You’ve probably seen the movie. You’ve seen the wide-brimmed hat, the gaunt face, and the haunted eyes of Cillian Murphy staring into the middle distance. But the real story of the father of the bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer, is way messier than a three-hour Hollywood epic can actually capture. Most people think of him as this tortured genius who lived in a vacuum of high-level physics and regret. Honestly? He was a chain-smoking polymath who read Sanskrit for fun and somehow managed to herd a group of the world's most temperamental egos into a secret city in the middle of the New Mexico desert.

Los Alamos wasn't just a lab. It was a pressure cooker.

Before he became the father of the bomb, Oppenheimer was known for being brilliant but also kind of a disaster in a laboratory setting. He was a theoretical guy through and through. In fact, his early days at Cambridge were marked by a weird incident where he allegedly left a poisoned apple on his tutor’s desk. He struggled with deep bouts of depression. He was a man of contradictions—someone who loved the desert and the stars but ended up creating something that could effectively blot them out.

Why the Father of the Bomb Still Matters in 2026

We are living in a second atomic age, basically. With AI, quantum computing, and the renewed chatter about tactical nukes in global politics, the "Oppenheimer moment" feels less like a history lesson and more like a warning. The term father of the bomb isn't just a dusty title. It represents the specific point in human history where our ability to destroy surpassed our ability to understand why we should stop.

It’s about the ethics of "can" versus "should."

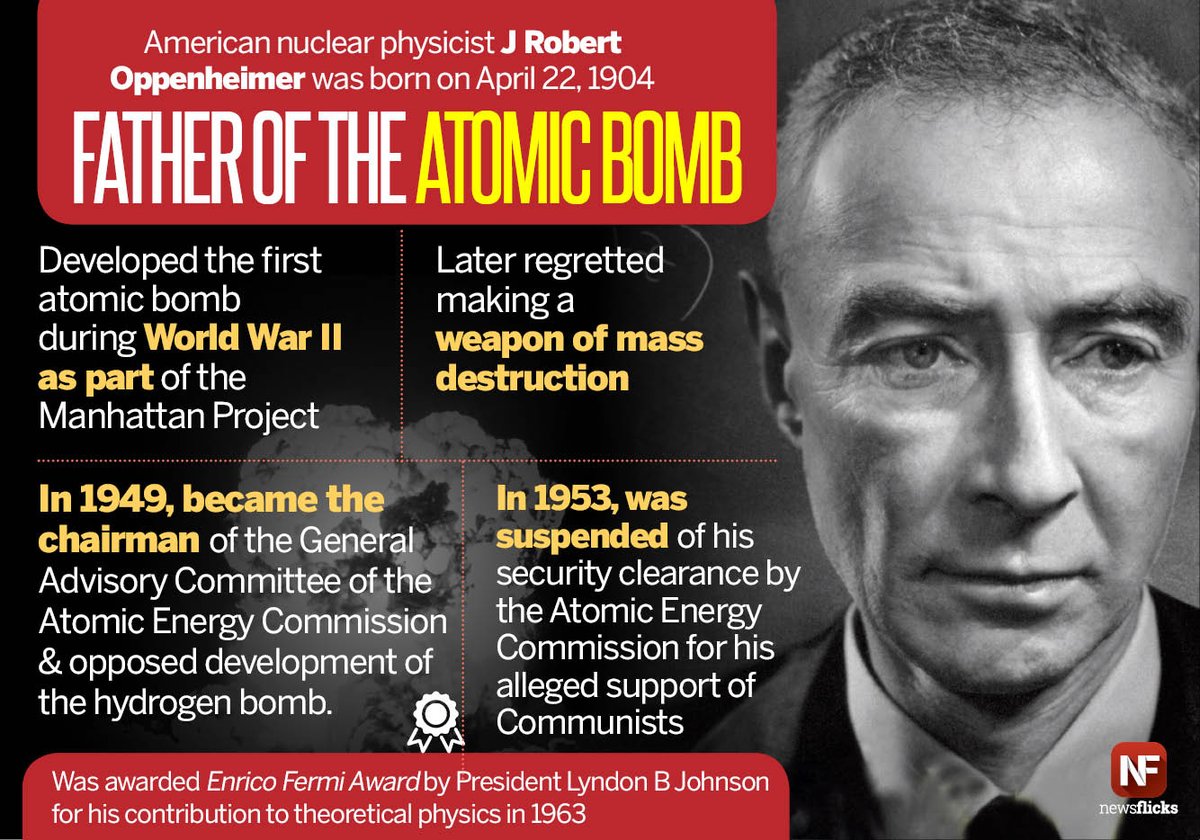

People often focus on the Trinity test. July 16, 1945. That's the big moment. But the real weight of being the father of the bomb came afterward, in the quiet rooms of the White House and the hearing rooms where his own government eventually turned on him. He wasn't just a scientist; he became a political symbol.

The Manhattan Project Was a Logistics Nightmare

Imagine trying to build a city from scratch with no Google Maps and a bunch of scientists who weren't allowed to tell their wives what they were doing. General Leslie Groves was the muscle, but Oppenheimer was the brain. They were the ultimate "odd couple." Groves was a career military man who built the Pentagon. Oppenheimer was a leftist intellectual who quoted poetry.

🔗 Read more: Why the Star Trek Flip Phone Still Defines How We Think About Gadgets

It shouldn't have worked.

But it did because Oppenheimer had this weird, magnetic charisma. He could speak to chemists, metallurgists, and theoretical physicists in their own languages. He understood the $2 billion scale of the project (that’s nearly $30 billion today, adjusting for inflation).

- He managed over 6,000 people at Los Alamos alone.

- He coordinated with sites in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington.

- He did all this while under constant FBI surveillance.

The technical hurdles were insane. They didn't even know if they had enough plutonium. They had to invent "implosion" technology because the "gun-type" method used for the Hiroshima bomb wouldn't work with the plutonium they were breeding. It was a race against a Nazi program that, as it turned out, wasn't even close to succeeding.

The "I Am Become Death" Myth

We’ve all heard the quote. "Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds." It’s from the Bhagavad Gita. Oppenheimer claimed he thought of it during the Trinity explosion.

Did he really?

Maybe. Or maybe he polished that story later to give the horror of the moment a sense of divine inevitability. His brother, Frank Oppenheimer, remembered it differently. He said Robert just looked at the mushroom cloud and said, "It worked."

💡 You might also like: Meta Quest 3 Bundle: What Most People Get Wrong

Simple. Chilling.

The father of the bomb title became a cage for him. After the war, he tried to use his influence to stop the development of the Hydrogen bomb—the "Super." He failed. Edward Teller, a man who would eventually testify against Oppenheimer, pushed for it. Oppenheimer saw the writing on the wall: we were entering an arms race that had no logical finish line.

The Security Clearance Trial and the Fall from Grace

In 1954, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance. It was a total hatchet job. They brought up his past associations with Communist Party members. They brought up his late-night visits to old friends. They essentially humiliated the man who had delivered the weapon that ended the war.

He was no longer the golden boy of American science.

He spent his final years at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He was still the father of the bomb, but he was a man out of time. He watched as the world built thousands of warheads, each many times more powerful than the "Gadget" he detonated in 1945. He never expressed "regret" in the way people wanted him to. He didn't say he was sorry for building the bomb. He said he was sorry that the world hadn't learned how to manage the peace.

There’s a nuance there that people miss. He believed the technology was inevitable. If he didn't build it, someone else would. His "sin," in his own eyes, was the belief that he could control the political outcome once the genie was out of the bottle.

📖 Related: Is Duo Dead? The Truth About Google’s Messy App Mergers

Practical Lessons from the Life of Oppenheimer

If you're looking at the father of the bomb and wondering what it means for us today, look at the way he handled multidisciplinary teams. That's the real "business" takeaway.

- Contextual Leadership: Oppenheimer didn't just manage; he translated. He made sure the guy working on the trigger understood why the guy working on the casing was behind schedule. In modern tech, we call this breaking down silos.

- The Ethics of Innovation: Never assume the "public" or "government" will use your tech the way you intended. If you build a tool, you are responsible for its existence, but you rarely control its application.

- Intellectual Breadth: He wasn't just a physicist. He read French literature. He studied Eastern philosophy. This "broad-spectrum" thinking allowed him to see the big picture when others were stuck in the math.

Navigating the Legacy

What do we do with the ghost of J. Robert Oppenheimer?

First, visit the Los Alamos National Laboratory website or their museum if you're ever in New Mexico. It’s an eerie place. You can still see the landscape that inspired him.

Second, read "American Prometheus" by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. It’s the definitive biography. It’s long, it’s dense, but it’s the only way to get past the 2D version of the man.

Third, pay attention to the current debates on AI regulation. The parallels are staggering. The creators of modern Large Language Models are having their own "Oppenheimer moments" right now, testifying before Congress and wondering if they’ve sparked a fire they can't put out.

The story of the father of the bomb isn't over. It’s just getting started. We are still living in the world he built—a world where peace is maintained by the threat of total annihilation. It’s a fragile balance. Understanding the man who tipped the scales is the first step in making sure we don't let them break entirely.

Check out the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and their "Doomsday Clock." It was founded by Manhattan Project scientists, including Oppenheimer, to track how close we are to the edge. Right now, in 2026, the clock is closer to midnight than it has ever been. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a legacy.

Next Steps for Deep Exploration

- Primary Source Research: Go to the Library of Congress Digital Collections and search for the "Oppenheimer Security Hearing transcripts." Reading the actual testimony reveals the sheer tension of the Red Scare era.

- Scientific Context: Research the difference between fission and fusion. Understanding why Oppenheimer opposed the "Super" (the H-bomb) requires a basic grasp of the jump in destructive power between the two technologies.

- Geopolitical Tracking: Follow the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) for real-time data on global nuclear stockpiles. It puts the work of the 1940s into a startling modern perspective.