You’ve probably seen them in old heist movies or maybe heard your grandfather mention a "pink" note he saw back in the fifties. It feels like an urban legend. In a world where most of us barely carry a twenty and tap our phones for everything from coffee to car payments, the idea of a single piece of paper being worth a grand seems almost mythical. But is there a $1,000 bill actually out there?

Yes. It is real. It is legal tender. And no, you won't find one at an ATM.

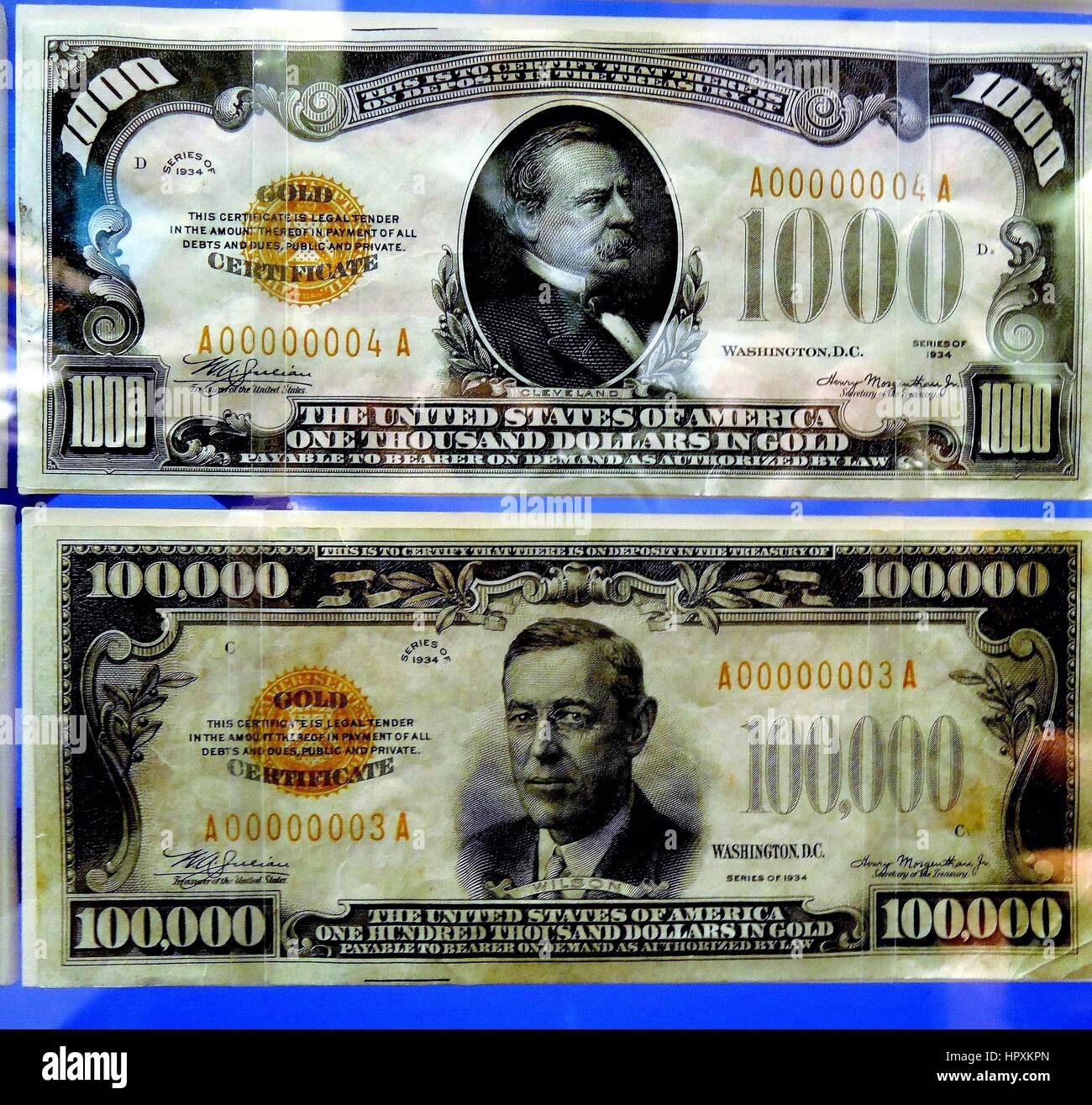

If you walked into a grocery store today and tried to buy a loaf of bread with a $1,000 bill featuring Alexander Hamilton (from the 1918 series) or Grover Cleveland (from the 1928 and 1934 series), the cashier would likely freeze. They’d probably call the manager. The manager might call the police. It’s not that the money isn’t "good"—it’s just that it hasn't been printed in eighty years. These high-denomination notes are relics of a time before wire transfers and credit cards, a time when moving large sums of money meant literally carrying a heavy bag of paper.

Why the $1,000 bill exists in the first place

Money used to be heavier. In the early 20th century, the Federal Reserve needed a way to move massive amounts of cash between banks without requiring a fleet of armored trucks for every transaction. If Bank A owed Bank B five million dollars, it was a lot easier to hand over 5,000 one-thousand-dollar bills than 50,000 hundred-dollar bills.

The most common version you’ll see in museums or private collections today is the Series 1934 $1,000 Federal Reserve Note. It features Grover Cleveland, the 22nd and 24th President of the United States. Before him, Alexander Hamilton graced the 1918 large-size note. It's kinda funny that Hamilton got demoted to the $10 bill later on, but that’s just how the Treasury rolls.

These bills weren't really for "regular" people. Sure, a wealthy person might use one to buy a house or a high-end Packard, but for the average worker earning $1,500 a year in the 1930s, seeing a $1,000 bill was about as likely as seeing a unicorn in the backyard. They were tools for the elite and the institutional.

The day the big bills died

On July 14, 1969, the Department of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve System made a quiet but massive announcement. They were officially discontinuing the use of the $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000 bills.

Why?

Basically, the government realized that big bills were a gift to organized crime. If you’re trying to move a million dollars in illicit cash, doing it in $100 bills requires a suitcase that weighs about 22 pounds. If you do it in $1,000 bills, you can fit that same million into a small envelope that weighs just over two pounds. It’s the ultimate "bad guy" convenience.

By the late 1960s, the rise of electronic banking made these high-value notes redundant for legitimate businesses. The Fed stopped printing them in 1945, but they didn't officially start pulling them out of circulation until 1969. Once they hit a bank, they are sent back to the Treasury and destroyed. They are "retired" in the most literal sense.

What is a $1,000 bill worth now?

If you find one in a dusty attic, do not—I repeat, do not—take it to the bank and deposit it.

Technically, a bank must accept it at face value. They will give you $1,000 for it. But you would be throwing away thousands of dollars in profit. Because these notes are so rare, their "numismatic" value (the collector value) is way higher than the number printed on the corners.

✨ Don't miss: Malawi Kwacha to USD: Why the Exchange Rate is Finally Stabilizing

Even a "beater"—a $1,000 bill that’s been folded, stained, or slightly torn—usually sells for at least $2,500 to $3,500. If you have one in pristine, "uncirculated" condition? You’re looking at **$5,000 to $10,000** or more at auction. There’s a specific kind of collector who obsesses over the "Gold Seal" 1928 series or the "Green Seal" 1934 series, and they are willing to pay a massive premium for the privilege of owning a piece of American history.

How to tell if yours is real (or just a movie prop)

Fake $1,000 bills are everywhere. Most of them are "play money" or novelty items sold in gift shops. Real ones have very specific markers:

- The Paper: It’s not actually paper. It’s a blend of 75% cotton and 25% linen with tiny red and blue security fibers embedded in it. If it feels like a regular printer sheet, it’s a fake.

- The Portrait: Grover Cleveland should look crisp. On many fakes, the eyes look "dead" or the fine lines in the hair are blurred.

- The Serial Numbers: They should be perfectly aligned and have a distinct "ink bite" into the paper.

- The Treasury Seal: On the 1934 series, this is usually a vivid green.

The $100,000 bill: The one you can't own

While we're talking about giant money, we have to mention the "Big Kahuna." The U.S. actually printed a $100,000 Gold Certificate in 1934. It features Woodrow Wilson.

However, you can’t have one. Honestly. It is illegal for a private citizen to own one. These were never intended for public circulation; they were used only for transactions between Federal Reserve Banks. They were backed by gold held by the Treasury. If you ever see one for sale on eBay, it’s 100% a counterfeit or a scan. The only ones left are held by the Smithsonian and the Federal Reserve Banks.

The future of high-denomination currency

Will we ever see a new $1,000 bill? Don't bet on it.

If anything, the world is moving in the opposite direction. There is constant chatter among economists and politicians about eliminating the $100 bill. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has been a vocal advocate for this, arguing that getting rid of the $100 would make it harder for tax evaders and drug cartels to operate. In Europe, the "Bin Laden" note—the €500 bill—was discontinued for exactly this reason.

In a digital economy, high-value physical cash is seen as a liability by the state. It represents "untracked" wealth. While some people argue that big bills would help hedge against inflation (since $100 doesn't buy what it used to), the government’s desire to monitor financial flows almost guarantees that the $1,000 bill will remain a ghost of the past.

How to actually find one

If you're dying to see one in person, your best bet isn't a bank—it's a high-end coin shop or a major currency auction like those held by Heritage Auctions or Stacks Bowers.

You can also visit the Museum of American Finance in New York (though you should check their current exhibit status) or the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington D.C. They have these notes on display so you can gawk at them without having to spend $4,000 to own one.

Actionable Next Steps for Collectors and the Curious

If you’ve stumbled across what you think is a $1,000 bill, or if you’re looking to invest in one, follow this checklist to avoid getting burned:

- Check the "Seal" and Series: Look at the bottom left or right of the portrait. If it says "Series 1934" or "Series 1928," you're in the right ballpark. If it says "Series 2021," you have a novelty item.

- Get a "PMY" or "PCGS" Grading: If you think the bill is real, do not handle it with your bare hands more than necessary. Oil from your skin can degrade the paper. Send it to a professional grading service like Paper Money Guaranty (PMG). A graded note is worth significantly more because the authenticity is guaranteed.

- Search the Serial Number: Some collectors look for "fancy" serial numbers (all the same digit, or low numbers like 00000005). These can double or triple the value of an already expensive bill.

- Avoid the "Bank Trap": If you take it to a standard commercial bank, they are trained to identify "non-circulating" currency. They will take the bill, give you $1,000, and it will be sent to the Fed to be shredded. You will lose the collector premium instantly.

- Research Recent Auctions: Before buying or selling, check sites like eBay "Sold" listings or professional auction archives to see what similar notes are actually selling for right now. Market prices fluctuate based on the economy and collector demand.

The $1,000 bill is a fascinating piece of financial history that reminds us of a time when "cash was king" in a much more literal sense. While it’s no longer part of our daily lives, its status as legal tender ensures it remains one of the most sought-after treasures in the world of paper money. Just don't try to use it at the self-checkout lane.