Ask a random person on the street who the greatest scientist ever was. They’ll say Einstein. Maybe Newton. If they’re feeling particularly intellectual, they might toss out Stephen Hawking or Marie Curie. But almost nobody says James Clerk Maxwell. Honestly? That’s a travesty. Without Maxwell, you wouldn’t be reading this on a screen. You wouldn’t have Wi-Fi. Your microwave wouldn’t work, and the very concept of "electronics" would be stuck in a dark age of gas lamps and carrier pigeons.

He was the guy who glued the world together.

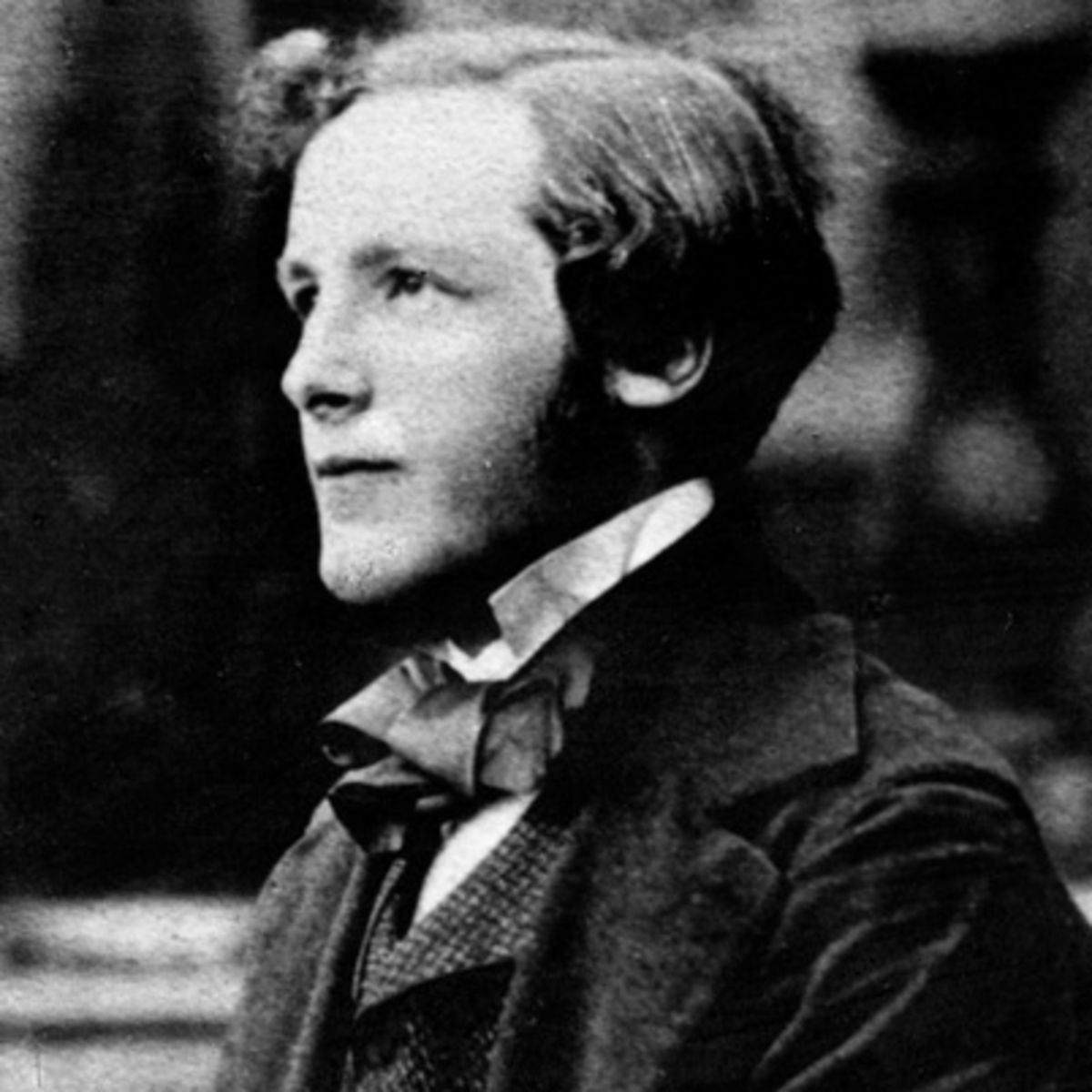

Maxwell was a 19th-century Scotsman who looked at electricity and magnetism—two things people thought were totally separate—and realized they were actually two sides of the same coin. He didn't just guess; he proved it with math so elegant it makes physicists weep. Albert Einstein once said he stood on the shoulders of Maxwell. Think about that. The guy who came up with $E=mc^2$ thought Maxwell was the real MVP.

The Scottish Polymath and the "Great Synthesis"

James Clerk Maxwell wasn’t a one-hit wonder. Born in Edinburgh in 1831, he was the kind of kid who asked "how does it work?" about everything. His neighbors called him "Dafty" because he was so distracted by his own thoughts. They were wrong. He was just busy rewriting the laws of the universe in his head.

Before Maxwell, people knew about magnets. They knew about static electricity. They even knew about light. But they thought these were distinct, unrelated phenomena. Maxwell changed everything with a set of equations—now famously known as Maxwell’s Equations. He basically looked at the messy experimental data from guys like Michael Faraday and realized that changing electric fields create magnetic fields, and vice versa.

This wasn't just a "neat" discovery. It was the birth of Classical Electromagnetism.

He predicted that these coupled fields would travel through space as waves. Then, he did the math to find out how fast those waves move. The result? 310,740,000 meters per second. He looked at that number and realized it was almost exactly the measured speed of light. That was the "Eureka" moment. He realized light itself is an electromagnetic wave. This is arguably the most significant discovery in the history of physics, ranking right up there with gravity.

📖 Related: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

Beyond the Equations: Color and Saturn’s Rings

Most people stop at the electricity stuff, but Maxwell was a bit of a restless genius. Ever wonder why your phone screen can show millions of colors using just red, green, and blue pixels? You can thank Maxwell for that, too. In 1861, he produced the world's first durable color photograph.

It was a picture of a tartan ribbon. He figured out that the human eye perceives color through three primary receptors. By taking three separate black-and-white photos through red, green, and blue filters and then projecting them together, he proved the three-color theory of vision. He basically invented the foundation for every digital display and color TV in existence.

Then there was the Saturn thing.

In the 1850s, the makeup of Saturn’s rings was a huge mystery. Were they solid? Liquid? A gas? Maxwell spent two years doing the grueling mechanical math. He proved that a solid ring would shatter and a liquid ring would clump into moons. The only way the rings could stay stable was if they were made of billions of tiny, independent particles orbiting the planet. It took over a century for the Voyager space probes to fly by and prove he was 100% correct.

The Statistical Side of Reality

Maxwell didn't just play with waves and rings; he pioneered the way we think about gases. Along with Ludwig Boltzmann, he developed the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Basically, you can't track every single molecule in a room. It's impossible. So, Maxwell used statistics to describe how they move. He showed that temperature is just the average speed of molecules bouncing around. This was the start of statistical mechanics. It was a total shift in how scientists approached reality—moving from "we can know exactly where this one thing is" to "we can predict how the whole system behaves."

👉 See also: When Can I Pre Order iPhone 16 Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

He also came up with a famous thought experiment called Maxwell's Demon. It's this weird little paradox involving a tiny creature sorting fast and slow molecules to reverse entropy. It sounds like sci-fi, but it’s still debated in thermodynamics and information theory today. It forces us to ask: can information actually affect physical reality?

Why He Isn't a Household Name

It’s kind of weird that Maxwell isn’t as famous as Newton. Maybe it’s because his work is so... mathy? You can visualize an apple falling on Newton’s head. You can visualize Einstein’s hair and his clock towers. But Maxwell’s greatest achievement is a set of partial differential equations.

They aren't "catchy."

But the reality is that James Clerk Maxwell is the bridge. He connects the classical world of Newton to the quantum world of Einstein and Planck. Without his work on electromagnetism, Einstein would have had no starting point for Special Relativity. Without his work on statistical mechanics, we wouldn't understand the behavior of matter at a fundamental level.

He died young, at just 48, from abdominal cancer. It’s wild to think about what else he would have figured out if he’d lived another thirty years. He was just getting started.

What Most People Get Wrong About Maxwell

A common misconception is that Maxwell "invented" the radio. He didn't. Heinrich Hertz was the one who actually proved electromagnetic waves existed in a lab, and Guglielmo Marconi turned it into a business. But Maxwell provided the blueprint. He told them exactly what to look for and how fast it would be going.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

Another mistake is thinking he was just a "theorist." Maxwell was a hands-on guy. He oversaw the construction of the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge. This lab went on to become the birthplace of modern physics, where the electron was discovered and the structure of DNA was eventually mapped out. Maxwell’s DNA is in every part of modern science.

The Real Legacy: Your Daily Life

If you want to appreciate Maxwell, look around your room right now.

- Your Phone: Communicates via electromagnetic waves Maxwell described.

- Your Oven: Uses the heat properties and waves he calculated.

- Your Eyes: You understand how you see color because of him.

- The Power Grid: Generators and motors work on the principles of induction he formalized.

He was a humble guy. He didn't seek fame. He spent much of his time editing the works of Henry Cavendish because he felt Cavendish deserved more credit. It’s ironic that he’s now the one who is overshadowed by others.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you’re fascinated by how the world actually works, don’t just stop at a biography. You can actually see Maxwell's influence in real-time.

- Check out the "Three-Color" principle: Open any photo editing app (like Photoshop or even a simple phone editor). Look at the RGB channels. That’s Maxwell’s 1861 tartan ribbon experiment in action.

- Look up "Maxwell’s Equations" on YouTube: Even if you aren't a math whiz, watch a visual breakdown of how a changing magnetic field creates an electric one. It’s the closest thing to real magic we have.

- Visit Edinburgh (virtually or in person): There’s a statue of him on George Street. He’s holding a color wheel and his dog, Toby. It’s a great reminder that the man who solved the universe also really liked his dog.

- Read "The Man Who Changed Everything": This biography by Basil Mahon is probably the best, most accessible deep dive into his life. It avoids the dry textbook vibe and gets into his personality—which was actually pretty funny and lighthearted.

James Clerk Maxwell was the ultimate "scientist's scientist." He didn't care about the spotlight; he just wanted to know how the gears of the universe turned. We owe him a lot more than a mention in a physics textbook. We owe him the modern world.