If you’ve spent any time on the internet since 2022, you’ve seen the flame wars. Fans are screaming about lore. Purists are clutching their copies of The Silmarillion. Everyone seems to have a different opinion on whether the show is a masterpiece or a total betrayal. But beneath all the noise, one question keeps popping up for casual viewers: is Rings of Power based on a book, or did Amazon just make the whole thing up?

The answer is actually kind of a legal nightmare.

Most people assume that because it’s Middle-earth, it must be an adaptation of a specific novel, like The Fellowship of the Ring. It’s not. It’s also not based on The Silmarillion, even though that’s the book that actually covers the history of the Second Age. It sounds crazy, right? Why would you spend nearly a billion dollars on a show and not even buy the rights to the main book covering that era?

Well, the Tolkien Estate is famously protective. To understand what’s on your screen, you have to understand the weird, fragmented world of J.R.R. Tolkien’s publishing history.

What Amazon actually bought (and what they didn't)

Let’s get the technical stuff out of the way first. When we ask is Rings of Power based on a book, the literal answer is: yes, but only about 150 pages of one.

Amazon does not own the rights to The Silmarillion. They don't own Unfinished Tales. They definitely don't own The History of Middle-earth series. What they do own are the TV rights to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. That's it.

But wait. The Lord of the Rings is set in the Third Age, and the show takes place thousands of years earlier in the Second Age. How does that work?

Basically, Tolkien included a massive set of appendices at the end of The Return of the King. Specifically, "Appendix A" (Annals of the Kings and Rulers) and "Appendix B" (The Tale of Years). These appendices act as a chronological "greatest hits" of Middle-earth history. They provide timelines, brief summaries of wars, and lineage charts. This is the "book" the show is based on. It’s essentially a 50-page outline of five thousand years of history.

Think of it like trying to write a six-season TV drama based on a Wikipedia timeline of the Roman Empire. You have the dates. You know who died and when. But you don't have the dialogue. You don't have the internal thoughts. You don't have the "small" moments that make a story feel real.

Filling in the gaps of the Second Age

Because the source material is so thin, the showrunners, J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay, have to invent a massive amount of "connective tissue." This is where the controversy starts.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

When you read Appendix B, you’ll see a line like: "1500: The Elven-smiths instructed by Sauron reach the height of their skill. They begin the forging of the Rings of Power."

That’s it. That’s the whole "source."

The show has to figure out: Who were these smiths besides Celebrimbor? What did they eat? What were they joking about before Sauron showed up? Since the writers can’t use material from The Silmarillion—which actually goes into detail about these characters—they have to create new characters or "remix" existing ones in a way that doesn't violate the copyright held by the Tolkien Estate.

It’s a tightrope walk.

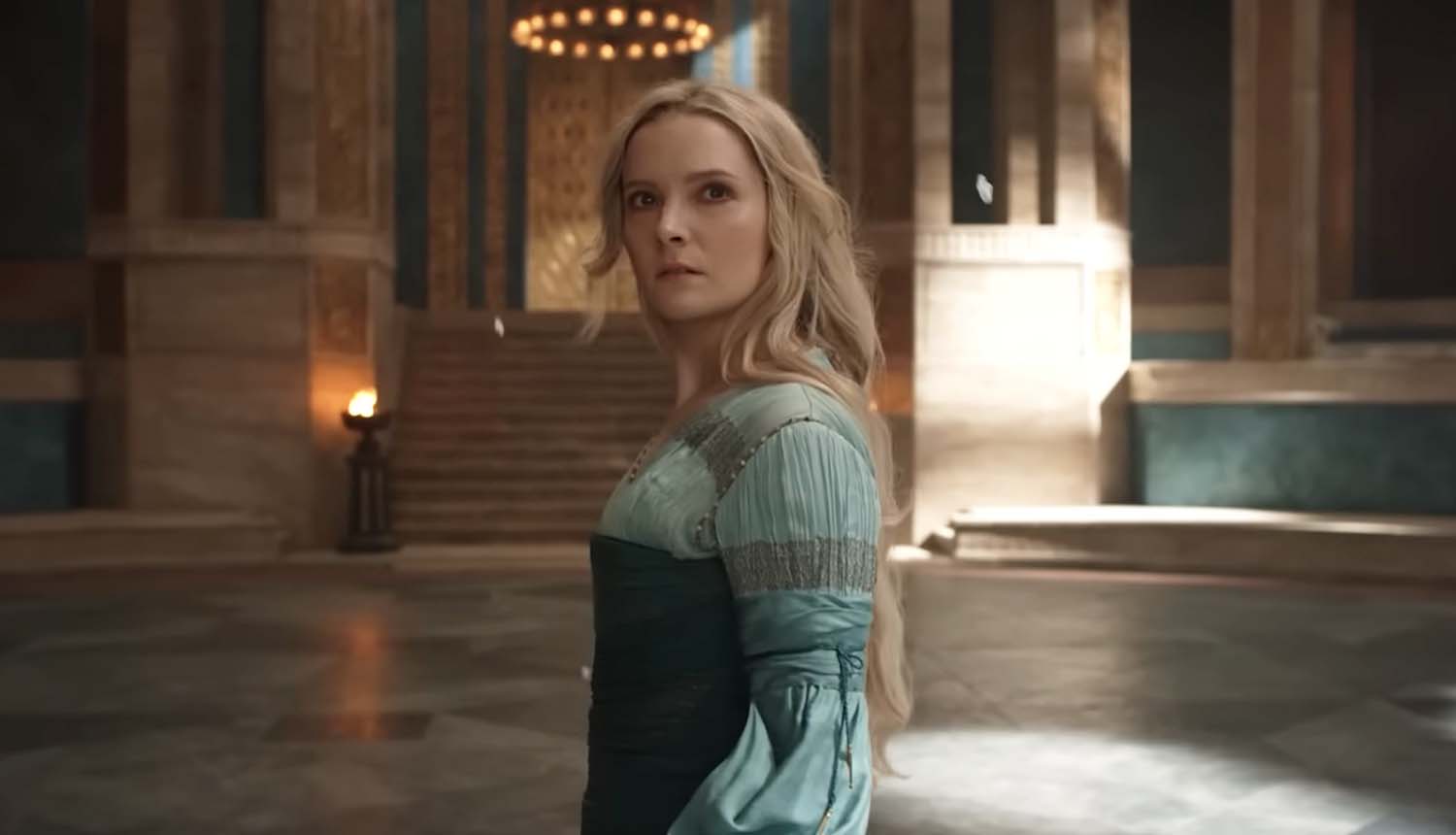

Take the character of Galadriel. In the books, her Second Age activities are... vague. Tolkien changed his mind about her story several times throughout his life. In some versions, she’s a warrior; in others, she’s more of a traditional ruler. The show chose the warrior path. Some fans hate it. Others think it fits the "vibe" of her being a rebel who stayed in Middle-earth against the wishes of the Valar.

Then you have characters like Nori Brandyfoot or The Stranger. They aren’t in any book. Period. The Harfoots are mentioned in the prologue of The Lord of the Rings as an early breed of hobbits, but their specific adventures in the Second Age are entirely a creation of the show.

Why they couldn't just buy The Silmarillion

You might be wondering why Amazon—the company that has literally all the money—didn't just buy the rights to the "real" book.

It wasn't about the price tag.

The Tolkien Estate, led for decades by Christopher Tolkien (the Professor’s son), has a very complicated relationship with Hollywood. Christopher famously disliked Peter Jackson’s films, feeling they turned his father’s philosophical epic into an action movie for teenagers. After he stepped down, the Estate became more open to deals, but they still won't sell the "Crown Jewels."

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

The Silmarillion is the Bible of Middle-earth. It’s sacred.

By only selling the rights to the Appendices, the Estate keeps a level of control. They actually have "lore experts" on the production team to make sure Amazon doesn't stray too far. If Amazon wanted to make Galadriel an undercover Orc, the Estate would veto it. They allow "expansion," but they generally prevent "contradiction."

The "Time Compression" Problem

One of the biggest differences between the book and the show is how time works. If you look at the actual timeline in the book, the events of the Second Age are spread out over 3,441 years.

In the books:

- The Rings are forged.

- About 1,500 years pass.

- Isildur is born.

- The Last Alliance happens.

If the show followed the book exactly, every human character would die of old age every two episodes. Elrond and Galadriel would be the only ones left.

To make it a TV show, Amazon compressed everything. They made it so the forging of the rings and the fall of Númenor are happening almost simultaneously. For a book reader, this is jarring. It’s like watching a movie about the American Revolution where George Washington is also fighting in the Civil War. But for a TV audience, it’s the only way to keep the stakes high for the human characters we’ve grown to like.

Is the lore being "broken"?

This is the billion-dollar question.

Honestly, it depends on how you define "lore." If you mean "every single date must match Appendix B," then yes, the show breaks the lore constantly.

But if you mean "does it capture the spirit of Tolkien’s themes," that’s up for debate. Tolkien wrote a lot about "sub-creation"—the idea that others would eventually come and add to his mythology. He once wrote that he wanted to leave room for "other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama."

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

He probably didn't expect those "other hands" to be a massive tech corporation, but the principle is there.

The show gets the big things right:

- Sauron is a deceiver who uses people’s good intentions against them.

- The Elves are fading and desperate to hold onto the past.

- The Men of Númenor are obsessed with death and immortality.

- Dwarves are proud, stubborn, and deeply connected to the stone.

Whether or not those things are enough to make it "Tolkien" is something fans will be arguing about until the Fourth Age.

What you should read if you want the "Real" story

If you’ve watched the show and you’re still asking is Rings of Power based on a book because you want more, you have a few options.

First, go read the Appendices at the back of The Return of the King. Seriously. It’s better than it sounds. It’s like reading a history book written by an Elven scholar.

Second, if you want the deeper, darker version of the Sauron/Annatar story, read the "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age" section at the very end of The Silmarillion. It’s only about 30 pages long, but it contains more "epic" moments than most trilogies.

Finally, check out The Fall of Númenor. This is a relatively new book (edited by Brian Sibley) that actually collects all of Tolkien’s Second Age writings into one chronological volume. It’s the closest thing you’ll get to a "script" for the show, even if the show ignores half of it.

How to navigate the Middle-earth "Canon"

Middle-earth isn't like Star Wars or Marvel. There is no "official" canon database because Tolkien himself was constantly changing the rules. He would write a story in 1930, change it in 1950, and then write a letter in 1970 saying both versions were wrong.

When you watch the show, just remember that it is a "version" of the story. It’s an interpretation based on a very specific, limited set of rights.

Actionable Next Steps for the Curious Viewer

- Read the Appendices: Don't skip them next time you finish the trilogy. Appendix B is your roadmap for everything Amazon is doing.

- Identify the "New" Characters: Keep a mental list of who is "Original" (like Arondir, Bronwyn, and Adar) versus who is "Canon" (like Gil-galad, Elendil, and Pharazôn). It helps you understand where the writers have freedom and where they are constrained.

- Listen to the Score: Bear McCreary actually used different musical themes to represent the "cultures" Tolkien described. The music often follows the "book" vibes better than the dialogue does.

- Look for the Easter Eggs: The show is full of nods to The Silmarillion that they can't explicitly name for legal reasons. For example, the statues in Númenor or the mentions of the "Old Days" are often subtle nods to stories Amazon doesn't technically own the rights to.

- Compare the Map: Tolkien was a map nerd. The map used in the show is one of the most "accurate" things about it. Compare the show's map to the one in your book to see exactly where the characters are traveling across the massive continent of Middle-earth.

Ultimately, the show is a bridge. It’s a way for people who haven't spent forty years reading scholarly footnotes to experience the scale of Tolkien’s world. It’s not a replacement for the books—nothing ever could be—but it’s a fascinating look at what happens when you try to turn a historical timeline into a modern drama.

Whether you love it or hate it, the fact that we're still talking about what happened in the Second Age is a testament to the world Tolkien built. He created a history so rich that people are willing to spend billions of dollars just to see a few snippets of it brought to life.