Space is actually pretty dusty. It’s a messy, chaotic graveyard of gas and ancient debris. When we look at the latest James Webb shots of nebula formations, we aren't just seeing pretty pictures; we are seeing through a cosmic fog that has blocked our view for centuries. Honestly, if you looked at the Carina Nebula with your own eyes from a spaceship window, it wouldn't look like those vibrant, glowing posters on your wall.

Human eyes are limited. We see visible light. But the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) sees in infrared. This matters because infrared light literally slides through thick clouds of interstellar dust like it isn't even there.

Why the Pillars of Creation Look "Ghostly" Now

Take the Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula. Back in 1995, Hubble made these famous. They looked like solid, towering mountains of stone in space. They were majestic, sure, but they were also opaque. You couldn't see what was happening inside them.

When the James Webb shots of nebula data for the Pillars started coming in, the "mountains" suddenly became semi-transparent. It’s kinda like looking at a dense forest in the winter after all the leaves have fallen. Suddenly, you see the nests. In this case, the "nests" are protostars—tiny, angry red dots of collapsing gas that are finally becoming stars.

NASA’s Klaus Pontoppidan, a project scientist for Webb, has pointed out that these images aren't just "colorized" for fun. The colors represent specific wavelengths of infrared light. For instance, that eerie, translucent blue gas you see in the Webb version of the Pillars? That’s actually a result of the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) capturing the "soot-like" dust that’s usually invisible. It’s wild to think that what looks like a void to Hubble is a crowded construction site to Webb.

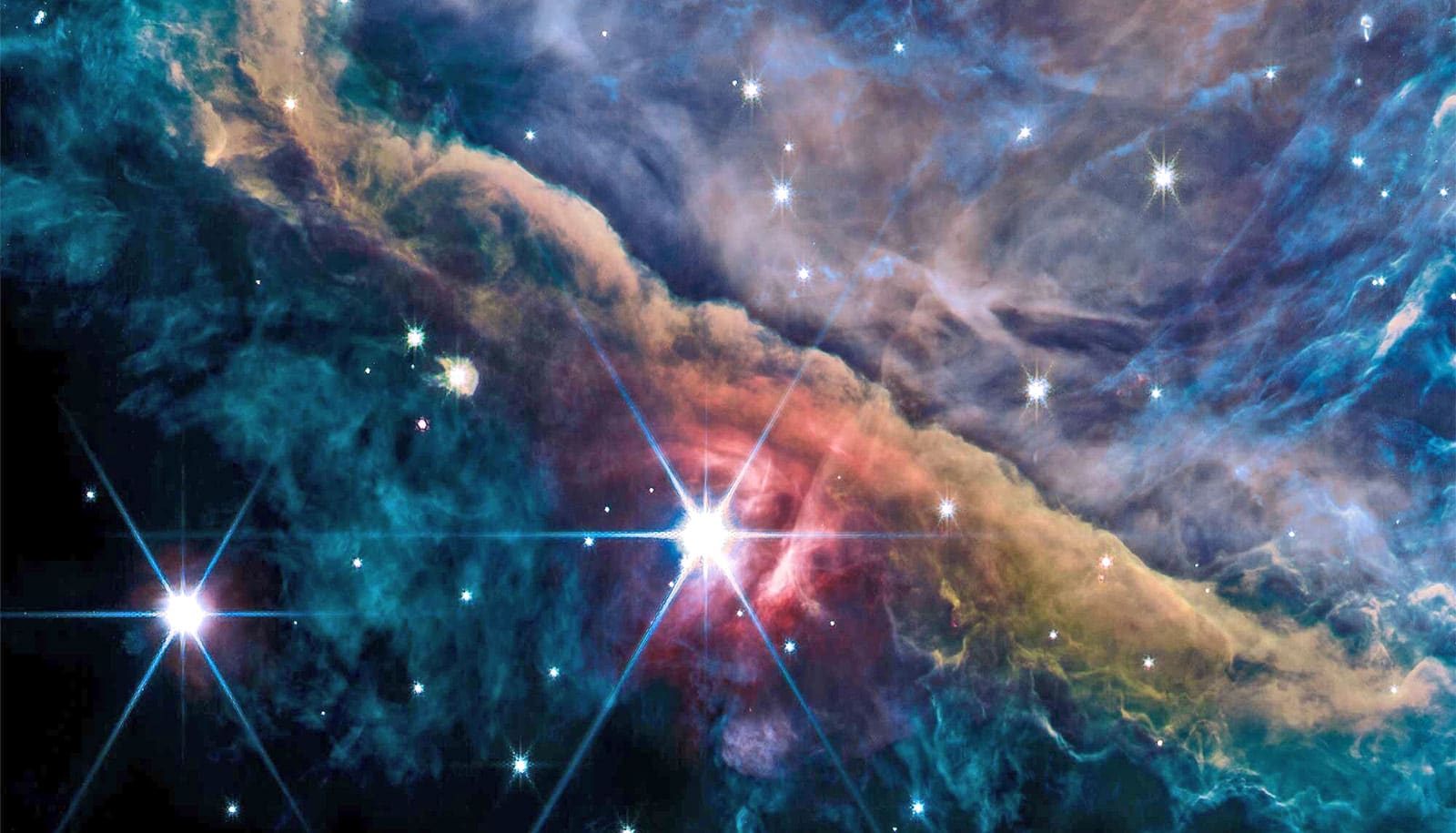

The Carina Nebula and the "Cosmic Cliffs"

You’ve probably seen the "Cosmic Cliffs." It’s arguably the most famous of the James Webb shots of nebula released so far. It looks like a jagged mountain range under a starry night sky.

Basically, what you're looking at is the edge of a giant, gaseous cavity. It was carved out by intense ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from massive, hot, young stars located just above the frame. Those "peaks" are actually about seven light-years high. Think about that. Seven light-years. The distance from our sun to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is only about four light-years.

One of the coolest things Webb found here that nobody really expected was "stellar nurseries" in their earliest stages. Because Webb can see the heat signature of these objects, it found dozens of individual stars that were completely hidden from every other telescope in history. It’s not just a photo; it’s a map of how we were born.

The Southern Ring Nebula: A Tale of Two Stars

The Southern Ring Nebula (NGC 3132) is another example where Webb just completely changed the narrative. For a long time, we thought there was a star at the center. We knew it was a "planetary nebula"—which has nothing to do with planets, by the way, it’s just a dying star shedding its skin.

But the James Webb shots of nebula NGC 3132 revealed something spicy. There isn't just one star. There are two. Or maybe even more.

The dying star is actually shrouded in dust. It’s been "stirring the pot" of gas around it, creating those intricate, wavy patterns. It’s almost like watching a sprinkler system rotate in slow motion over thousands of years. The NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) showed the stars clearly, while the MIRI instrument showed the dust that the dying star had puffed out. Scientists like Amber Straughn have noted that this helps us understand the "end-of-life" cycle for stars similar to our own sun.

📖 Related: Protpedia and the Shift Toward Natural Language in Protein Design

Is It All Just Photoshop?

People ask this a lot. "Is it fake?"

Sorta, but not really. Webb doesn't take "color" photos because infrared light has no color that humans can perceive. If you stood next to the telescope, you’d see nothing. Total darkness.

The scientists use a process called "chromatic ordering." They take the shortest wavelengths of infrared and turn them blue. The medium ones become green. The longest ones become red. It’s a literal translation of data into a visual language. It’s like translating a book from a language you don't speak into one you do. The story is the same; you just changed the medium so you could actually understand it.

The data is real. The structures are real. The temperatures are real. We just need the "Photoshop" to make it make sense to our monkey brains.

Dealing With the Scale of These Things

It’s hard to wrap your head around the size. When you look at the Tarantula Nebula—a massive star-forming region in the Large Magellanic Cloud—you’re looking at something 161,000 light-years away.

Webb’s view of the Tarantula Nebula is significant because it showed us "hairy" filaments of gas that look like spider silk. But inside those filaments are thousands of young stars that were previously obscured. This region is a favorite for astronomers because the chemical composition is similar to the "Cosmic Noon"—a period billions of years ago when star formation was at its peak in the universe. By looking at this nebula, we are essentially looking at a local laboratory of the early universe.

Moving Beyond the Pretty Pictures

If you want to really appreciate these James Webb shots of nebula, you have to look past the desktop wallpaper vibes.

- Look for the diffraction spikes. Those "six-pointed stars" you see? Those aren't real objects. That’s an artifact of the telescope’s hexagonal mirrors. If you see a star with those spikes, it’s a foreground star in our own galaxy. If it’s a tiny smudge without spikes, it’s likely a galaxy millions of light-years behind the nebula.

- Check the contrast. Notice how some areas are dark and "empty" while others are glowing. The dark areas aren't empty; they are usually "Bok globules"—clouds of dust so dense that even infrared struggles to get through. That’s where the most massive stars are currently being "cooked."

- Compare instruments. Often, NASA releases two versions of the same nebula. One is from NIRCam (looks sparkly and detailed) and one is from MIRI (looks moody, orange, and dusty). The NIRCam version shows the stars. The MIRI version shows the "bones" of the nebula—the heavy elements like carbon and silicates.

The next time a new batch of images drops, don't just scroll past. Zoom in. Look for the tiny, faint red dots. Each one of those is a sun. Maybe even a solar system. We are literally watching the universe build itself in real-time, one infrared photon at a time.

To stay truly updated, you should check the official STScI (Space Telescope Science Institute) gallery every few weeks. They often upload raw data and "unprocessed" versions that give a much grittier, more realistic look at what the telescope is actually seeing before the public relations teams get ahold of them. Analyzing the "raw" frames can often reveal background galaxies that didn't make the final "pretty" crop but are scientifically mind-blowing.