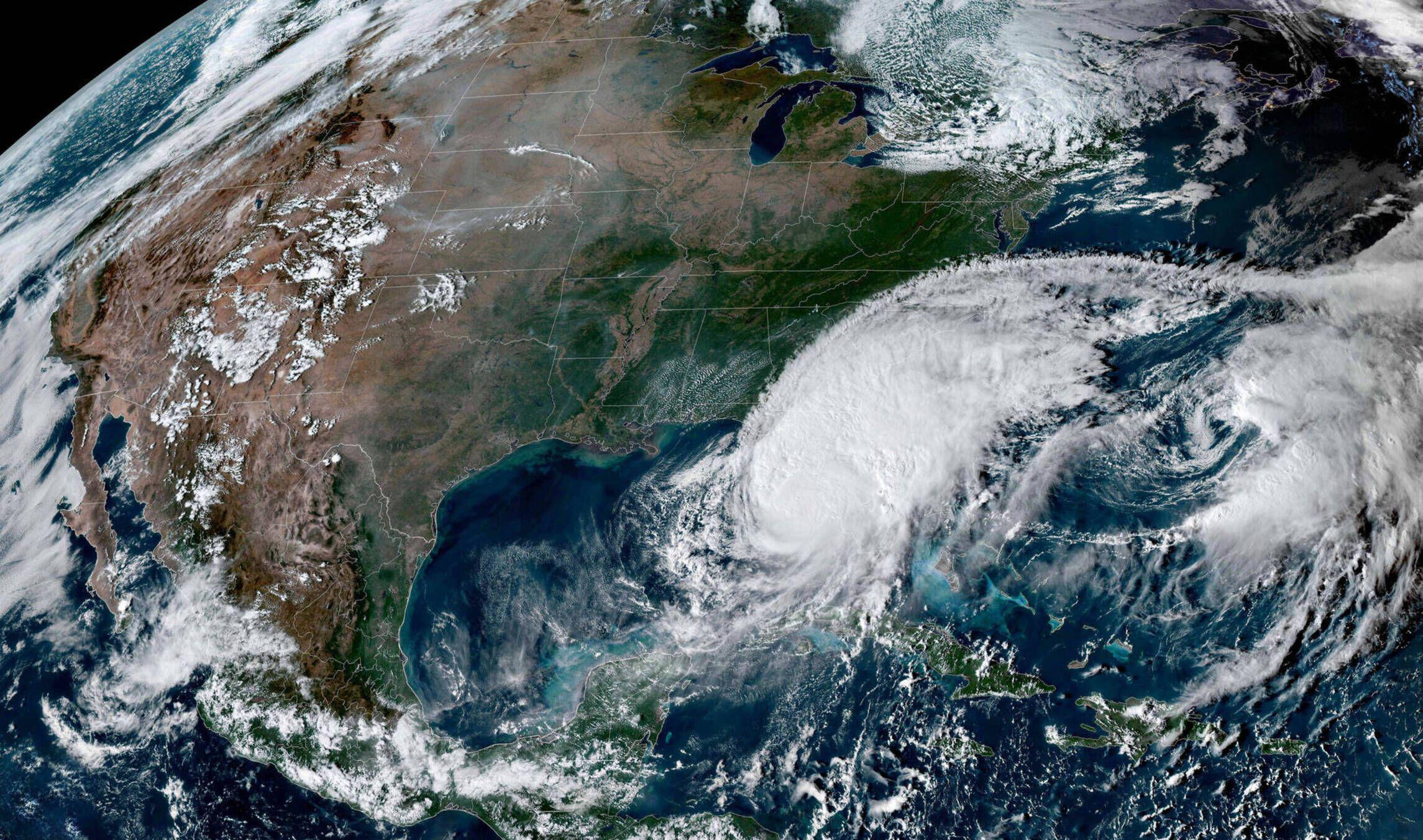

Milton was a monster. There is really no other way to put it. After watching a Category 5 storm explode in the Gulf and tear across Florida, everyone is looking at the satellite feed with a knot in their stomach. You've probably seen the headlines or the frantic TikTok weather maps showing colorful blobs headed for the coast. It feels like the atmosphere is stuck on repeat. But honestly, when we talk about a new hurricane forming after Milton, we have to separate the actual meteorological data from the social media hype. The ocean is still warm, and the season isn't technically over, but the setup in the Atlantic has shifted significantly since Milton made landfall near Siesta Key.

People are exhausted. Between Helene’s catastrophic flooding in the Appalachians and Milton’s tornadic power, the collective anxiety is at an all-time high. It’s understandable to look at every tropical wave coming off the coast of Africa as a potential threat.

The Current State of the Atlantic: What’s Brewing?

Right now, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) is keeping a close eye on several areas of interest. One area that garnered attention recently was Nadine, which eventually moved into Central America. But what about the "next one"? Meteorologists like Denis Phillips and the team at the NHC are currently monitoring a broad area of low pressure in the southwestern Caribbean Sea.

This region is a classic "hot spot" for late-season development. Why? Because while the main Atlantic development region (MDR) starts to cool down or get shredded by wind shear, the Caribbean stays incredibly hot. We’re talking about sea surface temperatures that are still hovering around 29°C to 30°C. That is high-octane fuel for any low-pressure system that manages to find a pocket of calm air.

If a new hurricane forming after Milton does materialize, it will likely follow the path of least resistance. Late in the season, that often means a northward turn. However, there is a massive "if" involved here. For a storm to become the next Milton, it needs three things: warm water, low wind shear, and high moisture. Right now, the wind shear—which acts like a giant pair of scissors cutting the top off a developing storm—is starting to ramp up across the Gulf of Mexico. That’s actually great news for the U.S. coastline.

Why the "Post-Milton" Phase Feels Different

It's weirdly quiet in some spots and chaotic in others. After a major storm like Milton, the ocean often undergoes a process called "upwelling." The storm's massive winds churn the water, bringing colder layers from the deep up to the surface. This usually leaves a "cold wake" behind the hurricane. A new hurricane forming after Milton would have a hard time crossing that same path because the energy has been sucked out of the water.

👉 See also: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

Think of it like a forest fire. Once a fire burns through a patch of woods, there’s no fuel left for a second fire to start immediately in the same spot. The Gulf needs time to "recharge" its heat content.

However, the Caribbean is a different story. It wasn't cooled down by Milton.

The Names to Watch

If you’re tracking the 2024-2025 cycle, the names are pre-set. After Milton came Nadine and Oscar. If another system gathers enough strength to reach 39 mph sustained winds, it gets the next name on the list: Patty.

Is Patty going to be the next big threat? Honestly, the models are split. The European model (ECMWF) and the American model (GFS) have been fighting back and forth. One day the GFS shows a major hurricane hitting Cuba; the next day, it shows nothing but a rainy mess in the open ocean. This is why you shouldn't trust a "spaghetti model" forecast that is more than seven days out. It’s basically weather fiction at that point.

Understanding the "Central American Gyre"

You might hear meteorologists talk about a "Gyre." It sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie, but it’s just a large, broad area of low pressure over Central America. This "gyre" is often the parent of late-season storms. It’s messy. It’s disorganized. But occasionally, a small spin within that big mess breaks off and becomes a tropical depression.

✨ Don't miss: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

This is exactly how many November storms start. They don't usually come from Africa as "Cape Verde" storms this late in the year. They are home-grown in the Caribbean.

The Role of Wind Shear and Cold Fronts

We are entering the time of year when cold fronts start dipping down from Canada. These fronts are the natural enemies of hurricanes. A strong cold front can act as a physical wall, pushing a new hurricane forming after Milton away from the United States and out into the Atlantic.

- Positive Scenario: A front pushes the storm East, away from land.

- Negative Scenario: A front stalls out and "pulls" the storm toward the coast, which is exactly what happened with some of the worst October storms in history, like Hurricane Sandy or Michael.

Real Data vs. Fear-Mongering

Let's talk about the "weather enthusiasts" on Facebook. You know the ones. They post a map with a giant red circle and the caption "FLORIDA IN THE CROSSHAIRS AGAIN??" It gets thousands of shares because people are scared.

But look at the actual NHC Tropical Weather Outlook. If the map is mostly white or has a yellow "X" with a 20% chance of development, take a deep breath. A 20% chance over seven days is not a reason to panic-buy plywood. Even a new hurricane forming after Milton wouldn't necessarily be a major storm. Many late-season systems struggle to maintain a core because the atmosphere is just too unstable.

What You Should Actually Be Doing Now

If you live in a coastal area, "hurricane fatigue" is real. You've spent weeks cleaning up branches, dealing with insurance adjusters, or maybe you're still waiting for power to be fully restored in some remote areas. The last thing you want to do is think about another "H" word.

🔗 Read more: Typhoon Tip and the Largest Hurricane on Record: Why Size Actually Matters

But the reality of living in the 2020s is that the season is longer.

- Check your supplies, but don't overbuy. You probably already have the water and canned goods left over from Milton. Check the expiration dates.

- Clear the drains. One of the biggest issues with a new hurricane forming after Milton isn't always the wind; it's the rain. After Milton, many drainage systems are clogged with debris and sand. A "minor" tropical storm could cause massive street flooding just because the water has nowhere to go.

- Secure your debris. If you still have a pile of Milton's wreckage on your curb, try to get it moved or at least weighed down. Even a 40 mph gust from a tropical wave can turn a piece of aluminum siding into a projectile.

- Follow the pros. Stick to the National Hurricane Center or your local meteorologists. Avoid the "doom-casters" who use thumbnail images of 500-foot waves.

The Caribbean is definitely "open for business" right now, but that doesn't mean a catastrophe is imminent. The atmosphere is complex. The transition into a La Niña pattern—which generally makes the Atlantic more active—is still ongoing, but the seasonal shift toward winter is our best defense.

We are seeing a trend where storms develop faster and stay stronger longer due to record-high ocean heat content. This isn't a theory; it's what we saw with Milton's record-breaking intensification. Because of this, the window for a new hurricane forming after Milton to become a problem is shorter. It could go from a "disturbance" to a "hurricane" in 36 hours.

Stay vigilant, but don't let the "what-ifs" ruin your week. The odds of a direct hit on the same location twice in one month are historically low, though not impossible. Most of the current activity is projected to stay well south of the U.S. mainland or drift harmlessly into the central Atlantic. Keep your weather radio handy, keep your gas tank at least half full, and keep an eye on the Caribbean low. Knowledge is the best way to kill the anxiety that these storms bring.

Immediate Steps for Coastal Residents

If a system does get named in the coming days, your first move shouldn't be the grocery store. It should be your yard. Loose items are the number one cause of broken windows in late-season storms. Check your "hurricane kit" and make sure your batteries aren't leaked. Most importantly, stay informed through official channels. The NHC updates their maps every six hours (2 AM, 8 AM, 2 PM, 8 PM). If those maps don't show a colored blob headed your way, you can go back to your normal life. The season officially ends November 30th, and while Mother Nature doesn't always look at the calendar, we are definitely in the home stretch of this wild year.