Mars is a freezing, radiation-blasted desert. It’s dry. If you stood on the Martian surface today and poured out a glass of water, it wouldn't just sit there. Because the atmospheric pressure is so incredibly low—about 1% of Earth’s—the water would basically boil and freeze at the same time. This weird process is called sublimation. So, when people ask about water on Mars, they aren't usually talking about lakes you can swim in or rushing rivers. They’re talking about a multi-billion-year-old mystery that we’re only just starting to solve.

The Ghost of a Blue Planet

Look at the photos from the Curiosity or Perseverance rovers. You’ll see it immediately. There are dried-up riverbeds, ancient deltas, and smoothed-out pebbles that look exactly like the ones you’d find in a creek in Montana. Scientists like Bethany Ehlmann at Caltech have spent years looking at these mineral deposits. They’ve found clays and sulfates that only form when rock sits in liquid water for a long, long time.

Billions of years ago, Mars had a thick atmosphere. It was warm. It had a "Northern Ocean" that might have covered a third of the planet. But then, the core cooled down. The global magnetic field failed. Without that shield, the solar wind—a stream of charged particles from the sun—stripped the atmosphere away. The water didn't just vanish into thin air; it mostly retreated or froze.

Where is it hiding now?

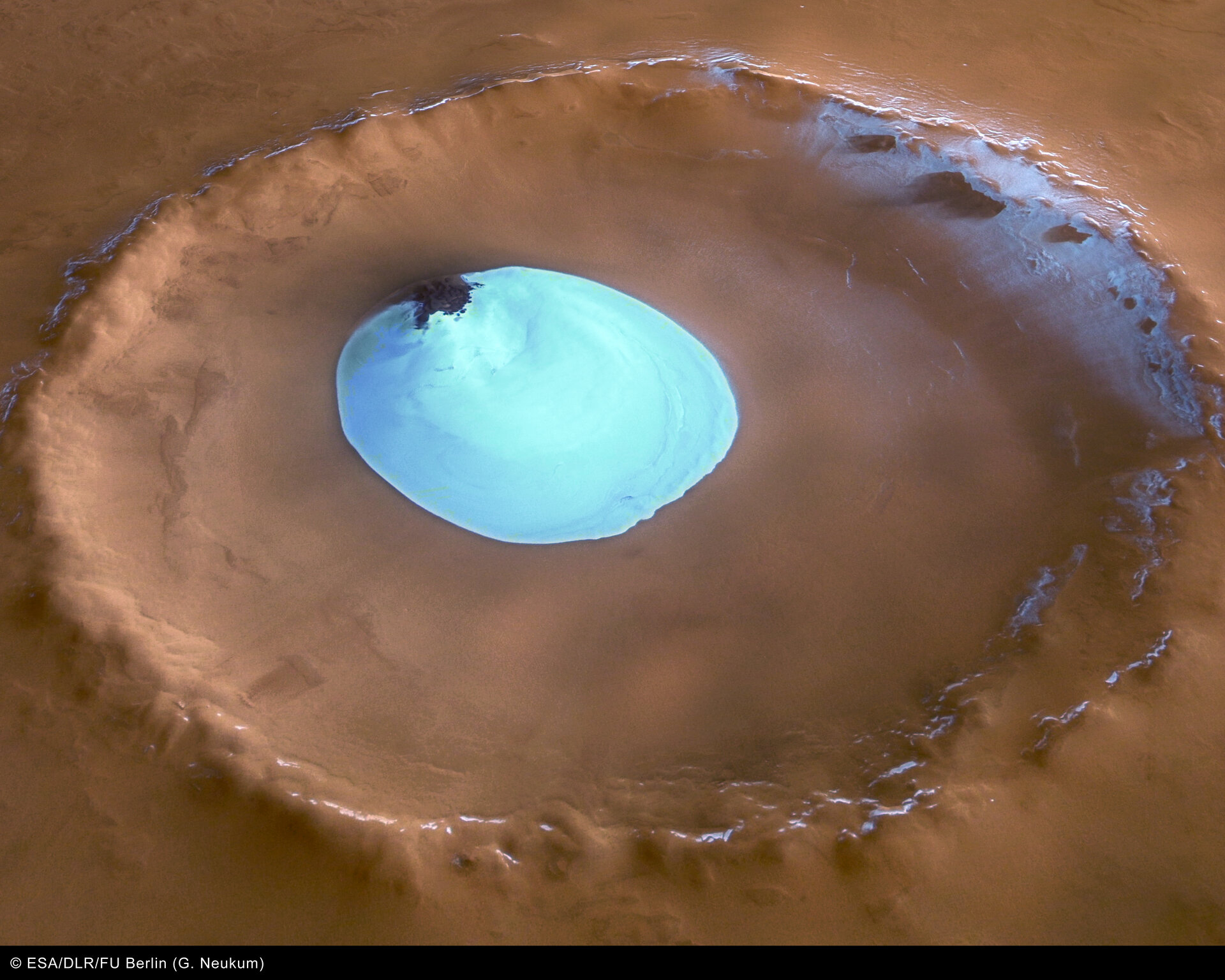

Most of the water on Mars is locked up in the polar ice caps. If you melted the south polar ice cap alone, the entire planet would be submerged under 36 feet of water. That’s a lot of ice. But it’s not just pure water; it’s a "dirty" mix of water ice and frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice).

Then you have the subsurface. This is where things get really interesting for NASA and SpaceX. We have strong evidence of massive ice sheets buried just a few meters under the dust in the mid-latitude regions. Using the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), researchers found "lobate debris aprons," which are basically glaciers covered in a thick layer of dirt that protects them from evaporating into space.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With Gator: The Rise and Fall of the Internet's Most Hated Software

The Great Liquid Debate: RSLs and Brine

For a few years, everyone was obsessed with Recurring Slope Lineae (RSL). These are dark streaks that appear to "flow" down Martian craters during the warm seasons. In 2015, NASA made a huge announcement suggesting these were caused by flowing liquid brine—very salty water that stays liquid at lower temperatures.

But science is messy.

Later studies, including work using the HiRISE camera, suggested these streaks might just be dry grains of sand cascading down slopes. It was a bit of a letdown for the "liquid water" hunters. However, we haven't ruled out the possibility of deep groundwater. Some radar data from the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter hinted at a massive liquid lake buried 1.5 kilometers under the ice at the south pole. Other scientists are skeptical, arguing the "reflection" seen in the radar could just be conductive clays or volcanic rock. Honestly, we won't know for sure until we put a drill on the ground.

📖 Related: How to Download Images From Chrome: What Most People Get Wrong

Is the water actually drinkable?

If you're an astronaut landing in Jezero Crater, you can't just shove a straw into the ground. Martian water is notoriously high in perchlorates. These are salts that are toxic to humans and can mess with your thyroid. To use water on Mars, we’d need to mine the ice, melt it, and then put it through an intensive desalination and purification process.

It's not just for drinking, though. Water is rocket fuel. By splitting $H_2O$ into Hydrogen and Oxygen, you get the propellant needed to get back home. This is the "In-Situ Resource Utilization" (ISRU) dream.

The Search for Martian Life

Why do we care so much about a few ice cubes in the dirt? Because of the "Follow the Water" rule. Everywhere we find liquid water on Earth, we find life. Even in the boiling vents of the ocean floor or the frozen lakes of Antarctica. If Mars had liquid water for a billion years, it had a window of habitability.

Whether life still exists in the damp pore spaces of deep underground rocks is the million-dollar question. We’ve seen methane spikes in the atmosphere, which could be biological, but they could also just be geological burps.

The Practical Reality for Future Missions

If you're following the progress of the Starship program or NASA’s Artemis goals, you know that finding accessible water is the "make or break" factor for a permanent base. We’re looking at the "Glacier Map" of Mars. Sites like Arcadia Planitia are top contenders because they seem to have vast, flat sheets of ice just beneath the surface.

The strategy is simple:

👉 See also: Why Black and White Wallpaper iPhone Aesthetics Are Making a Serious Comeback

- Map the ice: Use orbital radar to find the shallowest deposits.

- Sample the ice: Send robotic landers to drill a few meters down.

- Automate extraction: Build "Rodwell" systems (Rodriguez Wells) that circulate warm water to melt an underground bulb of ice and pump it to the surface.

This isn't science fiction anymore. It's a logistics problem.

What We Still Don't Know

We don't know the exact volume of the deep subsurface ice. We don't know if the "brine" sightings are actually liquid or just damp sand. And we certainly don't know if that water ever hosted a single microbe.

The story of water on Mars is the story of a planet that died, but left its lifeblood frozen in the veins of its crust. Every time a rover like Perseverance scrapes the surface, we’re looking for that one definitive sign that the planet isn't just a graveyard.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Martian Frontier

To stay updated on the latest findings regarding Martian water, follow these specific channels:

- Check the HiRISE Image Catalog: The University of Arizona regularly updates its high-resolution gallery of the Martian surface. Look for "seasonal changes" in craters.

- Monitor the Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment (MOXIE): While focused on air, the tech being developed for it directly relates to how we will eventually process Martian ice into resources.

- Follow the Planetary Science Journal: This is where the heavy-hitting peer-reviewed studies regarding radar reflections and mineralogy are published.

- Watch the Artemis Accords: These international agreements will dictate how different countries "own" or use the water ice found on planetary bodies.