He was a man of contradictions. Thin as a rail, fueled by little more than Chesterfields and gin, J. Robert Oppenheimer didn't just build a weapon; he changed how humanity views its own survival. People call him the father of the atomic bomb. It’s a heavy title. Most of us imagine a scientist in a lab coat, but "Oppie" was more like a high-strung conductor leading a chaotic, secret orchestra in the middle of the New Mexico desert.

The story usually goes like this: there was a race against the Nazis, the U.S. won, and Oppenheimer felt bad afterward. That's the SparkNotes version. But the reality? It’s way messier.

Honestly, the Manhattan Project wasn't even a sure thing for most of its run. It was a massive, multi-billion-dollar gamble during a time when the world was literally on fire. And Oppenheimer? He wasn't the obvious choice for the job. He had no Nobel Prize. He had zero experience managing people. He was a theoretical physicist who liked poetry and Sanskrit more than he liked military discipline. Yet, without him, the Gadget probably doesn't happen, at least not in 1945.

The Los Alamos Pressure Cooker

Building the atomic bomb wasn't just about the physics. It was about logistics. General Leslie Groves, the man who oversaw the Pentagon's construction, picked Oppenheimer because he saw a "pathological ambition" in him that others missed. Groves didn't care that Oppenheimer had left-wing political ties or that he’d never run anything bigger than a graduate seminar. He needed someone who could talk to the geniuses.

Los Alamos was a strange place. It was a makeshift town built on a mesa, surrounded by barbed wire. You had the smartest people on the planet living in drafty barracks with their families, forbidden from telling anyone where they were. It was high-stress. Imagine working 14-hour days on a project that might accidentally ignite the atmosphere—which, by the way, they actually crunched the numbers on to make sure it wouldn't happen. Edward Teller was there, already obsessing over a "Super" hydrogen bomb. Hans Bethe was heading the Theoretical Division. Richard Feynman was fixing typewriters and cracking safes just to prove the security sucked.

📖 Related: Brain Machine Interface: What Most People Get Wrong About Merging With Computers

Oppenheimer was the glue. He shed his weight, dropped down to about 100 pounds, and became a ghost-like figure wandering the halls. He had this uncanny ability to sit in a meeting, listen to five different experts argue, and then summarize their points better than they could themselves.

That "Destroyer of Worlds" Quote

We’ve all heard it. “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” He claimed he thought of that line from the Bhagavad Gita during the Trinity test on July 16, 1945. But did he? Some of his colleagues say he just looked relieved. Others remember him simply saying, "It worked." The "Destroyer of Worlds" bit came later, in a 1965 NBC interview. It was part of his self-mythologizing. Oppenheimer was deeply aware of his place in history, and he spent the rest of his life trying to frame the narrative of his own guilt.

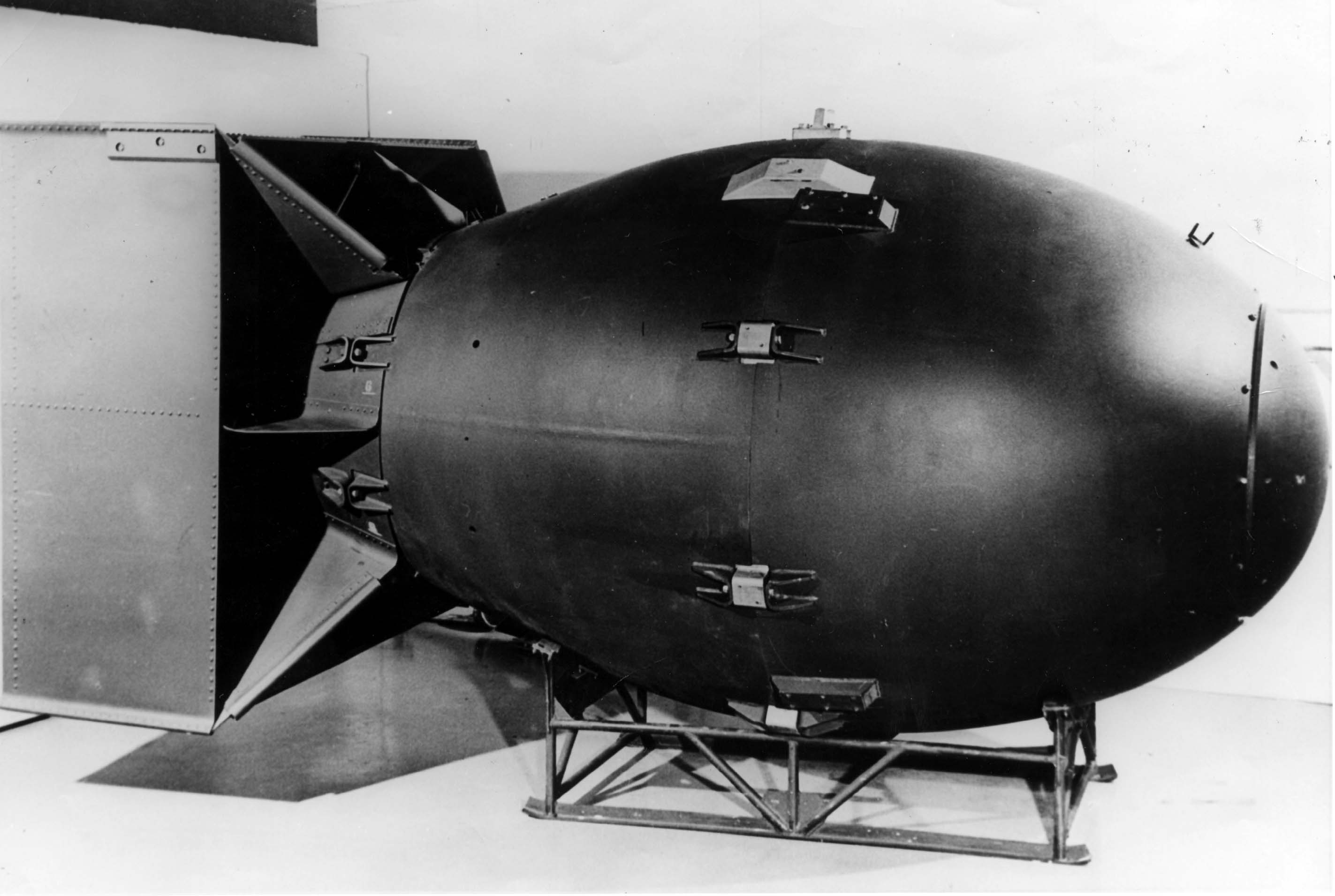

The Trinity test itself was terrifying. They hoisted the plutonium device, nicknamed the "Gadget," onto a 100-foot steel tower. When it went off, the flash was so bright that a blind girl miles away reportedly saw it. The sand turned to green glass. That glass is called Trinitite. You can still find bits of it today, though it's illegal to take from the site.

The Politics of the Fallout

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer became a household name. He was on the cover of Time. He was the ultimate insider. But he started pushing back. He didn't want the hydrogen bomb built. He called it a weapon of genocide.

👉 See also: Spectrum Jacksonville North Carolina: What You’re Actually Getting

This didn't sit well with the Cold War hawks.

By 1954, at the height of the Red Scare, Oppenheimer was hauled before a security hearing. It was a kangaroo court. Lewis Strauss, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, had a personal vendetta against him. They brought up his old flings with Communist Party members like Jean Tatlock. They questioned his loyalty. In the end, they stripped him of his security clearance.

It broke him.

He spent his final years in Princeton and a small beach shack in St. John. He didn't stop being a scientist, but he was no longer the "American Prometheus." He was a man who had been used by his country and then discarded once he became a "problematic" conscience.

✨ Don't miss: Dokumen pub: What Most People Get Wrong About This Site

Why We Still Obsess Over Him

Why do we care so much now? Partly because we’re back in an era of existential tech threats. Whether it’s AI or the next pandemic, we look at Oppenheimer as the original "oops, we built something we can't control" guy.

There's also the nuance of the decision to drop the bomb. It’s easy to judge from 2026. But in 1945, the U.S. was looking at a potential million casualties from a land invasion of Japan. The firebombing of Tokyo had already killed more people than the Hiroshima blast. To the leaders at the time, the atomic bomb was just a bigger hammer. Oppenheimer knew that, but he also knew that the world had fundamentally shifted.

The Real Legacy

Oppenheimer didn't invent the bomb alone. He was the catalyst. He was a man who understood that science isn't done in a vacuum. It has consequences. He once said, "The physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose."

He wasn't a saint. He could be cruel, arrogant, and incredibly naive. But he was honest about the tragedy of progress.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to actually understand the man behind the myth, don't just watch the movies. Dive into the primary sources.

- Read the transcripts: The 1954 security hearing transcripts are public. They read like a psychological thriller. You see exactly how the government turned on its own hero.

- Visit the Bradbury Science Museum: If you're ever in Los Alamos, this place has the best technical breakdowns of what they actually did during the Manhattan Project.

- Look into the "Quiet" Years: Study his time at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He mentored some of the greatest minds of the 20th century, proving his legacy wasn't just about destruction.

- Understand the "Szilard Petition": Look up Leo Szilard. He was the guy who actually conceived the nuclear chain reaction but later tried to stop the bomb's use. His conflict with Oppenheimer is a fascinating look at scientific ethics.

- Check out the "American Prometheus" biography: It’s the definitive text. It took 25 years to write for a reason.

The most important thing to remember about J. Robert Oppenheimer is that he never apologized for building the bomb. He only regretted that we didn't manage it better afterward. That’s a distinction worth thinking about.