Let’s get one thing straight right away: James Cook didn't "discover" Australia. Honestly, the idea that a guy in a fancy coat hopped off a boat and found a continent already inhabited for 65,000 years is a bit of a stretch, right? But in the context of world history and the expansion of the British Empire, what James Cook explorer Australia efforts actually accomplished changed the map of the world forever.

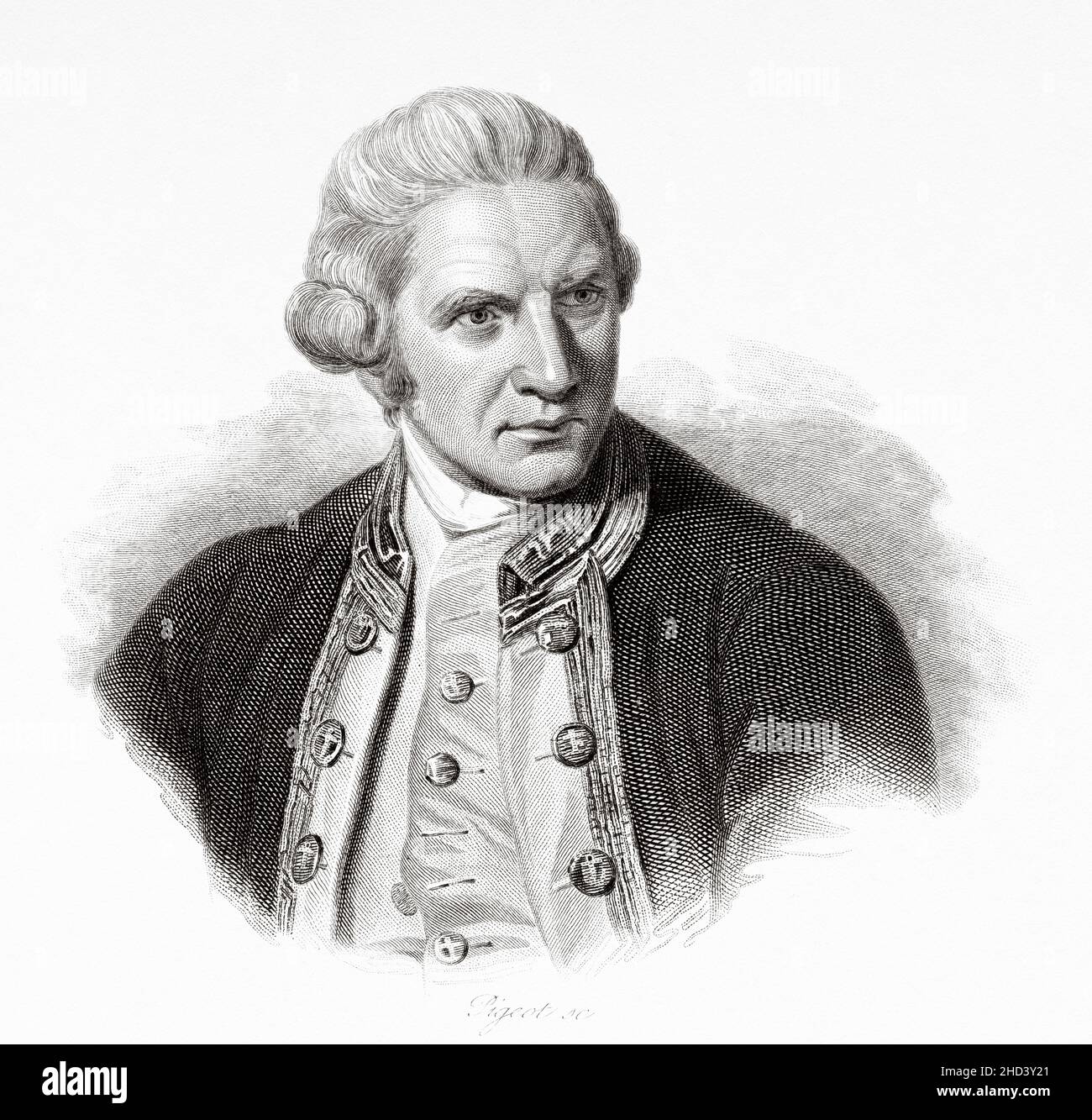

He was a farm boy. Really. James Cook wasn't born into the naval elite; he clawed his way up through the merchant navy before joining the Royal Navy as a lowly seaman. By the time he hit the coast of what we now call New South Wales in 1770, he was a master navigator with a obsession for accuracy that bordered on the pathologically intense.

The Secret Mission Behind the Transit of Venus

Most people think the HMS Endeavour headed south just to look for land. That's only half true. The official story was that Cook was sent to Tahiti to observe the Transit of Venus. Astronomers needed to measure the distance between the Earth and the Sun, and they needed data from the South Pacific to do it.

But once the telescope was packed away? Cook opened a set of "secret instructions" from the Admiralty.

These orders told him to push south and west to find the Terra Australis Incognita—the Great Unknown Southern Land. People had been theorizing about this massive continent for centuries. They thought it had to exist just to "balance" the weight of the northern continents. Cook didn't find that mythical giant, but he did stumble upon the fertile east coast of Australia, which had remained a mystery to Europeans even though the Dutch had been bumping into the dry, crunchy western side for years.

A Boat Full of Scientists and Ego

Cook wasn't alone. He had Joseph Banks on board.

Banks was a wealthy, somewhat arrogant botanist who basically funded a huge chunk of the scientific side of the trip. Imagine a floating laboratory filled with drying plants, jars of preserved fish, and artists trying to draw things they’d never seen before, like kangaroos. Banks and his team collected thousands of specimens. When they eventually landed at a place they first called Stingray Bay, they saw so many new plants that Cook crossed out the name in his journal and wrote Botany Bay instead.

It wasn't all peaceful science, though. When the Endeavour arrived at Botany Bay in April 1770, they saw two Gweagal men on the shore. The British tried to land. The Gweagal men warned them off. Cook fired muskets. It was a messy, violent first contact that set a grim tone for the next two centuries of Australian history.

The Moment Everything Almost Sunk

You've probably heard of the Great Barrier Reef. It's beautiful. It's also a death trap for 18th-century wooden ships.

On the night of June 11, 1770, the Endeavour screeched to a halt. They had hit a coral reef. Hard.

Water was pouring in. Cook, being the calm (and arguably terrifying) leader he was, ordered the crew to throw everything overboard to lighten the load. We're talking cannons, decayed ballast, oil jars—anything heavy. They even "fothered" the ship, which is basically a fancy way of saying they wrapped a sail filled with sheep dung and wool under the hull to plug the hole.

It worked.

They limped into what is now the Endeavour River (near modern-day Cooktown). They spent seven weeks there fixing the boat. This was actually a huge moment because it forced the crew to interact with the local Guugu Yimithirr people. This is where we got the word "kangaroo." The locals called the large grey macropod gangurru, and the British scribbled it down as best they could.

Possession Island and the Legal Fiction

After surviving the reef, Cook sailed further north to the tip of Queensland. On a tiny speck of land called Possession Island, he hoisted the Union Jack.

🔗 Read more: Columbia SC Weather by Month: What Most People Get Wrong

He claimed the entire eastern seaboard for King George III.

Crucially, he did this under the legal concept of Terra Nullius—land belonging to no one. Even though his own journals described seeing smoke from fires and people on the beaches all the way up the coast, the British legal system decided that since the inhabitants didn't have fences or "farms" in the European sense, the land was technically empty. This single moment is why Cook remains such a polarizing figure today. To some, he's a master mariner; to others, he's the face of a colonial invasion.

Why Cook's Maps Changed Everything

Before Cook, maps of the Pacific looked like a toddler had dropped a plate of spaghetti. There were bits of coastline here and there, mostly from Dutch explorers like Abel Tasman, but nothing was connected.

Cook’s maps were different.

- Longitude: He was one of the first to successfully use the new chronometers (basically high-tech watches) to figure out exactly how far east or west he was.

- Scurvy: He didn't lose a single man to scurvy on the first voyage. How? He forced them to eat sauerkraut and malt wort. They hated it. He had to whip some of them to make them eat their veggies, but they stayed alive.

- Coastal Detail: His charts of the Australian east coast were so accurate that some were still being used by the Royal Australian Navy well into the 20th century.

It’s hard to overstate how much of a "nerd" Cook was about his charts. He wasn't just sailing; he was surveying. Every headland, every bay, every treacherous rock was logged with mathematical precision.

Common Misconceptions About the Voyage

People get a lot of things wrong about the 1770 trip.

First off, Cook wasn't a Captain yet. He was technically a Lieutenant. He didn't get the title of Captain until later.

📖 Related: Time in Virginia Beach: What Most People Get Wrong About a Coastal Getaway

Secondly, he didn't "find" the Sydney Opera House location. He actually sailed right past the entrance to Sydney Harbour (Port Jackson). He saw it from a distance and thought it was just a "safe anchorage," naming it after George Jackson, but he never actually went inside. It wasn't until Arthur Phillip arrived with the First Fleet 18 years later that they realized it was one of the finest natural harbors in the world.

Also, the Endeavour wasn't a sleek warship. It was a "Bark." It was a refurbished coal hauler from Whitby. It was slow, sturdy, and had a flat bottom, which—ironically—is probably the only reason they survived hitting the Great Barrier Reef. A deeper, sharper warship would have tipped over and sunk immediately.

The Legacy: Hero or Villain?

If you go to a museum in London, Cook is a hero of the Enlightenment. If you talk to an Indigenous Australian in Queensland, he might be seen very differently.

The reality is nuanced. Cook himself expressed a strange kind of admiration for the Aboriginal people in his private journals. He wrote that they were "far happier than we Europeans," noting that they had no interest in the "superfluities" of Western life. Yet, his actions provided the legal framework for their dispossession.

He was a man of his time—a tool of an empire that wanted land and resources. But he was also a brilliant scientist who proved that the world was much bigger, and much more complex, than anyone in London had dared to imagine.

How to Explore the Cook Trail Today

If you want to see the history of James Cook explorer Australia for yourself, you don't need a wooden boat and a diet of fermented cabbage.

- Visit Botany Bay (Kamay Botany Bay National Park): You can stand on the exact spot where Cook landed. There are monuments, but more importantly, there are interpretive centers that explain the Gweagal perspective of that day.

- The Australian National Maritime Museum: Located in Sydney, they have a full-scale, sailing replica of the HMS Endeavour. Walking through it makes you realize how cramped and smelly the original 1770 voyage must have been. 850 square feet for 94 men. Think about that.

- Cooktown, Queensland: This is where the ship was repaired. It’s a stunning part of the country where the rainforest meets the reef. The James Cook Museum there houses the original anchor and a cannon thrown overboard in 1770, recovered by divers in the 1970s.

- The Journals: You can read Cook's actual digitized journals via the National Library of Australia. Seeing his messy handwriting and the way he crosses out words gives you a much better sense of the man than any textbook ever could.

To truly understand the impact of the 1770 voyage, you have to look at both the charts he drew and the cultures that were impacted by them. It's a story of incredible seamanship and devastating consequences, all wrapped up in one 100-foot coal boat.

Actionable Next Steps for History Buffs:

- Read the primary sources: Download the digital copies of the Endeavour journals from the National Library of Australia (Trove) to see the unedited observations of both Cook and Joseph Banks.

- Check the replica schedule: If you are in Australia, check the Australian National Maritime Museum's schedule to see when the Endeavour replica is doing coastal voyages; they often allow public tours or even "voyage crew" positions for a fee.

- Explore the Indigenous perspective: Visit the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) website to read the "First Encounters" records, which provide the essential counter-narrative to the British colonial records.