James Baldwin was angry. Actually, that’s an understatement. He was vibrating with a kind of precise, analytical rage that most of us couldn't hope to articulate on our best days. When you sit down to read the notes of a native son essay, you aren't just reading a piece of mid-century literature. You're walking into a room where the air is thick with the scent of funeral flowers and the literal smoke of the 1943 Harlem riot. It’s heavy stuff. Honestly, if you’ve ever felt like your identity was being squeezed into a box that didn't fit, Baldwin is talking directly to you.

The essay is the title piece of his 1955 collection. It’s basically a memoir, but it’s also a philosophical surgical strike. Baldwin writes it while reflecting on the death of his father—a man he describes as "bitter" and "chilled"—which happened right as the world was tearing itself apart. Imagine burying your father on your 19th birthday while a race riot is breaking out down the street. That’s the backdrop. It’s messy. It’s violent. And it’s incredibly human.

The Father, the Son, and the Ghost of Bitterness

The core of the notes of a native son essay is this complicated, almost suffocating relationship between Baldwin and his stepfather, David Baldwin. David was a preacher. He was also a man consumed by a "terrible disease" of the spirit. Baldwin realizes, with a kind of dawning horror, that the same bitterness that destroyed his father is starting to take root in him too. It’s scary.

He tells this story about a waitress in New Jersey. Baldwin had been working in a defense plant, dealing with constant Jim Crow exclusions. One night, he goes into a diner called "The American Diner," and the waitress tells him, "We don't serve Negroes here." Baldwin doesn't just walk out. He snaps. He throws a water mug at her. It misses and shatters a mirror, and he barely escapes with his life as a mob starts to form.

That moment is the turning point of the essay. He realizes that his hatred made him lose control. It made him a "native son" of a system that was designed to break him. He writes that his life was in danger not because of the mob, but because he had allowed his heart to become as "poisoned" as his father’s. You see, the notes of a native son essay isn't just about racism in a systemic sense; it’s about the psychological toll of living in a world that refuses to see you.

Why the 1943 Harlem Riot Matters Here

While Baldwin is mourning, Harlem is burning. The riot was sparked by the shooting of a Black soldier, Robert Bandy, by a white police officer. To Baldwin, the riot felt inevitable. He describes the "smashing of glass" as a sound that was "singularly satisfying." That's a bold thing to say, right? But he’s being honest. He explains that the destruction wasn't just about one incident; it was the physical manifestation of a fever.

📖 Related: Defining Chic: Why It Is Not Just About the Clothes You Wear

The timing is everything.

Father's death.

Son's birthday.

The city on fire.

Baldwin uses these overlapping events to show that the personal and the political are the same thing. You can't separate his father’s private misery from the public misery of Harlem. They feed each other. It’s a cycle.

Breaking Down the "Native Son" Concept

Wait, why the title? If you’re a book nerd, you know Richard Wright wrote Native Son in 1940. Baldwin was actually a protégé of Wright’s, but they had a massive falling out. Baldwin thought Wright’s character, Bigger Thomas, was a caricature. He felt that by making Bigger a mindless killer driven only by fear, Wright was playing into the very tropes he was trying to critique.

In his notes of a native son essay, Baldwin is reclaiming that title. He’s saying, "I am a native son, but I am complicated." He’s insisting on his own humanity. He refuses to be just a victim or just a rebel. He’s a writer, a son, a Black man, and an American—all at once. This tension is what makes the essay feel so modern. We are still having these exact conversations about "representation" and whether characters of color are allowed to be flawed without being "problematic."

People often get Baldwin wrong. They think he was just a "civil rights writer." He was so much more. He was a stylist. His sentences are long, winding things that loop back on themselves, sort of like a jazz solo. He’ll start with a simple observation about a funeral and end up questioning the entire foundation of Western civilization.

👉 See also: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

- He explores the "dread" of being a Black man in white spaces.

- He examines the "insupportable" burden of his father’s legacy.

- He looks at the "theatre" of race relations in the North versus the South.

One of the most famous lines in the notes of a native son essay is about how he must hold two ideas in his head at once. First, the acceptance of life as it is, which is often brutal and unfair. Second, the absolute refusal to accept injustice. It’s a paradox. It’s exhausting. But Baldwin argues it’s the only way to stay sane.

The New Jersey Incident: A Lesson in Self-Preservation

Let’s go back to that water mug in the diner. Baldwin writes that after he threw it, he felt a "sense of release." But that release was followed by a crushing realization. He saw that he was prepared to kill—and be killed—over a cup of coffee. He writes, "I saw that I had been ready to commit murder."

This is the E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness) moment of the essay. Baldwin isn't preaching from a mountaintop. He’s admitting he was down in the dirt. He’s admitting he was "part of the thing" he hated. That kind of vulnerability is why we still read him. Most writers want to look like the hero. Baldwin is okay with looking like a terrified 19-year-old who almost threw his life away because he couldn't take the silence of a waitress anymore.

How to Apply Baldwin’s Logic Today

So, you’ve read the notes of a native son essay, or you’re about to. What do you do with it? It’s not just a history lesson. It’s a blueprint for emotional survival.

First, stop trying to simplify your feelings about your heritage or your parents. Baldwin loved his father and hated him. He felt American and felt totally alienated by America. Those things can both be true. Embracing the "and" instead of the "or" is a very Baldwin move.

✨ Don't miss: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

Second, watch out for the "poison." Baldwin’s main takeaway is that hatred is a luxury you can't afford because it consumes the vessel it’s stored in. If you spend all your time reacting to the world's ugliness, you lose the ability to create your own beauty. It’s a tough pill to swallow, especially when the world is legitimately messed up.

Practical Steps for Engaging with the Text

- Read it out loud. Seriously. Baldwin’s rhythm is half the point. If you don't hear the cadence, you're missing the soul of the piece.

- Look up the 1943 Harlem riot. Understanding the specific geography of Lenox Avenue and the background of the Bandy shooting makes the "atmosphere" Baldwin describes much more vivid.

- Journal about your own "inherited" traits. What did your parents pass down to you that you’re trying to shake off? Baldwin spent his whole life trying not to become his father, only to realize he had to understand his father to understand himself.

- Don't rush. This isn't a "skim and win" type of essay. It’s dense. It’s supposed to make you feel a little uncomfortable.

The notes of a native son essay ends with a call to "keep the heart free of hatred and despair." It sounds a bit like a Hallmark card when you put it like that, but in the context of Baldwin’s life, it’s a radical, militant act of self-preservation. He’s saying that staying human in an inhuman system is the ultimate form of resistance.

Honestly, Baldwin’s work is more relevant now than it was in the fifties. We live in an era of "hot takes" and 280-character outbursts. Baldwin didn't do hot takes. He did deep, agonizing excavations of the soul. If you want to understand the American psyche—and your own place in it—you have to grapple with this text. It’s not optional. It’s the groundwork.

The next time you feel that rising heat in your chest when you see something unfair, think about the shattered mirror in that Jersey diner. Think about the "native son" who chose to pick up a pen instead of another mug. That’s where the real power is.

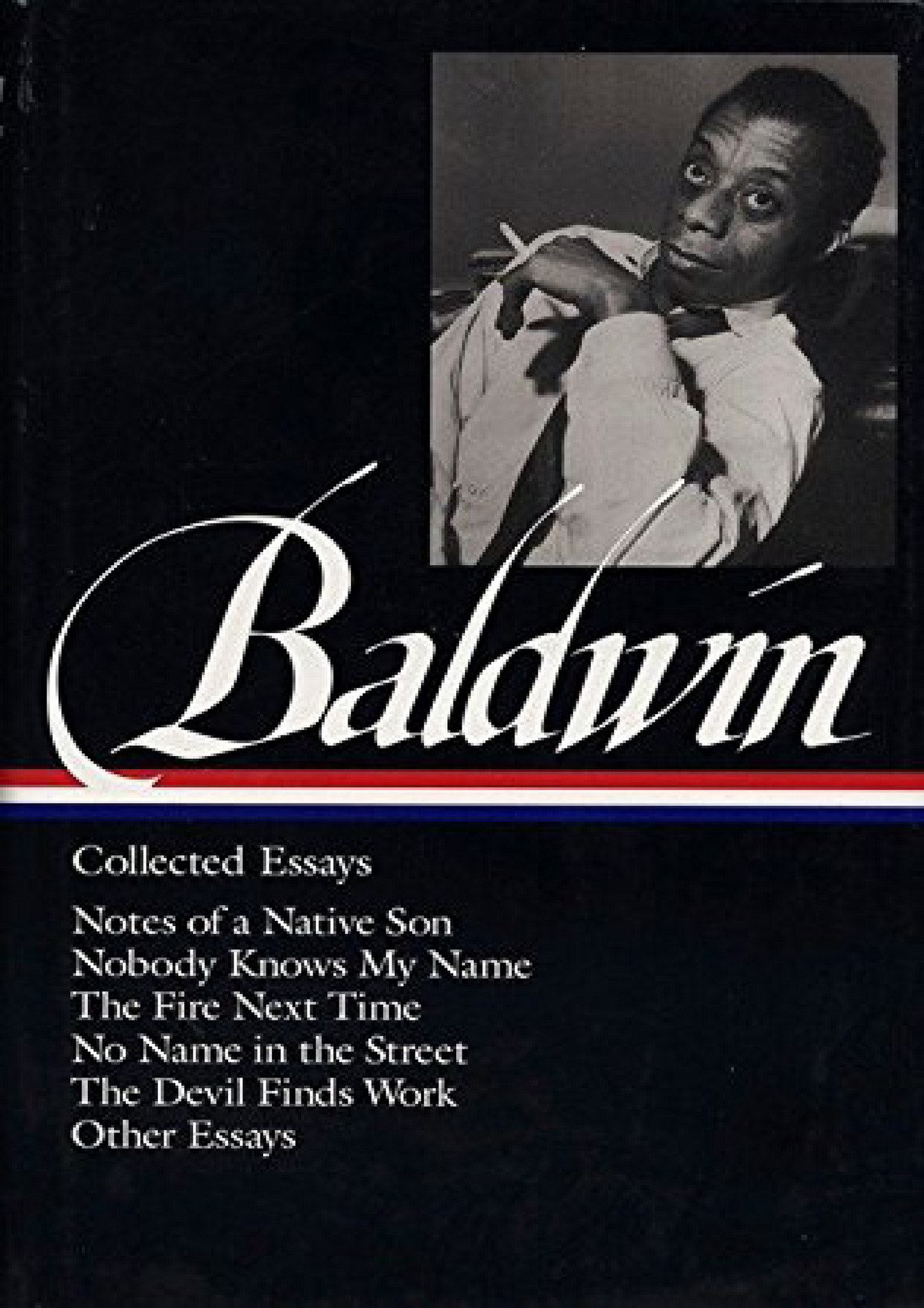

To truly grasp the weight of Baldwin’s arguments, your next move should be to compare this essay with his later work, specifically The Fire Next Time. You’ll see how his "precise rage" evolved into a prophetic warning for the entire nation. Start by highlighting the sections in Notes where he discusses the "necessity" of the white man’s presence in his psychological landscape—it’s a challenging read that will change how you view modern social dynamics.