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI)—the next "impossible" discovery is usually only a few weeks away.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

To get the most out of these discoveries, you should visit the official Webb Space Telescope gallery at webbtelescope.org and use their "Compare" tool. This allows you to slide between Hubble’s visible light views and Webb’s infrared views of the same black hole regions. Seeing the dust "disappear" in real-time is the best way to grasp why this technology is such a massive leap forward for human knowledge.