History has a funny way of flattening people into caricatures. If you mention Isoroku Yamamoto in a casual conversation, most folks immediately picture a cold, calculating mastermind who lived to destroy the American fleet. He’s the face of the "surprise attack." The villain of the Pacific. But if you actually dig into his letters, his gambling habits, and his desperate attempts to avoid the very war that made him famous, you find a man who was basically a walking contradiction.

Yamamoto was a Harvard man. Think about that for a second.

He didn't just study the United States from afar; he lived there. He hitchhiked across the country. He saw the oil fields in Texas and the massive, smoking chimneys of the Detroit auto plants. While the hotheaded nationalists back in Tokyo were beating their chests about Japanese spiritual superiority, Yamamoto was doing the math. He knew Japan couldn't out-produce a giant like America. He knew that in a long war, Japan would eventually just run out of stuff.

The Gambler Who Hated the Odds

It’s no secret that Isoroku Yamamoto was an obsessive gambler. He loved poker, bridge, and shogi. Legend has it he even offered to retire from the Navy to become a professional gambler in Monaco because he was that confident in his ability to read people.

This wasn't just a hobby. It defined how he approached the Navy.

When he looked at the geopolitical landscape of the late 1930s, he saw a losing hand. Japan was bogged down in China, resources were getting tight, and the U.S. was starting to squeeze the oil supply. The "hawks" in the Japanese Army wanted to double down. Yamamoto, the guy who spent his nights winning at cards, told them they were being idiots. He famously warned the Japanese government that if they forced him to fight the U.S., he would "run wild" for six months to a year, but after that? He had "utterly no confidence" in what would happen.

That’s not the talk of a warmonger. That’s a man who knows he’s about to lose his shirt at the table.

Why Pearl Harbor Wasn't His First Choice

People often think Pearl Harbor was Yamamoto’s "grand plan" because he loved the idea of a sneak attack. Honestly, it was the opposite. It was a desperate, last-ditch effort to buy time.

🔗 Read more: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

He hated the idea of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. He actually received so many death threats from Japanese extremists for being "pro-Western" that the Navy had to hide him at sea by appointing him Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet. Talk about a weird promotion—"We're making you the boss so the neighbors don't kill you."

Once the decision for war was made by the civilian and army leadership, Yamamoto felt he had one move left: the "checkmate" on day one.

His logic was simple. If you can’t win a marathon, you have to knock the other guy out in the first ten seconds. He spent months obsessing over the logistics of shallow-water torpedoes. He knew the risks. He knew that if the American carriers weren't there, the plan would fail. And as we now know, the carriers weren't there.

The gamble failed.

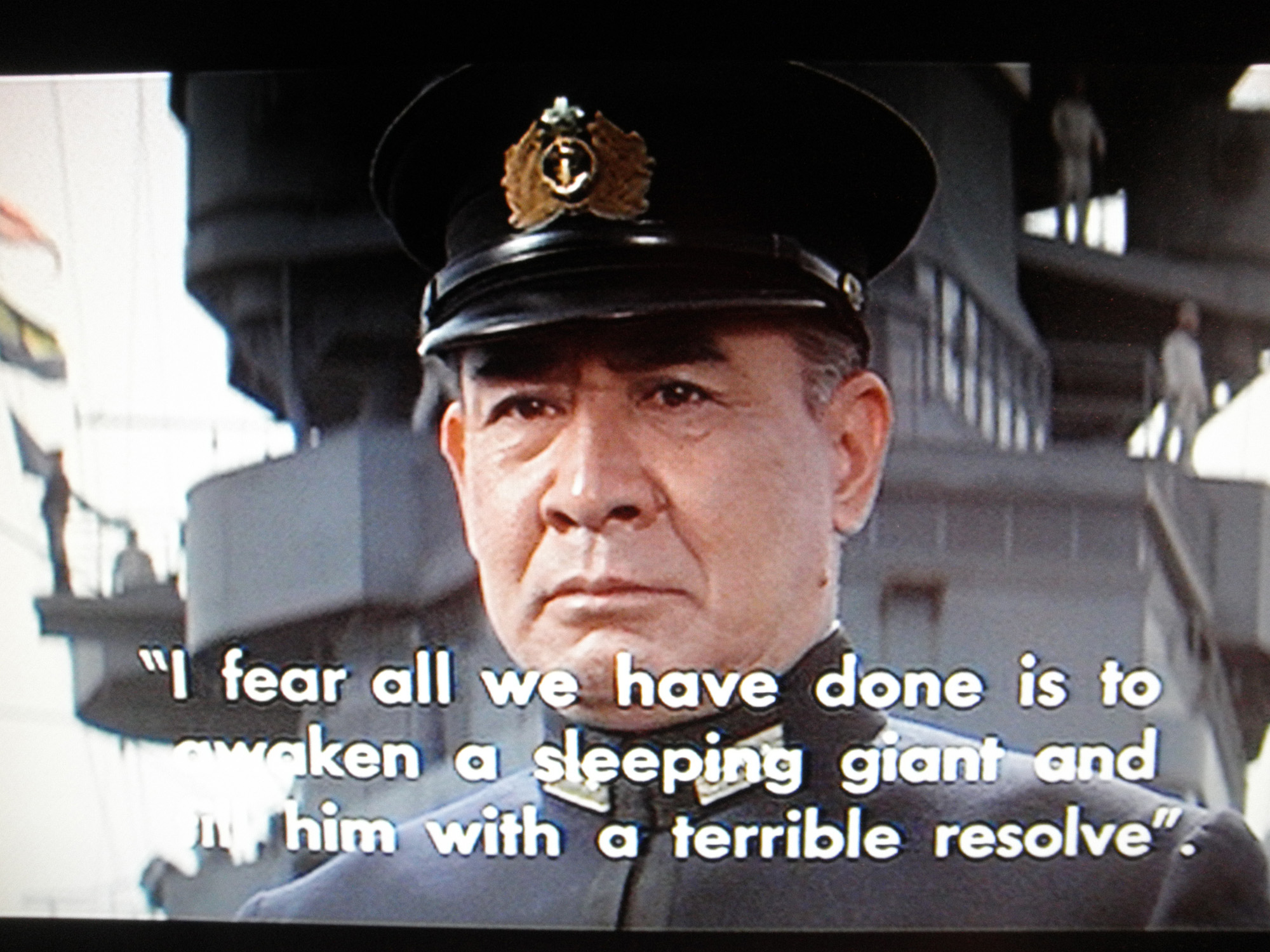

The Myth of the "Sleeping Giant" Quote

You’ve probably heard the famous line: "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve."

It’s a great quote. It’s dramatic. It’s perfect for a movie trailer.

It’s also almost certainly fake.

💡 You might also like: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

There is zero evidence in Yamamoto’s actual diaries or official records that he said this immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack. It first showed up in the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora! and then again in the 2001 Pearl Harbor movie. While the sentiment definitely matches his private anxieties, the man himself was much more reserved in his actual writing.

What he did write was much bleaker. He wrote about his deep sense of shame and the fact that he expected to die in the cockpit of a plane or on the deck of a ship. He wasn't looking for glory; he was looking for an exit strategy that didn't exist.

The Midway Disaster and the End of the Streak

If Pearl Harbor was his greatest gamble, the Battle of Midway was his greatest blunder.

Yamamoto tried to be too clever. He created a plan so complex, with so many moving parts and diversions (like the Aleutian Islands campaign), that it became brittle. He assumed the Americans were demoralized. He didn't know—or didn't want to believe—that U.S. codebreakers like Joseph Rochefort were reading his mail.

The Americans knew exactly where he was going.

When the Japanese carriers started burning at Midway, the tide of the war didn't just turn; it crashed. Yamamoto spent the rest of the war in a reactive state, trying to hold onto the Solomon Islands while the American industrial machine—the one he had feared back in Detroit—began to pour out ships and planes at a rate Japan couldn't even imagine.

Operation Vengeance: A Very Specific Hit

The way Isoroku Yamamoto died is probably the most telling part of his entire story.

📖 Related: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

By 1934, he was a celebrity. By 1943, he was a target. The U.S. intercepted a message detailing his inspection tour of the Solomon Islands. The schedule was precise—down to the minute.

U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz had a tough choice. Do you kill the enemy’s best commander and risk him being replaced by someone better? Or do you take the win? They checked with intelligence, and the consensus was that Yamamoto was the "heart" of the Japanese Navy.

On April 18, 1943, P-38 Lightnings intercepted Yamamoto’s transport plane. They shot it down over the jungle of Bougainville.

When Japanese search parties found him, he was still sitting upright in his seat, his hand on his sword. It was a poetic, almost cinematic end for a man who spent his life trying to balance his loyalty to his country with his knowledge that his country was making a fatal mistake.

Real-World Lessons from a Complicated Legacy

So, why does any of this matter today? Isoroku Yamamoto isn't just a figure from a dusty textbook. His life offers some pretty sharp insights into leadership and strategy that still hold up.

- Don't ignore the logistics. Yamamoto knew the U.S. had more "stuff." His bosses ignored him. In any project, the person who understands the supply chain usually wins.

- Know your opponent. Because he lived in the U.S., he understood the American psyche better than anyone in Tokyo. He knew they wouldn't quit after a surprise attack; he knew they'd get mad.

- The danger of "The Plan." At Midway, Yamamoto fell in love with his own complex plan and failed to account for the enemy having a vote. Flexibility is usually better than complexity.

If you want to understand the Pacific War, you have to stop seeing Yamamoto as a villain and start seeing him as a man caught in a trap of his own making. He was an expert strategist who was forced to play a game he knew he couldn't win.

How to Explore This Further

If you’re looking to get past the Hollywood version of this story, there are a few things you can do to see the real Isoroku Yamamoto.

- Read his actual letters. Look for translations of his correspondence with his mistress, Kawai Chiyoko. They reveal a much more human, insecure, and thoughtful version of the Admiral than any official biography.

- Study the Battle of Leyte Gulf. To see how the Japanese Navy fell apart after his death, compare the strategic coherence of his early campaigns to the chaos that followed in 1944.

- Visit the Nimitz Museum. If you're ever in Fredericksburg, Texas, the National Museum of the Pacific War has an incredible collection that puts his decisions into the context of the global resource struggle.

Understanding Yamamoto requires acknowledging that a person can be both a brilliant leader and a tragic failure at the same time. He didn't want the war, but he fought it with everything he had, knowing full well how it would end.

Actionable Insight: When evaluating a high-stakes situation—whether in history or modern business—always look for the "reluctant expert." The person who is warning you about the risks is often the one who understands the landscape best. Like Yamamoto, they might have the skills to execute a plan, but their hesitation is usually backed by data you can't afford to ignore.