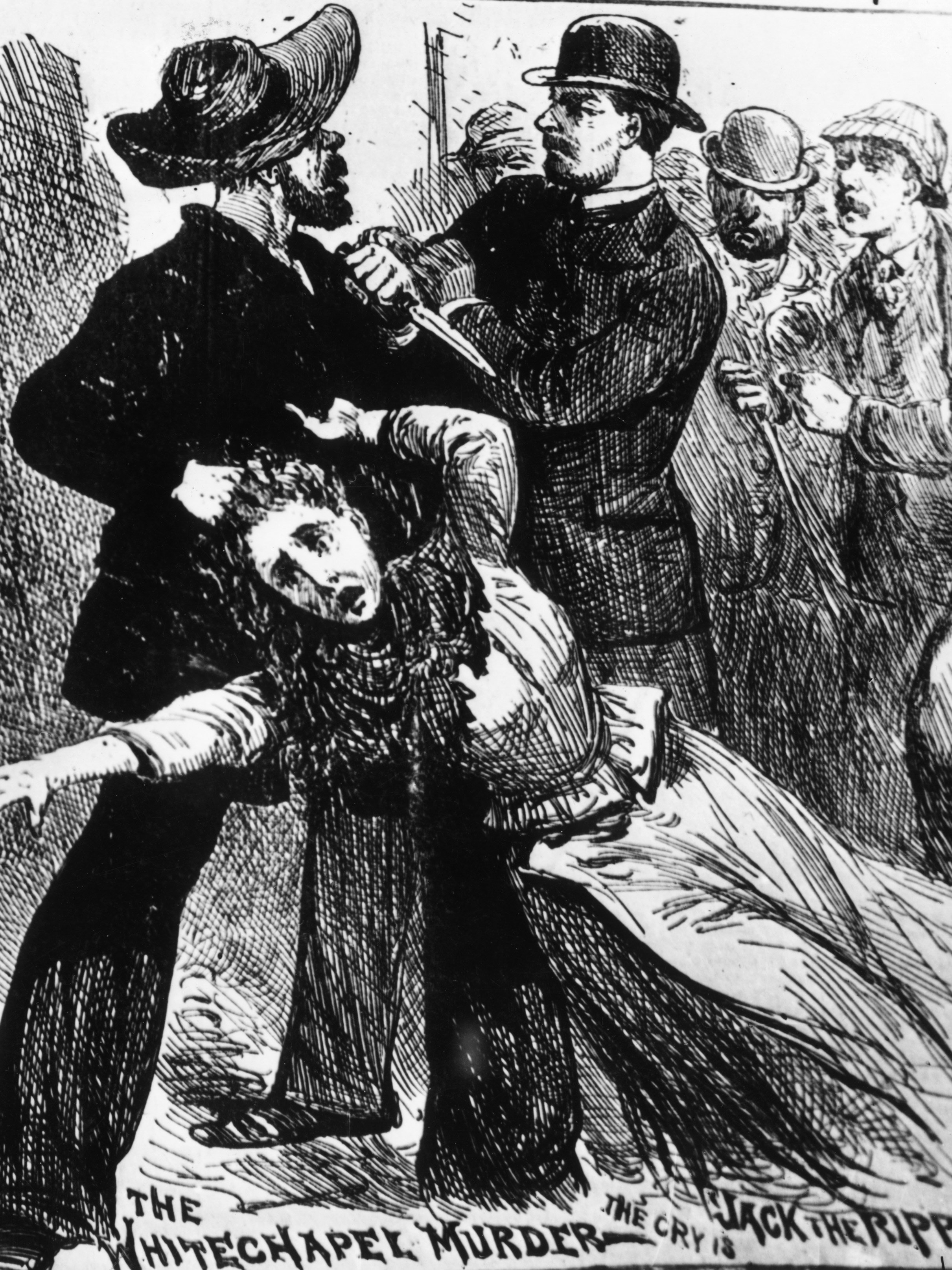

He’s the world’s most famous ghost. You know the image: a tall man in a top hat, clutching a black medical bag, vanishing into the thick London fog. But honestly? Most of that is just theater. The real story of Jack the Ripper isn't about a caped villain. It’s about a series of brutal, unsolved murders in the autumn of 1888 that changed how we look at crime forever.

If you’ve ever wondered why we are still talking about a killer from 137 years ago, you're not alone. It’s basically the ultimate "cold case." The Whitechapel murders weren't just crimes; they were a media circus that exposed the rotting underbelly of Victorian London.

Who Was Jack the Ripper?

The name itself is a bit of a trick. It didn't come from the police. It came from a letter. In late September 1888, the Central News Agency received a taunting note signed "Jack the Ripper." Most modern experts, or "Ripperologists," think that letter was a hoax written by a journalist to sell more papers. It worked. The name stuck, and a faceless killer became a global legend.

Basically, "Jack the Ripper" is the pseudonym given to an unidentified serial killer who operated in the Whitechapel district of London’s East End. Between August and November 1888, he (or she, though most assume a male) killed at least five women. These women are known as the "Canonical Five."

The Women Who Lost Their Lives

For a long time, history ignored the victims. They were just "prostitutes" in the eyes of the Victorian public. But recent research, especially by historian Hallie Rubenhold in her book The Five, shows that isn't the whole truth. These women were mothers, daughters, and wives who had fallen on incredibly hard times.

- Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols: Found on August 31 in Buck's Row. She was 43 and had five children. On the night she died, she was out on the street because she didn't have the "fourpence" needed for a bed in a lodging house.

- Annie Chapman: Found on September 8. She was 47. Her life had spiraled after the death of her daughter and a divorce fueled by alcoholism.

- Elizabeth Stride: Killed on September 30. Unlike the others, her throat was cut but her body wasn't mutilated. People think the Ripper was interrupted.

- Catherine Eddowes: Also killed on September 30, just an hour after Stride. This is the "Double Event."

- Mary Jane Kelly: The youngest and the only one killed indoors, on November 9. Her murder was the most gruesome because the killer had the privacy of her room in Miller's Court.

Whitechapel back then was a nightmare. It was overcrowded, filthy, and smelled of slaughterhouses and open sewers. If you were poor, you lived in "doss houses" where you paid for a bed by the night. If you couldn't pay, you walked the streets. That’s where the killer found them.

The Suspects: Who Actually Did It?

Police at the time were totally out of their depth. They didn't have DNA. They didn't have fingerprinting. They barely had a functioning detective department. They interviewed thousands of people, but they never caught him.

Some of the "classic" suspects are honestly pretty wild. There’s Montague Druitt, a barrister who died by suicide shortly after the last murder. Then there’s Michael Ostrog, a Russian con man and physician. Many people even point to Prince Albert Victor, the grandson of Queen Victoria, though that’s mostly a conspiracy theory with zero evidence.

The DNA Breakthrough (Sorta)

In recent years, a lot of buzz has surrounded Aaron Kosminski. He was a Polish barber who lived in Whitechapel and was a prime suspect for the police back in 1888. In 2014 and again in 2019, researcher Russell Edwards claimed that DNA from a shawl belonging to Catherine Eddowes linked Kosminski to the crime.

👉 See also: The French Wars of Religion: What Really Happened During Europe's Bloodiest Family Feud

Is the case closed? Not really. Many scientists argue the shawl was contaminated after over a century of being handled. It’s a "maybe," but in the Ripper world, nothing is ever 100%.

Why It Still Matters Today

The Ripper case was the birth of the modern serial killer obsession. It was the first time a "faceless" killer used the media to taunt the public. It forced the wealthy people in London to look at the poverty in the East End.

It also changed how we investigate crimes. The failure to catch Jack led to better forensic techniques, the use of photography at crime scenes, and the development of criminal profiling.

What You Should Know If You're Interested

If you want to look into this further, don't just watch the movies. Most of them—like From Hell—are fun but totally inaccurate.

- Read the primary sources: Look at the "Dear Boss" letter and the "From Hell" letter (which came with half a preserved human kidney).

- Focus on the victims: Understanding the lives of these five women tells you more about the era than the killer ever could.

- Visit the sites (carefully): You can still walk the streets of Spitalfields and Whitechapel. Most of the original buildings are gone, but the vibe of the alleys is still there.

The mystery of Jack the Ripper probably won't ever be solved with a smoking gun. But by studying the case, we learn about the failures of the past and how far we've come in seeking justice for those who usually get forgotten.

To get a real sense of the timeline, you should look up the map of the Whitechapel Murders. Seeing how close together these crimes happened—all within a one-mile radius—really puts the terror of 1888 into perspective. It wasn't a sprawling hunt; it was a neighborhood being stalked. For your next step, try searching for the "Whitechapel Murders file" at the National Archives to see the actual police notes from the 1880s.