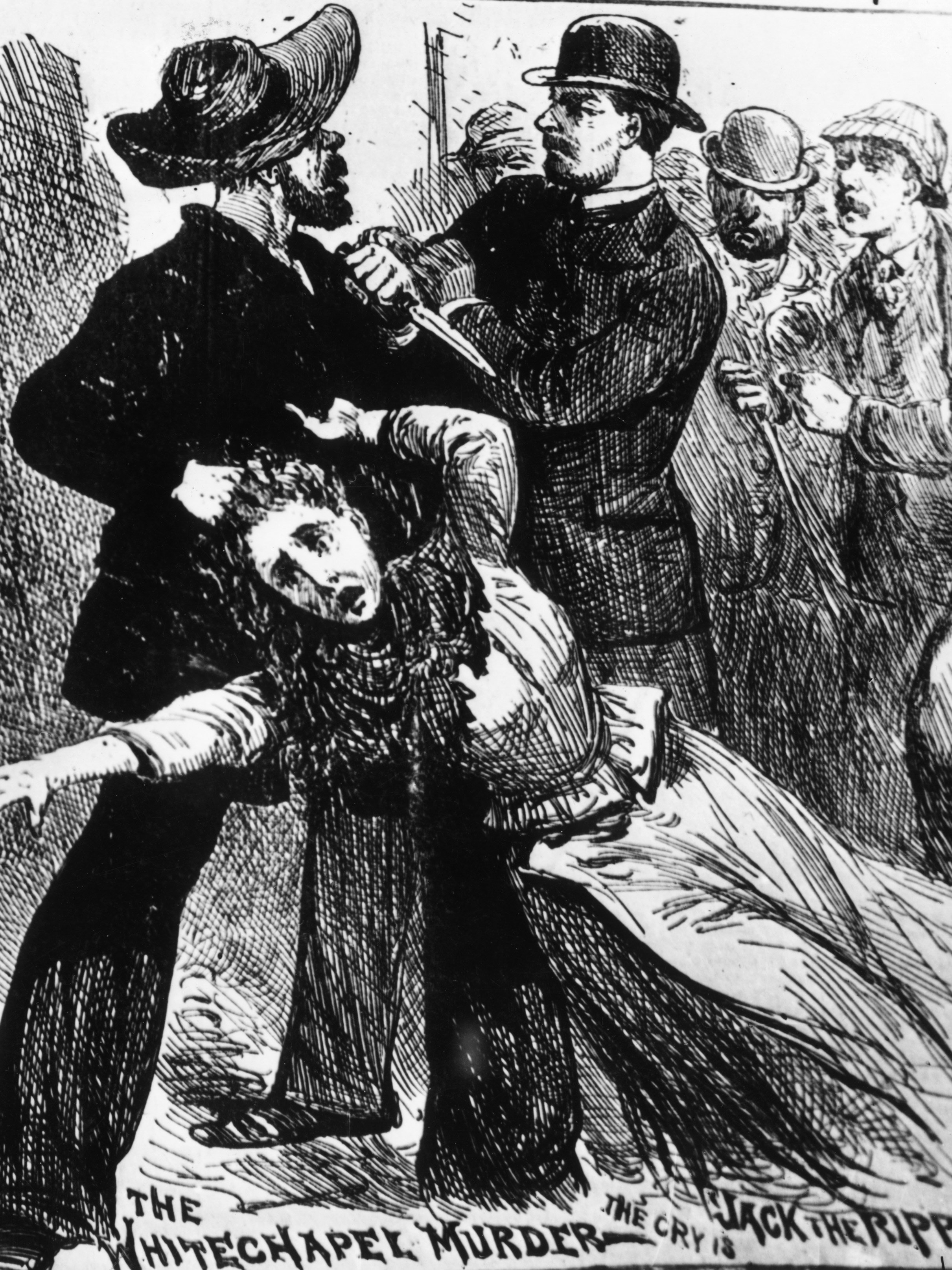

He’s the ultimate ghost story. A man in a top hat, clutching a black medical bag, vanishing into the London fog. Honestly, though? That image is mostly fiction.

Jack the Ripper wasn't a movie monster. He was a real person who tore through the East End in 1888, leaving a trail of bodies that changed how we look at crime forever. But here is the thing: almost everything you think you know about him is probably a mix of Victorian tabloid hype and Hollywood imagination. People still argue about his identity today. In 2026, the obsession hasn't cooled down. If anything, new DNA tech and historical digging have only made the mystery weirder.

The Reality of the "Canonical Five"

Most people think this guy killed dozens of women. In reality, the "canonical five" are the only ones most experts, like the late Philip Sugden, agree were definitely his work. It started with Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols in August 1888. Then came Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and finally, the horrific scene of Mary Jane Kelly in November.

💡 You might also like: Why Comedy Feel Good Movies Are Actually Getting Harder To Find

Some researchers, like those contributing to Casebook: Jack the Ripper, argue the list should be longer. Martha Tabram, for instance, was stabbed 39 times just weeks before Polly Nichols was found. Was she a "warm-up"? Or was it a different killer entirely? The wound patterns were different. No throat-slitting. No organ removal. It’s these tiny, grisly details that keep "Ripperologists" up at night.

The victims weren't just "prostitutes" in the way we think of the word now. They were women trapped in extreme poverty. They were mothers and sisters.

Mary Jane Kelly was only 25.

She died in her own bed, the only victim killed indoors. The others were found in backyards or dark alleys, often just minutes after a policeman had walked past on his beat. The speed was incredible. It’s what led the Victorian press to believe the killer had surgical skill. He knew where the organs were. He could find them in the dark.

The Suspects: Who Was Actually Under the Knife?

If you go to Whitechapel today, tour guides will give you a dozen different names. Every few years, a "definitive" book comes out claiming the case is closed.

It never is.

Aaron Kosminski: The DNA Favorite?

Recently, a lot of heat has been on Aaron Kosminski, a Polish barber who lived in the heart of the murder zone. In 2014, and again with refined testing in 2019 and 2024, researcher Russell Edwards claimed DNA from a silk shawl belonging to victim Catherine Eddowes pointed directly to Kosminski.

Sounds like a slam dunk, right? Not really.

Many scientists, including those skeptical of Dr. Jari Louhelainen’s methods, point out the shawl has been handled by thousands of people over 130 years. Contamination is a nightmare. Plus, Kosminski was known to be mentally ill and "harmless" according to some contemporary reports. Does a "harmless" man become a surgical butcher? Maybe. But the evidence is still thin.

The "Royal" Conspiracy

Then you have the wild theories. Prince Albert Victor, the grandson of Queen Victoria. People love the idea of a royal cover-up. It makes for a great movie, like From Hell. But there’s a problem. He wasn't even in London for most of the murders. He was in Scotland. Unless he had a teleportation device, he's off the hook.

Walter Sickert: The Artist's Guilt

The novelist Patricia Cornwell spent millions trying to prove the painter Walter Sickert was the Ripper. She focused on his "Camden Town Murder" paintings, which look suspiciously like Ripper crime scenes. She even claimed to find his DNA on the famous "Ripper letters."

The art world hated it.

Most historians think she’s wrong. Sickert was likely just obsessed with the murders, like everyone else in London. He might have even written some of the letters as a sick joke. That doesn't make him a serial killer. It just makes him a creep.

Why We Still Can’t Let Go

Why do we care? It’s been over a century. Everyone involved is long dead.

Basically, the Ripper case was the birth of the modern media circus. The name "Jack the Ripper" wasn't even real. It came from the "Dear Boss" letter, which most experts now believe was written by a journalist named Tom Bulling to sell more newspapers. It worked. Circulation went through the roof.

The police were overwhelmed. They didn't have fingerprints. They didn't have blood typing. They were literally wandering around in the dark with lanterns.

"I'm not a butcher, I'm not a Yid, nor yet a foreign skipper, but I'm your own light-hearted friend, yours truly, Jack the Ripper."

That’s from a postcard sent at the time. The killer—or a very talented troll—was taunting them. It created a blueprint for every serial killer mystery that followed.

What Most People Get Wrong

You’ve probably heard that the Ripper was a gentleman. High society. Top hat and cape.

The truth? He was likely a local. Someone who blended in.

Whitechapel was a labyrinth of "rookeries"—slums so dense the police were afraid to go in. If you were a stranger in a silk cape, you’d stand out like a sore thumb. The Ripper likely looked like every other laborer or butcher on the street. He was "invisible" because he belonged there.

Also, the "fog" we see in movies? That was actually "pea-souper" smog from coal fires. It was yellow, thick, and smelled like rotten eggs. It wasn't romantic. It was suffocating.

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you're looking to dive deeper into what Jack the Ripper actually was without the Hollywood fluff, start with primary sources.

- Read the Inquest Testimony: Don't trust the blogs. Look at the actual statements from the doctors who performed the autopsies. Their descriptions of the "surgical" precision vary wildly.

- Study the "From Hell" Letter: Unlike the "Dear Boss" letter, this one came with half a human kidney. It’s arguably the only communication that might be authentic.

- Visit the Archives: The National Archives in Kew holds the original "MEPO" (Metropolitan Police) files. Seeing the actual handwritten notes from Inspector Abberline changes your perspective.

- Check the Maps: Look at the Goad’s Insurance maps from 1888. You’ll see just how close these murders were. Most happened within a few hundred yards of each other.

The Ripper didn't just kill five women. He exposed the rot of Victorian society—the poverty, the failed policing, and the hunger for sensationalism. We don't need to know his name to understand the shadow he cast. Whether he was a barber, a sailor, or a mad doctor, he remains the world's most enduring "what if."

💡 You might also like: Chris Stapleton Traveller Vinyl Record: Why This Modern Classic Still Sounds Best on Wax

Focus on the victims’ stories to get a true sense of the era. Their lives tell us more about 1888 than the killer ever could. Compare the police reports to the newspaper sensationalism of the time to see how a "man" became a "legend."