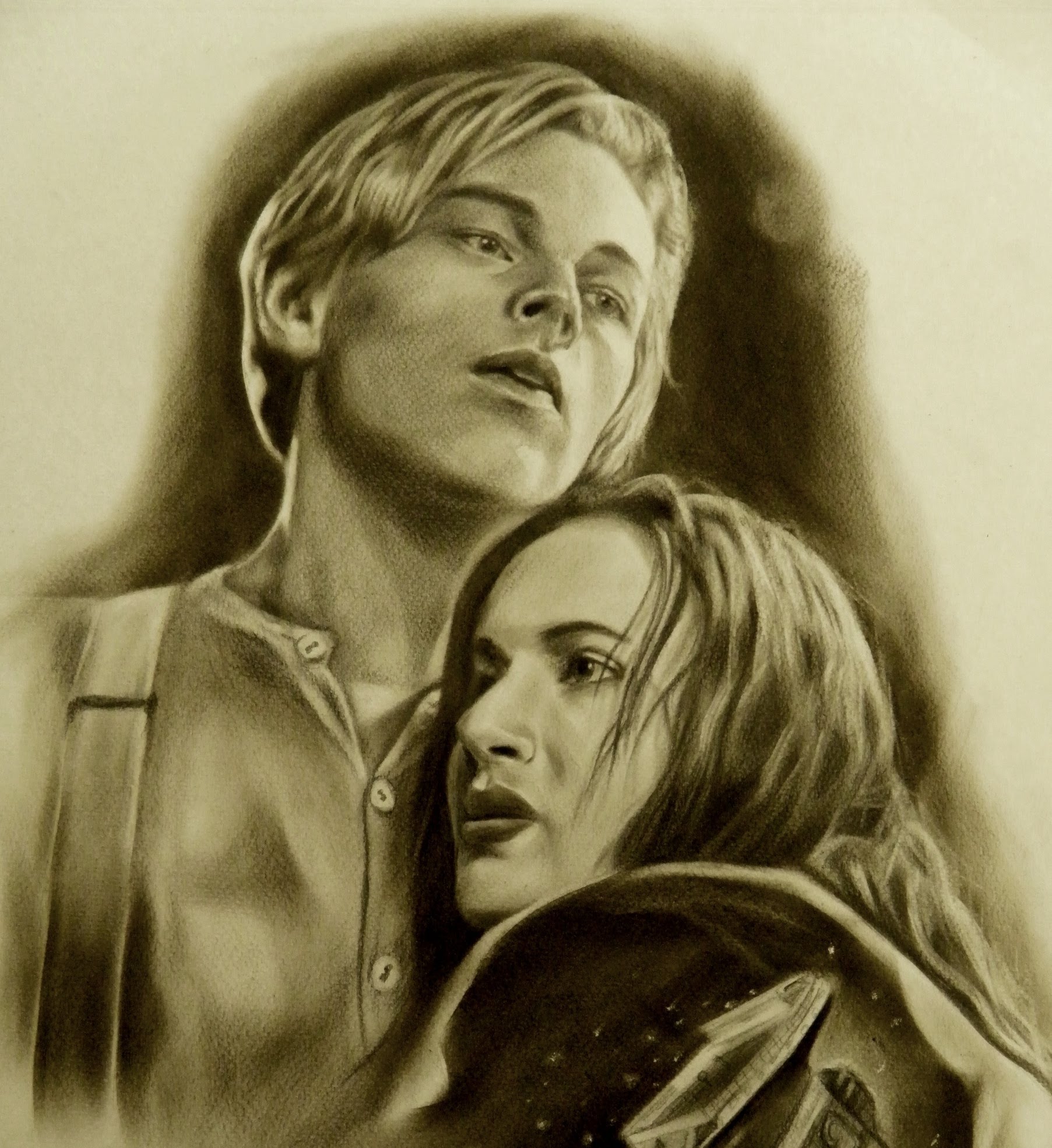

"Jack, I want you to draw me like one of your French girls."

It is probably the most quoted line in modern cinema history. When Kate Winslet reclined on that velvet sofa in James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster, she wasn't just creating a steamy movie moment; she was launching a multi-decade obsession with a piece of charcoal art. People still hunt for the actual Titanic Rose drawing today, often confusing the cinematic prop with real history or wondering if a starving artist actually sketched a socialite in a sinking cabin.

Let's get the big thing out of the way: Leonardo DiCaprio didn't draw it. He’s a brilliant actor, sure, but his sketching skills weren't what Cameron needed for the close-ups. The hands you see flying across the paper in the film actually belong to James Cameron himself. He’s a bit of a polymath, and he wanted a very specific look for the art—something that felt authentic to the 1910s but carried the emotional weight of the story.

The Man Behind the Charcoal

The mystery of the drawing usually starts with who actually held the pencil. While Jack Dawson is a fictional character, the art is very real. Cameron is a lefty, whereas DiCaprio is right-handed. If you watch the scene closely, the film is actually mirrored in those tight shots so the "drawing hand" matches Jack’s dominant side. It’s a tiny bit of movie magic that most people miss on their first fifty viewings.

The sketch isn't just a prop. It’s a character.

Honestly, the way people talk about it, you’d think it was recovered from the bottom of the Atlantic in 1912. It wasn't. There was no Rose DeWitt Bukater on the real Titanic, and there was no Jack Dawson. There was a "J. Dawson" on the manifest—Joseph Dawson—but he was a coal trimmer from Dublin, not a wandering artist with a penchant for drawing nudes. The drawing exists entirely because James Cameron wanted a visual "ticking clock" for the modern-day framing of the movie.

Where is the Sketch Now?

So, if it’s a prop, where did it go? For years, it sat in a production archive, but in 2011, it finally hit the auction block. It sold for about $16,000. An anonymous collector snagged it at a Premiere Props auction. It’s kind of wild to think that a piece of paper used for a few minutes of screen time fetched more than many authentic artifacts from the actual shipwreck.

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The drawing is dated April 14, 1912, and signed with Jack’s "JD" initials. Even though it’s "fake" in a historical sense, it has become a tangible piece of pop culture history. It’s smeared with age-appropriate distressing, meant to look like it spent eighty years in a submerged safe.

Why the Drawing Stays Rent-Free in Our Heads

Art is subjective. But the actual Titanic Rose drawing hit a specific nerve because it represented the "lost" history of the ship. We are obsessed with things that survived the debris field. When the movie shows the sketch being pulled from the mud, it mirrors the real-life recovery of leather bags, letters, and boots that actually happened during the 1980s and 90s expeditions.

The drawing symbolizes the tragedy because it’s fragile. Paper shouldn't survive a shipwreck. In the film’s logic, it survived because it was sealed in a safe, protected from the "ravenous" salt water. In reality, paper can survive if it's pressed flat in a tanned leather bag—the tannins in the leather actually help preserve the fibers by preventing the growth of bacteria. That’s how we have real letters from the Titanic today.

Common Misconceptions About the Sketch

People love a good conspiracy. I've seen forum posts claiming the drawing was based on a real sketch found in the wreckage. That’s just not true. Cameron based the style of the drawing on the works of early 20th-century artists, but the specific image was created for the script.

- Fact Check: No, the drawing isn't in a museum.

- Fact Check: Leonardo DiCaprio has never claimed to be the artist.

- Fact Check: The "Heart of the Ocean" necklace in the drawing was also a prop, based on the Hope Diamond but given a fictional backstory for the film.

The drawing is actually a testament to Cameron’s obsession with detail. He didn't just scribble something. He studied the way charcoal interacts with paper to ensure the "smudge" looked right for a piece of art that had been handled by a young man in a hurry.

The Cultural Impact of the Drawing

Think about how many times this scene has been parodied. From The Simpsons to TikTok, the "draw me" meme is everywhere. But the actual art itself is quite technically proficient. If you look at the shading on the neck and the way the hair is rendered, it’s clear Cameron has a background in illustration.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

Before he was a director, Cameron was a poster artist and production designer. He understood that the drawing needed to look "good enough" to be believable as the work of a talented prodigy, but "raw enough" to feel like it was done in a single sitting under the glow of electric lights in a stateroom.

Investigating the Real Art Recovered from the Titanic

If we look away from the movie for a second, what actual art was on the ship? There wasn't a Jack Dawson, but there were high-end pieces of art lost to the sea. The most famous was a copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which had a binding set with over a thousand gemstones.

There were also sketches and paintings belonging to passengers like Francis Millet, a renowned American painter who didn't survive the sinking. When we search for the actual Titanic Rose drawing, we are often subconsciously looking for the "lost" beauty of the Edwardian era that vanished in the North Atlantic.

The movie sketch bridges the gap between the cold, hard facts of the sinking and the romanticized version we keep in our heads. It’s a placeholder for the thousands of real items—diaries, sketches, and photos—that were actually lost.

The Value of the Prop vs. Real History

It’s a bit weird, right? You can buy a piece of real Titanic coal for about $50. You can buy a piece of wood from the grand staircase for a few hundred if you find the right auction. Yet, a drawing of a fictional woman by a famous director is worth five figures.

It shows that we value the story of the Titanic as much as the ship itself. The drawing represents the "human" element. It’s intimate. It’s one person looking at another. In a tragedy defined by massive numbers—1,500 dead, 66,000 tons of steel—the drawing narrows the focus down to two people. That’s why it matters.

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The Technical Reality of the Art

If you’re an artist, you’ve probably looked at that sketch and analyzed the technique. It’s primarily charcoal and graphite. The highlights on the skin are likely done with a kneaded eraser or a white chalk pencil.

The paper used for the prop was specifically treated to look "period." It has a certain tooth to it that catches the charcoal. When Cameron was drawing it, he had to work from photos of Winslet, as the "live" sketching on set was mostly for the cameras. The actual finished product used in the film took much longer to create than the "real-time" scene suggests.

How to Tell a Real Prop from a Fake

Because the drawing is so iconic, the market is flooded with "reproduction" prints. If you see one at a flea market claiming to be "the" drawing, it’s 100% a fake.

- Check the Signature: The original has a very specific "JD" flourish.

- Look for the Smudging: Real charcoal smudges over time if not fixed. Most reproductions are just digital prints.

- The Paper: The original prop was on a heavy, textured stock.

- The Auction Record: The only known original sold in 2011. Unless that buyer is selling it to you personally, you're looking at a copy.

The Legacy of Rose's Portrait

The actual Titanic Rose drawing changed how movies handle props. It wasn't just a "thing" held by an actor; it was a plot device that connected 1912 to 1996. It proved that a simple piece of art could be as compelling as a $200 million special effect of a ship breaking in half.

When you see the drawing at the end of the film, sitting among Rose’s photos on her nightstand, it serves as the final proof of her "unsinkable" spirit. It survived the water, the pressure, and the years. Even if it’s just a piece of paper in a movie, it represents the idea that some things—feelings, memories, or a really good sketch—are worth saving.

Actionable Insights for Titanic Enthusiasts

If you’re fascinated by the intersection of Titanic history and the 1997 film, there are several ways to engage with the "real" side of the story without falling for movie myths.

- Visit the Archives: If you want to see real paper that survived the sinking, check out the collections at the Titanic Museum Attraction in Branson or Pigeon Forge. They have real letters and postcards that were recovered from the bodies of victims or saved by survivors.

- Study Period Art: To understand what a real "Jack Dawson" might have drawn like, look up the works of Charles Dana Gibson. His "Gibson Girl" drawings defined the aesthetic that Rose was trying to break away from.

- Prop Research: For those interested in movie memorabilia, follow houses like Heritage Auctions or PropStore. They occasionally list smaller items from the production of Titanic, though the main drawing stays in a private collection for now.

- Learn the Technique: If you want to recreate the look, practice "chiaroscuro" with vine charcoal. It’s all about the contrast between deep shadows and bright light, which is exactly what Cameron used to make the sketch pop on screen.

The drawing might be a work of fiction, but the emotions it stirs up are about as real as it gets. It serves as a reminder that behind the "unsinkable" steel and the massive tragedy, there were individuals with stories, faces, and perhaps even their own secret sketches tucked away in leather suitcases.