You probably remember the cover. A girl with tan skin, dark hair, and a gaze that looks like she’s seen things most kids couldn’t imagine. Maybe there’s a dog beside her. Scott O'Dell’s 1960 novel is a staple of middle school existence, but when you go looking for island of the blue dolphins images, you realize something quickly. Most of what we see is a myth. Or at least, it's a very specific, stylized version of a much grimmer reality.

The book is based on the true story of Juana Maria. She was the "Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island." She spent 18 years alone on a windswept, desolate rock off the coast of California. When we search for visuals, we usually find soft, watercolor illustrations from the various book editions. They’re beautiful. They’re also kind of misleading.

Why the real San Nicolas Island looks nothing like the books

The real island is a brutal place. It isn't a tropical paradise with swaying palms. If you look at actual topographical island of the blue dolphins images—the ones from the U.S. Navy, which currently controls San Nicolas—the landscape is brown, scrubby, and dominated by sandstone. It's roughly 60 miles from the mainland. It’s windy. Like, "blow your tent away" windy.

- The sandstone cliffs are carved by salt spray.

- Vegetation is mostly low-lying sea heath and prickly pear.

- It’s a place of fog and harsh light, not just golden sunsets.

Scott O’Dell took some liberties. That’s fine; it’s fiction. But the images in our heads of a lush, verdant island don't match the reality of the Channel Islands. Juana Maria didn't live in a garden. She lived in a maritime desert.

The archaeology of the whale bone house

One of the most iconic island of the blue dolphins images is Karana’s house made of whale ribs. You’ve seen the drawings. They look like a ribcage arched over a small dwelling. This wasn't just a cool idea O'Dell had. It was a real thing.

Archaeologists like Steven Schwartz, who worked on the island for decades, actually found evidence of these structures. In the 1800s, there were sketches made of the abandoned Nicoleño village. These early island of the blue dolphins images—or rather, the historical sketches they inspired—show that the Nicoleño people used what they had. When you have no tall trees, you use the bones of the sea.

Think about that.

Imagine hauling a massive blue whale rib up a cliffside. It's heavy. It's greasy. It’s a testament to incredible strength. Juana Maria wasn't just surviving; she was engineering.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The cormorant dress: Fact vs. Illustrator's imagination

If you look at the 50th-anniversary edition or the various paperback covers, the "green cormorant dress" is always a highlight. It’s usually depicted as a sleek, shimmering garment. In some island of the blue dolphins images, it looks like something you’d see on a runway.

The reality was much more practical and, frankly, a bit more macabre.

The dress was made from the skins of cormorants. These are dark, oily sea birds. To make a dress out of them, you have to skin dozens of birds, scrape the fat off, and sew them together using sinew. It wouldn't have been a breezy summer dress. It would have been heavy, waterproof, and probably smelled strongly of fish and old oil.

- The "Green" Hue: Cormorant feathers have an iridescent sheen. In the right light, they flash emerald and violet.

- The Construction: It was a feat of needlework. Juana Maria used needles made of bone and thread made of seal sinew.

- The Fate of the Dress: When she was finally "rescued" in 1853 and brought to Santa Barbara, the dress was a sensation. People were obsessed with it. Sadly, it was reportedly sent to the Vatican and was later lost, possibly in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. We don't have a photo. We only have the descriptions of those who saw it.

The problem with Hollywood's version of Karana

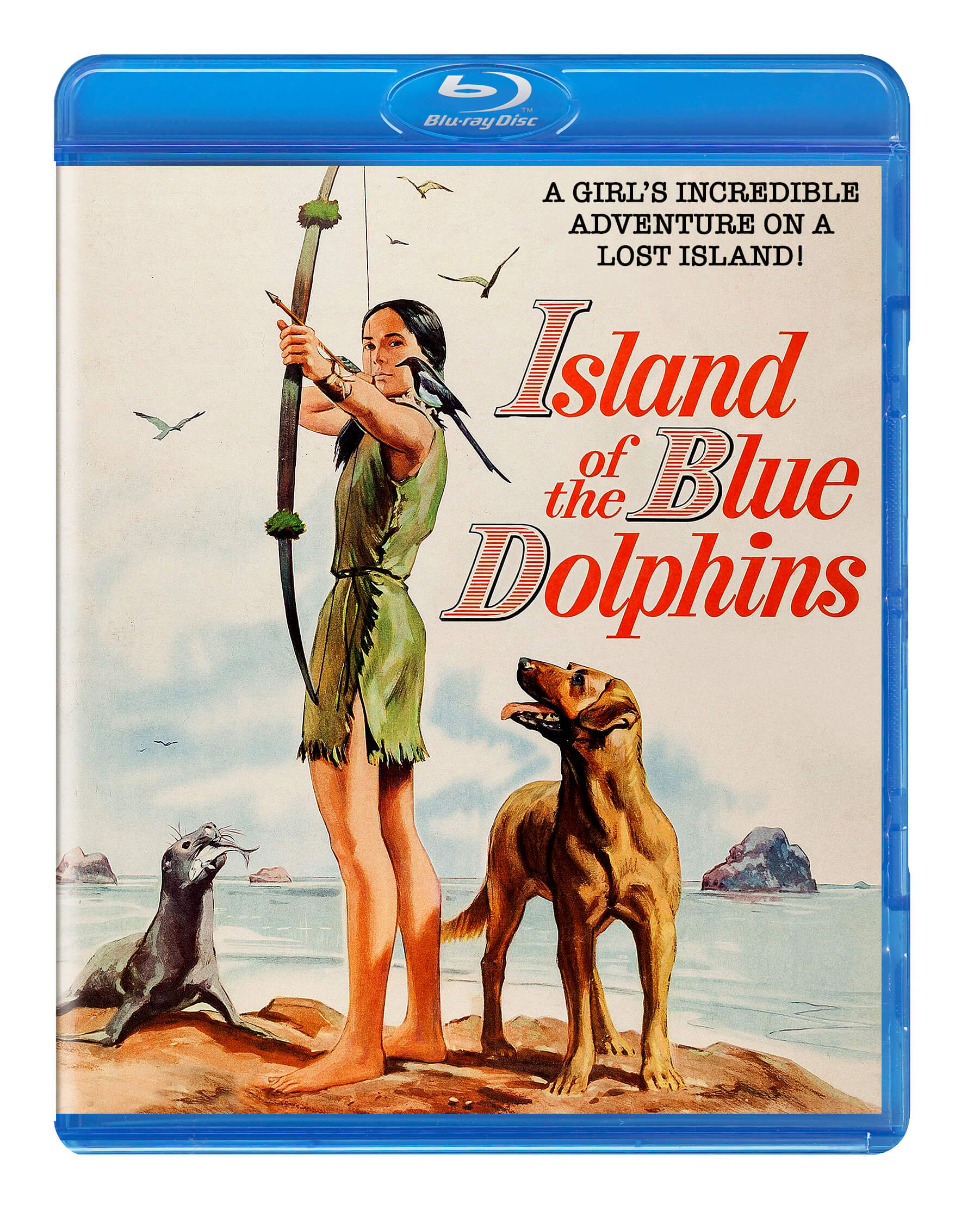

In 1964, a movie came out. If you search for island of the blue dolphins images from the film, you’ll see Celia Kaye playing Karana. She’s great, but let’s be honest—she looks like a 1960s starlet who just stepped out of a salon. Her hair is perfectly coiffed. Her makeup is subtle but definitely there.

It’s the classic Hollywood "survival" look where the protagonist never actually looks dirty.

This has skewed our internal database of what the story looks like. The real Juana Maria was likely in her 40s or 50s when she was found. Her skin was weathered. Her teeth were worn down from years of using them as tools to soften hides and cordage. She wasn't a teenager. She was a middle-aged woman who had mastered an environment that would kill most of us in a weekend.

Honestly, the most accurate island of the blue dolphins images are the ones that focus on the tools. The water baskets lined with asphaltum (natural tar). The harpoons tipped with bone. The small soapstone carvings of whales and dogs found in caches on the island. These are the "photos" of her life that remain.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

The cave that wasn't there (but then was)

For years, people looked for "Karana’s Cave." Scholars were skeptical. They thought O'Dell made it up for dramatic effect. Then, in 2012, a team of archaeologists found a cave that had been buried under sand for over a century. It matched the descriptions.

This discovery changed the way we look at island of the blue dolphins images from a historical perspective. It wasn't just a story. There was a physical space where a woman sat, listened to the wind, and waited.

Inside the cave, they found artifacts. They found a cache of items tucked into a redwood box—a box that likely drifted to the island from a shipwreck or was traded from the north. This is where the nuance comes in. The island wasn't a vacuum. Even in her isolation, Juana Maria was using the debris of the globalized world to stay alive.

The dogs of San Nicolas Island

We can't talk about island of the blue dolphins images without talking about Rontu. In the book, he’s a leader of the wild dogs, a remnant of the Aleut hunters' stay.

Historically, there were dogs on the island. They weren't just "wild dogs." They were a specific breed of indigenous dog, likely similar to the techichi or other small, sturdy dogs used by coastal tribes. They were companions, but they were also workers.

When you see modern illustrations of Rontu, he usually looks like a German Shepherd or a husky. That’s probably wrong. He would have been smaller, with a thick coat suited for the damp, salty air. The relationship between the woman and the dog wasn't just a "girl and her pet" trope. It was a partnership born of mutual loneliness.

How to find authentic visual references today

If you're a teacher, a student, or just a fan of the book looking for the real deal, don't just search "Karana." You have to dig a little deeper into the archives.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

First, look for the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library. They hold some of the most important documents regarding Juana Maria. While there are no photographs of her alive—photography was in its infancy in 1853 and she died just seven weeks after reaching the mainland—there are sketches made by people who spoke to those who knew her.

Second, check out the National Park Service photo galleries for the Channel Islands. Look specifically at San Nicolas. Look at the "Elephant Seal Beach." Look at the "Thousand Springs" area. These give you the texture of her world. The grey water. The white foam. The sharp rocks.

Third, look at the Chumash and Nicoleño basketry collections at the Smithsonian or the Autry Museum. The images of these baskets tell you more about Karana than any book cover ever could. They show the intricate patterns and the sheer skill required to make a vessel that could hold water using only natural materials.

Acknowledging the tragedy

We like the "adventure" of the story. But when we look at island of the blue dolphins images, we have to remember they represent a survivor of a genocide. The Nicoleño people were decimated by Russian and Aleut fur traders. The "rescue" was actually the removal of the last person from her ancestral home.

She wasn't "lost." The world she knew was destroyed.

When she got to Santa Barbara, she couldn't communicate with anyone. Her language was unique to her island. Think about that for a second. She’s surrounded by people for the first time in two decades, and she is still, effectively, alone. She died of dysentery shortly after her arrival because her immune system wasn't prepared for mainland diseases. It’s a heavy ending that the book softens slightly.

Actionable steps for exploring the visual history

If you want to move beyond the generic search results and really understand the visual world of Karana, here is what you should actually do:

- Visit the Channel Islands National Park website. Browse their "history and culture" section for San Nicolas Island. They have high-resolution photos of the actual terrain.

- Search for "Nicoleño artifacts" on the Smithsonian Institution's website. This gives you a look at the actual needles, hooks, and carvings found on the island.

- Look up the work of illustrator Ted Lewin. His work for the book is often cited as some of the most evocative, even if it leans into the "beautiful" side of the narrative.

- Examine the 1850s sketches of Santa Barbara. This shows the world Juana Maria stepped into. It was a dusty, colonial outpost, a far cry from the "civilization" she might have expected.

The images we associate with the story are often a filter. We see the bravery, but we miss the grit. We see the "Blue Dolphins," but we miss the cold, grey reality of the Pacific. By looking at the real island of the blue dolphins images—the ones from archaeology and history—we actually respect the woman behind the myth a lot more. She wasn't a character in a fable. She was a person who survived the impossible.

The real San Nicolas Island is still there, mostly empty, still windy, still holding the secrets of the woman who refused to be forgotten.