Isambard Kingdom Brunel was a man who didn't understand the word "impossible." Honestly, that’s probably why the SS Great Western exists at all. In the 1830s, people thought crossing the Atlantic by steam alone was a suicide mission for your wallet. They figured a ship would have to be so packed with coal to make the trip that there wouldn’t be any room left for passengers or actual cargo. Dr. Dionysius Lardner, a popular science "expert" of the day, famously claimed that a direct steam voyage from New York to Liverpool was as perfectly chimerical as a voyage to the moon.

He was wrong. Brunel proved it.

The SS Great Western wasn't just a boat; it was a giant middle finger to the scientific establishment of the 19th century. When it launched in 1837, it was the largest passenger ship in the world. But size wasn't the point. The point was the math. Brunel realized that while a ship's capacity increases by the cube of its dimensions, the resistance it faces in the water only increases by the square. Basically, bigger ships are more efficient. It sounds simple now, but back then, it was a revolution that changed global trade forever.

The Race That Almost Ended in Flames

The start of the SS Great Western's career was pure chaos. It was built in Bristol by the Great Western Steamship Company, specifically to extend the Great Western Railway all the way to New York. But a rival company, the British and American Steam Navigation Company, was desperate to beat them to the punch. They chartered a smaller steamer called the Sirius just to get there first.

It was a total underdog story, but a dangerous one.

The Sirius left Cork, Ireland, on April 4, 1838. The SS Great Western followed four days later from Avonmouth. It should have been an easy win for Brunel, but a fire broke out in the engine room during the initial leg from London to Bristol. It was bad. Brunel himself was injured, falling twenty feet after a ladder charred by the fire gave way. The ship had to be beached, repairs were rushed, and by the time it finally set off for New York, the Sirius had a massive head start.

The Sirius actually made it first, but barely. They ran out of coal and supposedly had to burn cabin furniture and spare masts just to keep the engines turning. They arrived in New York on April 22. The SS Great Western arrived the very next morning.

📖 Related: Is Social Media Dying? What Everyone Gets Wrong About the Post-Feed Era

Here is the kicker: the SS Great Western still had 200 tons of coal left in its bunkers.

It didn't just cross the Atlantic; it did it with ease. It proved that steam could be reliable, profitable, and—most importantly—predictable. While the Sirius was a one-off stunt, Brunel’s ship was a blueprint for the future of the travel industry.

Why the Design of the SS Great Western Actually Worked

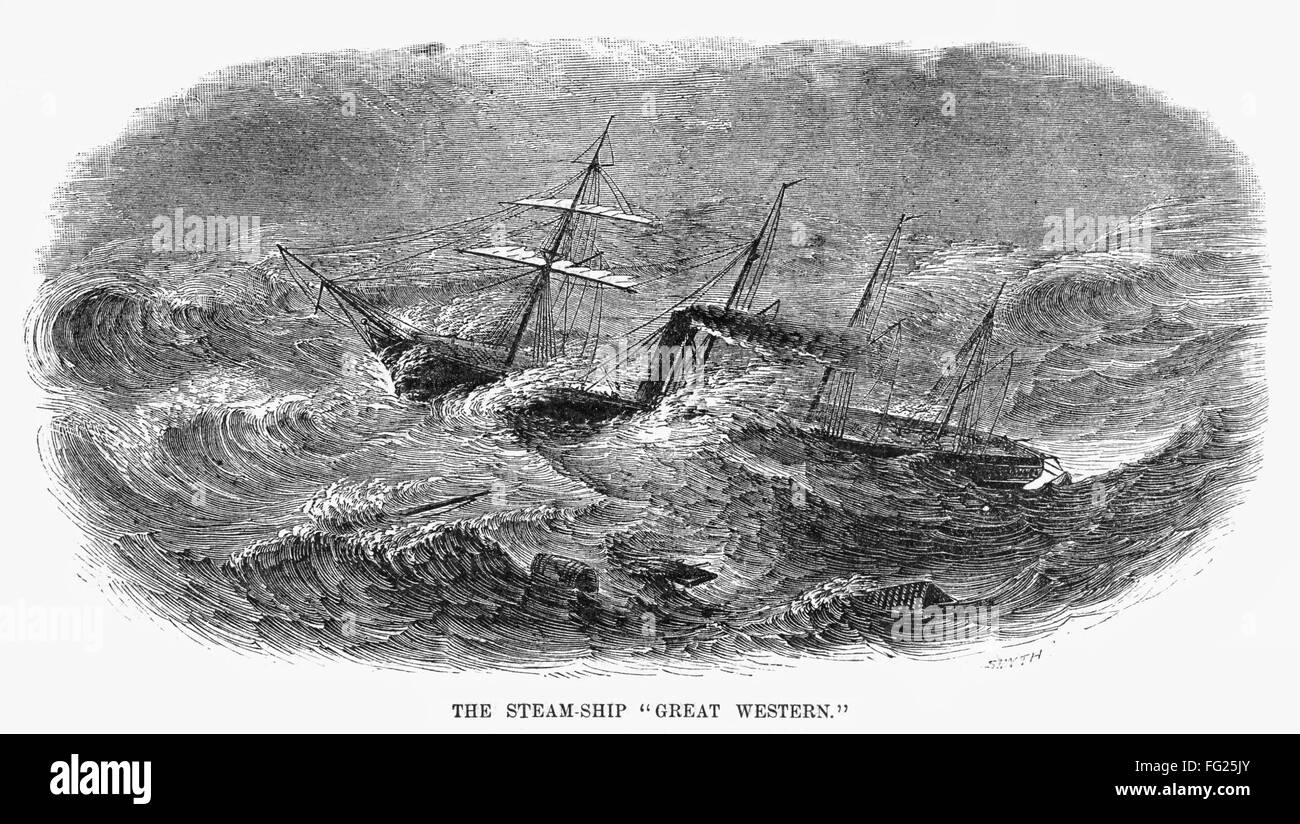

Most people look at old ship drawings and just see a wooden hull with some paddles. Look closer. The SS Great Western was a hybrid. It was a wooden-hulled paddle wheel steamer, but it was reinforced with iron diagonals. This thing was built like a tank.

- The Engines: It used side-lever engines built by Maudslay, Sons & Field. These were the workhorses of the era.

- The Hull: It was 236 feet long. At the time, that was gargantuan.

- The Power: It could hit about 8 or 9 knots. That sounds slow, but compared to a sailing ship at the mercy of the wind? It was a warp-speed jump in consistency.

One thing people get wrong is thinking this was an "iron ship." It wasn't. That came later with the SS Great Britain. The SS Great Western was the bridge between the old world of oak and the new world of iron and coal. It used four masts just in case the engines failed, which tells you a lot about the anxiety of the era. Sailors didn't trust engines yet. They saw them as loud, vibrating, soul-sucking machines that might explode at any second.

Life on Board: Not Exactly a Luxury Cruise

If you think a modern cruise is cramped, 1838 would have been a nightmare for you. The SS Great Western could carry about 128 passengers and 20 servants. The "Main Saloon" was the heart of the ship, decorated in a style that can only be described as "Victorian Excess." Think gold leaf, heavy drapes, and a lot of dark wood.

But it wasn't all fancy dinners.

👉 See also: Gmail Users Warned of Highly Sophisticated AI-Powered Phishing Attacks: What’s Actually Happening

The vibration from the paddle wheels was constant. The smell of burning coal and hot oil permeated everything. And then there’s the Atlantic itself. The North Atlantic is a mean stretch of water. In a wooden ship, even one as sturdy as this, you felt every single wave. There were reports of passengers being thrown from their berths during storms. Yet, people lined up to pay for it because it was fast. It shaved weeks off the crossing time.

Time, then as now, was money.

The Business Failure of a Technical Triumph

You’d think a ship this successful would make everyone rich. It didn’t. The SS Great Western was a victim of bad timing and aggressive competition. While Brunel was busy being a genius, a man named Samuel Cunard was busy being a businessman. Cunard secured the British government contract for trans-Atlantic mail.

That was the death blow.

The mail subsidy provided a guaranteed income that the Great Western Steamship Company simply couldn't match. Brunel’s company eventually collapsed under the weight of its own ambition. They spent too much money on the next project—the SS Great Britain—and the SS Great Western was eventually sold off to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company in 1847.

It spent the rest of its life working routes to the West Indies and even served as a troopship during the Crimean War. It was eventually broken up at Vauxhall in 1856. It’s a bit of a sad end for a ship that basically invented the modern Atlantic crossing. No museum. No preservation. Just scrap wood and recycled iron.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Apple Store Naples Florida USA: Waterside Shops or Bust

Common Misconceptions About the Great Western

A lot of amateur historians confuse this ship with its younger, bigger siblings.

- It wasn't the first to cross. As mentioned, the Sirius beat it by hours. But the Sirius wasn't a "trans-Atlantic steamship" in any practical sense. It was a coastal steamer that got lucky.

- It wasn't made of iron. That’s a huge one. People see "Brunel" and "Steam" and assume iron. The SS Great Western was one of the last great wooden masterpieces.

- It didn't use a propeller. It used massive paddle wheels on the sides. Screw-propulsion didn't become the standard until Brunel’s next ship proved it worked.

The SS Great Western was the "Proof of Concept." It proved Dr. Lardner was a blowhard and that the Atlantic was no longer an obstacle, but a highway. Without this specific ship, the massive waves of immigration in the 1840s and 50s would have looked very different. It made the world smaller.

What We Can Learn From Brunel’s Gamble

Engineering is often about the courage to look at a "proven" fact and ask if the person who said it was actually just guessing. Brunel knew the physics of displacement and fuel consumption better than the "experts" of his day. He didn't just build a ship; he built a system.

If you’re interested in the history of technology, the SS Great Western is a masterclass in scaling. It shows that sometimes, the solution to a problem isn't a new invention, but simply doing an old thing on a much larger, more calculated scale.

To really understand the impact of this ship, you have to look at the transition of Bristol as a port. The city invested heavily in the "Floating Harbour" to accommodate these giants. The infrastructure of entire cities changed because of one man’s desire to connect a railway to a boat. It was the birth of integrated transport.

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you want to see what's left of this legacy, you can't visit the SS Great Western itself, but you can do the next best thing.

- Visit the SS Great Britain in Bristol: This is the SS Great Western’s successor. It’s been perfectly restored and gives you a visceral sense of what Brunel was trying to achieve. You can actually stand under the dry dock and look at the hull.

- Check the Brunel Archives: The University of Bristol holds a massive collection of original drawings and letters. Seeing the actual calculations Brunel did for the coal consumption of the Great Western is wild.

- Explore the Being Brunel Museum: Located right next to the SS Great Britain, it offers a deep look into the man’s psyche—including his failures, which are just as interesting as his wins.

The SS Great Western might be gone, but the idea of the "regularly scheduled crossing" is something we take for granted every time we book a flight or check a shipping container’s ETA. It all started with a wooden boat, a lot of coal, and an engineer who refused to listen to the "experts."

The ship didn't just carry people; it carried the future. It proved that the ocean wasn't a barrier to technology, but a stage for it. When the ship was finally broken up, it wasn't because it had failed, but because it had succeeded so thoroughly that it made itself obsolete. New, bigger, faster ships were already taking its place, all built on the lessons Brunel learned between 1837 and 1838. That is the ultimate legacy of any great piece of tech: being the foundation for everything that comes next.