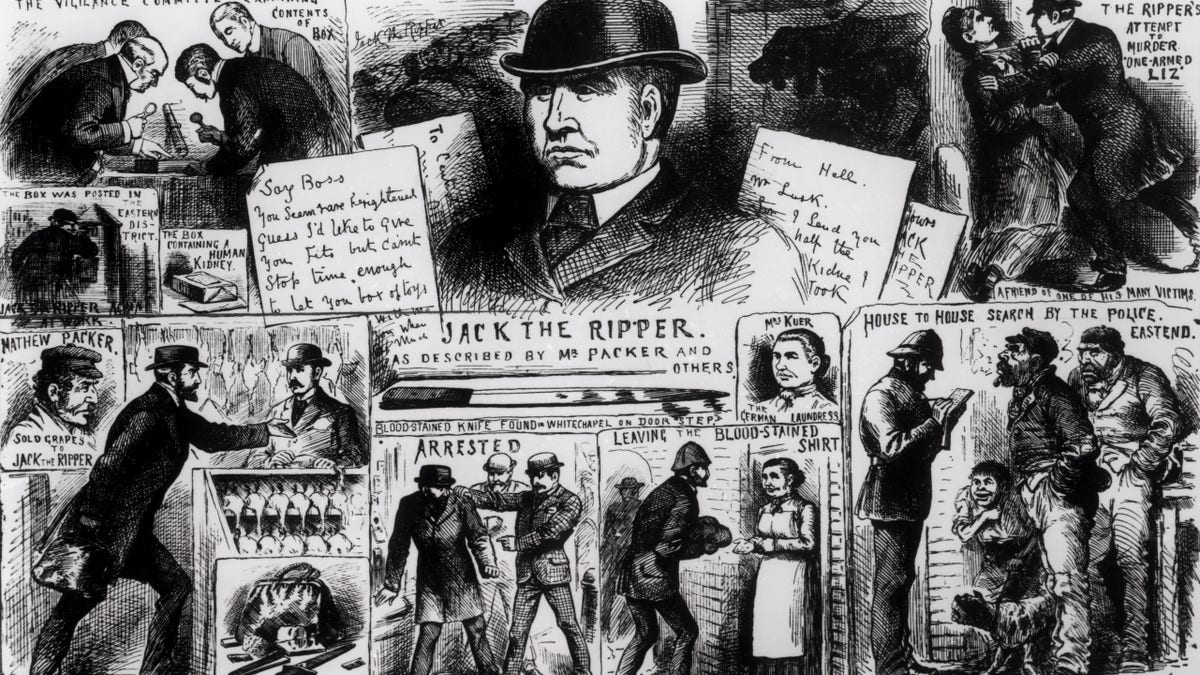

Honestly, the internet is a messy place when you start digging into Victorian true crime. You've probably seen them—the grainy, black-and-white images that pop up the moment you search for 1888 Whitechapel. Most people think they’re looking at a complete gallery of the Ripper’s work. They aren't.

There is a huge difference between a "crime scene photo" and a "mortuary photo," and in the case of the Whitechapel murders, the distinction changes everything we know about how the police actually worked back then. For over a century, jack the ripper murder photos have fueled theories, nightmares, and a fair amount of flat-out misinformation.

Let's be real: forensics in 1888 was basically a guy with a notebook and a prayer. Photography was just starting to crawl out of the studio and into the streets, and the "Ripper" case was the awkward, bloody testing ground for it.

The Only Real Crime Scene Photo

If you see a photo of a body in situ—meaning, exactly where it was found—it is almost certainly Mary Jane Kelly.

She was the fifth "canonical" victim, murdered in her room at 13 Miller’s Court on November 9, 1888. Because she was found indoors, the police actually had the luxury of time. They didn't have to worry about a crowd of 2,000 angry East Enders pressing against a wooden fence while they worked.

🔗 Read more: Trump vs Harris Polls Swing States: What Most People Get Wrong

The image of Kelly is harrowing. It’s also a technical miracle for the time. This was one of the first instances of a camera being used to document a murder scene before the body was touched. The photographer had to use magnesium powder flash—a literal explosion of light—to get any detail in that dark, cramped room.

Every other "murder photo" you see of the canonical five? Those were taken at the mortuary.

Why the Other Photos Look So Different

When Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, and Catherine Eddowes were found, the priority wasn't "documenting the scene." It was "get this body off the street before a riot starts."

The Victorian police were terrified of the public. In the cases of Nichols and Chapman, the bodies were moved to the local workhouse infirmary or mortuary, stripped, and washed before a photographer even showed up. This is why many of the photos show the victims propped up or lying on a slab, sometimes with their wounds crudely stitched by a surgeon for the inquest.

Take Catherine Eddowes, for example. There are actually several photos of her. One is a full-body shot at the Golden Lane Mortuary, and another is a close-up of her face. These weren't for "CSI" style analysis; they were for identification. The police often used these photos to show to the public, hoping someone would recognize the deceased.

The Photographers Behind the Lens

We actually know who some of these guys were. Joseph Martin is a name that comes up a lot. He was a freelance photographer in East London who basically became the "on-call" guy for the Metropolitan Police.

It’s kinda wild to think about. There was no official "Forensics Department." If a body turned up, the police just sent a runner to the local photo shop. "Hey Joseph, got another one for you."

Where the Originals Live Now

A lot of people think these photos are hidden in some secret "Black Museum" vault. While the Metropolitan Police's "Crime Museum" (formerly the Black Museum) does hold some artifacts, the real paper trail is at the National Archives in Kew.

🔗 Read more: Minnesota Braces for Potential First Winter Storm Next Week: What Most People Get Wrong

Specifically, look for the MEPO files. MEPO 3/140 is the big one. It contains the official police reports and some of the surviving photographs.

However, a lot of the original 1888 material is gone. Between the London Blitz and decades of "souvenir-taking" by police officers (basically, guys just slipping photos into their pockets as keepsakes), the archive is surprisingly thin. In 1987 and 1988, some of these "lost" items—including the famous "Dear Boss" letter—were actually returned anonymously to Scotland Yard.

The Myths You Should Stop Believing

You’ll often see a photo of a young, attractive woman in a Victorian dress labeled as "Mary Jane Kelly" or "Annie Chapman."

Almost 100% of the time, those are fake.

There are no known photos of any of the victims while they were alive, with one possible exception: a photo that might be Annie Chapman, which surfaced via her descendants. For the rest, we only have descriptions from friends and family. Mary Kelly was described as "Fair Emma" or "Ginger," but we have no pre-mortem image to prove what she really looked like.

The Retinal Image Theory

This is my favorite weird bit of Ripper lore. In 1888, some people—including some police officials—genuinely believed in "optography." The idea was that the last thing a person sees is "burned" into their retina like a camera film.

👉 See also: Andrea Mitchell NBC News: Why She Really Stepped Away from the Anchor Desk

They actually tried this on some of the Ripper victims. They took high-detail photos of their eyes, hoping to see the face of the killer.

Spoiler: It didn't work. Physics doesn't work that way.

Actionable Insights for Researching the Ripper

If you're diving into this, don't just trust a Google Image search. Here is how to actually verify what you're looking at:

- Check the Background: If the body is on a bed in a room, it's Kelly. If it's on a clean wooden table or a stone slab, it's a mortuary photo of someone else.

- Look for the "MEPO" Stamp: Authentic copies of the jack the ripper murder photos often carry the stamp of the Metropolitan Police or the National Archives.

- Cross-Reference with Inquest Records: The wounds shown in the photos should match the surgical descriptions in the transcripts. For instance, the specific facial mutilations on Catherine Eddowes are very distinct and match the City of London Police records perfectly.

- Use Reputable Archives: Sites like Casebook: Jack the Ripper or the Whitechapel Society have spent decades vetting these images. If they say a photo is a "later illustration" or a "re-enactment," believe them.

The fascination with these images isn't just about the gore. It’s about the fact that they are some of the only tangible links we have to five women whose lives were much more than just their endings. When you look past the shock value, you're looking at the very birth of modern criminal investigation.

To further your research, you can access the digitised versions of the Whitechapel Murders files through the UK National Archives website by searching for the "MEPO 3" series. Detailed analysis of the medical evidence can be found in Dr. Bond's original autopsy notes, which are often cited in forensic history textbooks regarding the evolution of profiling.