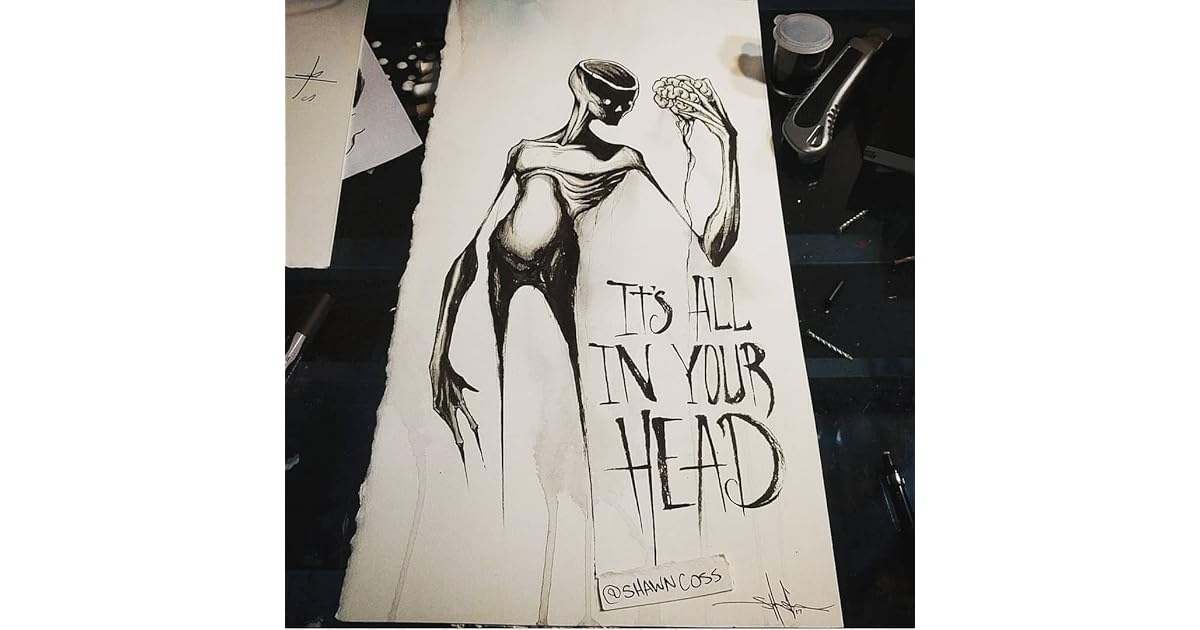

You've probably heard the phrase before. Usually, it's whispered by a doctor who can't find a tumor or shouted during a heated argument with a partner who thinks you’re exaggerating your back pain. It is dismissive. It is frustrating. But for Dr. Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, it’s a scientific reality that we’ve been looking at all wrong. When she wrote the It's All in Your Head book, she wasn't trying to gaslight patients. She was trying to prove that the mind can create physical illness just as "real" as a broken leg.

Medicine is weird. We like things we can see on an MRI. If a scan shows a slipped disc, we're happy; if it shows nothing but the patient can't walk, we panic. We call it "psychosomatic," a word that has become a dirty insult in modern healthcare. O’Sullivan spent years treating people who were blind, paralyzed, or suffering from seizures, yet had absolutely nothing structurally wrong with their bodies. This book is her attempt to bridge that massive, awkward gap between neurology and psychology.

The Physical Reality of Imaginary Things

It’s not "fake." That is the first thing you have to understand about the It's All in Your Head book and the cases O'Sullivan presents. She introduces us to people like Pauline, who spent her life cycling through various mysterious ailments, from joint pain to full-body infections. Pauline wasn't a "malingerer." She wasn't lying for attention. Her brain was simply translating emotional distress into physical symptoms because it had no other way to process the trauma.

Our brains are essentially the world's most complex chemical factories. They control every heartbeat, every breath, and every muscle twitch. When that system glitches due to stress or repressed emotion, the output isn't just "sadness." Sometimes the output is a seizure that looks exactly like epilepsy but doesn't show up on an EEG. O'Sullivan argues that these "dissociative seizures" are a biological defense mechanism.

Think about blushing. You get embarrassed, and your face turns red. You didn't tell your blood vessels to dilate. Your mind did that. Now, scale that up. If a simple emotion like embarrassment can change your skin color, why is it so hard to believe that deep-seated trauma could paralyze an arm?

👉 See also: What Does DM Mean in a Cough Syrup: The Truth About Dextromethorphan

Why We Hate the Term Psychosomatic

Honestly, the stigma is the biggest hurdle. Most people would rather be told they have a rare, incurable neurological disease than be told their symptoms are psychosomatic. Why? Because "psychosomatic" sounds like "you're crazy" or "you're making it up." In the It's All in Your Head book, O'Sullivan pushes back against this cultural bias. She points out that by refusing to accept the mind-body connection, patients often subject themselves to unnecessary, invasive surgeries and toxic medications that do more harm than good.

Take the case of "Yvonne." She was a high-flying consultant who suddenly went blind. There was no damage to her optic nerves. Her eyes worked perfectly. Her brain simply stopped processing the visual data. In the medical world, this is often called Conversion Disorder. It’s a terrifying diagnosis because it suggests that your own mind is a stranger to you. It suggests you aren't in control.

The Mystery of the "Leaking" Body

One of the most striking parts of the narrative involves the sheer variety of symptoms. We aren't just talking about headaches or "feeling tired." We're talking about:

- Inability to swallow (Globus pharyngeus)

- Complete loss of limb function

- Chronic fatigue that mimics glandular fever

- Non-epileptic attacks that cause people to collapse for hours

O'Sullivan is careful. She doesn't say everything is in your head. That would be dangerous. Instead, she highlights the difficulty of the "diagnosis of exclusion." Doctors have to rule out every possible physical cause before they even dare suggest the mind is at play. But as she points out, this often leads to a "diagnostic chase" where the patient gets sicker and more obsessed with finding a physical "fix" that doesn't exist.

✨ Don't miss: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

The Cultural Contagion Factor

It gets even weirder when you look at mass psychogenic illness. The book touches on how these symptoms can spread through a community. You’ve probably heard of the "Le Roy twitching" case in New York or the various "fainting epidemics" in schools. This isn't just teenage drama. It's a localized biological response to shared stress. When one person's brain finds a physical outlet for stress, other brains in close proximity can "copy" that output. It's like a software virus for the human nervous system.

It’s scary to think our health is that volatile. We want to believe we are solid. We want to believe our bodies are machines that only break when a part wears out. But O'Sullivan shows us that we are more like a piece of software. You can have the best hardware in the world, but if the code is buggy, the screen stays black.

What Most People Get Wrong About This Book

People often pick up the It's All in Your Head book expecting a self-help guide. It isn't that. It won't give you a "five-step plan" to think away your migraines. If anything, it’s a humbling look at how little we actually know about the brain.

A common misconception is that O'Sullivan is "blaming the victim." She isn't. She’s actually advocating for these patients. In the current medical system, once a doctor realizes a condition is psychological, they often lose interest. They stop caring because it's no longer "their department." O'Sullivan argues that these patients are actually the ones who need the most care, because their suffering is profound and their path to recovery is much more complex than just taking a pill.

🔗 Read more: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

Moving Toward Real Healing

So, how do you actually fix a problem that is "all in your head"? It's not as simple as "cheering up." The recovery often involves Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), physical therapy to "re-train" the brain to move the body, and a lot of uncomfortable honesty about one's life.

It requires a total shift in how we view health. We have to stop separating the "head" from the "body" as if they are two different entities. They are the same system. If you are reading this because you are dealing with unexplained symptoms, the takeaway isn't that you are "crazy." The takeaway is that your brain is incredibly powerful—powerful enough to shut down your body to protect you from something it can't handle.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Mind-Body Health

- Audit Your Stress Response: Start a journal that tracks your physical symptoms alongside your emotional state. Don't look for a one-to-one correlation immediately; look for patterns over weeks.

- Challenge the Stigma: If a doctor suggests a symptom might be stress-related, don't immediately get defensive. Ask: "If this is a mind-body response, what are the proven neurological pathways for treating it?"

- Seek Multidisciplinary Care: If you have chronic, unexplained pain, don't just see a specialist for that body part. Look for clinics that integrate neurology, physical therapy, and psychology.

- Understand the "Secondary Gain": This is a tough one. Ask yourself if your illness is providing a "solution" to a problem you can't solve otherwise (like avoiding a job you hate or a relationship that's failing). This isn't about guilt; it's about insight.

- Validate Your Pain: Remember that a psychosomatic symptom is felt exactly the same way as an organic one. The pain is real. The paralysis is real. Acknowledging the source doesn't make the experience any less valid.

The It's All in Your Head book remains a vital piece of medical literature because it forces us to confront the "ghost in the machine." We are not just biological robots. We are a messy, swirling mix of memory, trauma, and biology. Sometimes, the body screams because the mouth can't speak. Understanding that isn't just good medicine—it's basic human empathy.