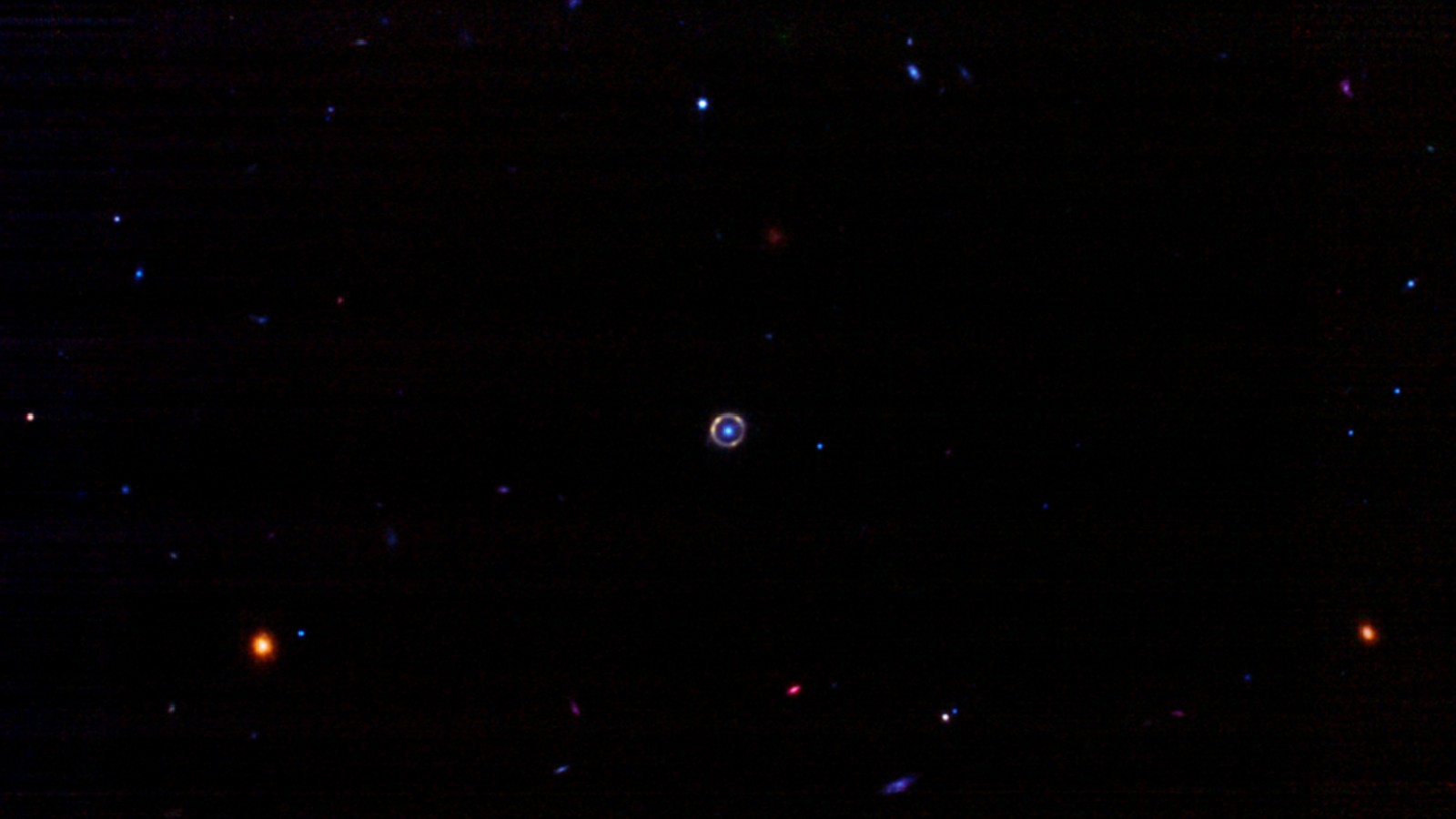

Space is weird. Just when we think we’ve mapped out the basic rules of how light travels across the universe, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) goes and finds something that looks like it belongs in a hall of mirrors. We are talking about the first-ever "Einstein zig-zag."

Einstein’s General Relativity tells us that massive objects—like entire clusters of galaxies—actually warp the fabric of space-time. If a light beam from a distant source passes near one of these heavy hitters, it bends. Usually, we see this as an "Einstein Ring" or a simple arc. But what happens when you have two massive objects perfectly misaligned in just the right way? You get a zig-zag. The light doesn't just bend once; it gets yanked back and forth across the cosmic stage.

What is a Zig-Zag anyway?

Most people are familiar with gravitational lensing. It's basically a natural magnifying glass in space. But this new discovery, involving the quasar J1721+8842, is a whole different beast. Astronomers originally thought they were looking at a standard quadruply-imaged quasar. You know, one light source appearing as four dots because a big galaxy is sitting in front of it.

But the JWST data showed something "impossible."

There weren't just four images. There were six. And the way they were positioned suggested the light was bouncing between two different gravitational "deflectors" at different distances from Earth. Imagine a skier going down a slalom course. The light isn't just curving; it’s being redirected by one galaxy cluster, then swinging back the other way because of a second one. This "zig-zag" geometry is a unicorn in the world of astrophysics.

The Math Behind the Madness

To understand why this is a big deal, we have to look at the Hubble Constant ($H_0$). This is the number that tells us how fast the universe is expanding. The problem is, different ways of measuring it give different results. This is called the "Hubble Tension," and it’s currently the biggest headache in cosmology.

The Einstein zig-zag is like a gift from the heavens for solving this. Because the light takes different paths—the zig and the zag—each "version" of the quasar we see arrives at a slightly different time. One path might be a few days or weeks longer than the other. By measuring these time delays with the precision of the JWST, researchers can calculate the expansion of the universe with a level of accuracy that was basically science fiction ten years ago.

Martin Millon and his team at EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) have been leading the charge on this. They realized that this specific configuration—a double-plane lens—is significantly more sensitive to the underlying geometry of the universe than a single lens. It’s like having two checkpoints in a race instead of one; you get much better data on the runner’s speed.

🔗 Read more: Système International SI Units: Why Your Measurements Are More High-Tech Than You Think

Why JWST is the Only Tool for the Job

Honestly, Hubble couldn't have done this. Don't get me wrong, Hubble is a legend. But it lacks the infrared "eyes" and the sheer resolution to separate these tiny, faint dots of light from the glare of the foreground galaxies.

The JWST uses its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) to pierce through cosmic dust and see the distinct signatures of each lensed image. It's not just about taking a pretty picture. It's about spectroscopy. The telescope breaks the light down into its component colors to prove that all six images are, in fact, the same quasar.

The "Zig-Zag" Breakdown:

- The Source: A supermassive black hole (quasar) billions of light-years away.

- The First Deflector: A massive galaxy that bends the light initially.

- The Second Deflector: Another galaxy, further along the path, that bends it back.

- The Result: A complex pattern of six images that trace the "zig-zag" path of the photons.

It sounds complex because it is. We are watching light perform acrobatics over billions of years just to reach our sensors.

What Most People Get Wrong

A common misconception is that the light is actually "bouncing" off something. It’s not. There are no mirrors in space (well, except for the ones we put there). The light is following a straight line through curved space. If you were riding on a photon, you’d feel like you were going perfectly straight. It’s the "road" itself that is twisted.

Another thing: people think these discoveries are just for academic papers. But this "zig-zag" might be the key to understanding Dark Energy. If the expansion of the universe is changing in ways we don't expect, these multi-plane lenses will be the first things to show it. We’re basically using the universe’s own quirks to fact-check our laws of physics.

The Reality of Dark Matter

We also have to talk about the "invisible" stuff. The galaxies doing the lensing aren't just made of stars. In fact, most of their mass is Dark Matter. By studying the zig-zag, astronomers can map out exactly where the Dark Matter is located in those foreground galaxies. It’s like seeing the shadow of a ghost.

🔗 Read more: macOS Tahoe Public Beta: Why You Should Probably Just Wait

If the light doesn't bend exactly where the "visible" stars are, we know there’s an invisible clump of mass pulling on it. The precision of the JWST allows us to see these tiny "sub-halos" of Dark Matter. This isn't just about one weird quasar; it's about weighing the invisible parts of our universe.

The Future of Lensing Research

We are just scratching the surface. J1721+8842 is the first confirmed case, but now that we know what to look for, the hunt is on. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is coming online soon, is expected to find thousands of new lensed systems.

When you combine the wide-field survey of Rubin with the "zoom-in" power of the JWST, we’re going to find even weirder stuff. Triple-plane lenses? Maybe even more complex "loop-de-loops" of light? It sounds crazy, but twenty years ago, a zig-zag sounded crazy too.

What This Means for You

You might be wondering why this matters to anyone who isn't an astrophysicist. Fair question.

First, it validates the tech. The JWST was a massive gamble—$10 billion and decades of work. Seeing it pull off "impossible" observations like this proves that we can build machines that work perfectly millions of miles away.

Second, it’s about our origin story. Understanding the Hubble Constant and Dark Energy tells us how the universe began and how it will end. Does it expand forever? Does it collapse? The zig-zag is a tiny piece of that massive puzzle.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you want to stay on top of these discoveries without getting lost in the jargon, here is how to track the progress:

Follow the "Surveys" Don't just look for "JWST" news. Search for "COSMOS-Web" or "UNCOVER" survey results. These are the large-scale programs that find these rare objects before they get individual press releases.

💡 You might also like: How to fix an Android charger when your phone refuses to cooperate

Use Public Data Tools The Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) is where the raw data lives. You don't have to be a pro to look at the image galleries. You can see the "zig-zag" data yourself if you know the object ID (J1721+8842).

Monitor the Hubble Tension Debate Keep an eye on the "Distance Ladder" vs. "CMB" measurements. The zig-zag discovery is a huge win for the Distance Ladder side (the people who measure things directly), and it might finally force a rewrite of some textbook physics.

The "Einstein zig-zag" isn't just a visual fluke. It’s a precision instrument provided by the universe itself. By confirming its existence, the James Webb Telescope hasn't just shown us a new image; it’s given us a new yardstick for reality. We’re finally seeing the universe for what it is: a complex, warped, and endlessly surprising place where even light doesn't always take the path you'd expect.