You’re standing in the garden or the produce aisle, eyeing those vibrant, ruby-red stalks. They look delicious. They look like the backbone of a perfect summer crumble. But then that nagging voice in the back of your head pipes up with a warning your grandmother probably gave you: "Don't touch the leaves." It makes you wonder, is rhubarb poisonous to humans, or is that just one of those old wives' tales meant to keep kids from eating raw veggies?

Honestly, it’s a bit of both.

Rhubarb is a botanical contradiction. On one hand, the stalks are a tart, fiber-rich staple of British and American baking. On the other, the broad, fan-like leaves contain a chemical cocktail that could genuinely land you in the hospital—or worse, if you were particularly determined to eat a salad's worth of them.

The Chemistry of Why Rhubarb Leaves Can Be Dangerous

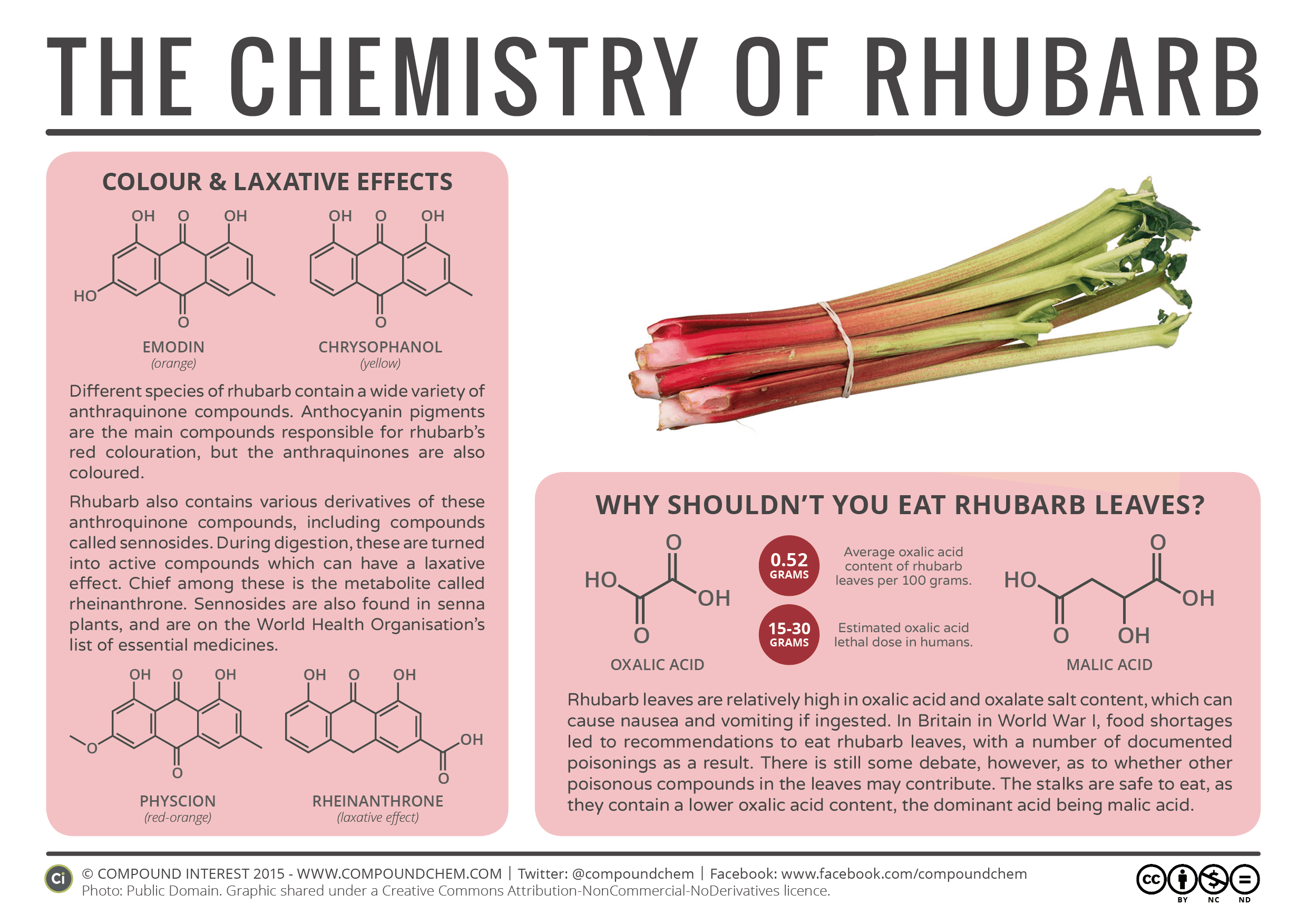

The primary villain here is oxalic acid. It’s a naturally occurring compound found in plenty of healthy foods, including spinach, beets, and almonds. However, in rhubarb leaves, the concentration is significantly higher. But it isn't just the oxalic acid doing the dirty work. Scientists have also identified anthraquinone glycosides in the leaves, which act as potent purgatives. Basically, if the acid doesn't get you, the digestive distress will.

When you ingest high levels of oxalic acid, it binds with calcium in your body. This creates calcium oxalate crystals. Imagine tiny, microscopic shards of glass floating through your bloodstream. These crystals have a nasty habit of settling in the kidneys, which is why the biggest risk of rhubarb leaf poisoning isn't instant death, but rather acute kidney failure.

It’s a dose-dependent poison.

A single bite of a leaf might just leave you with a gritty feeling on your teeth and a very sour taste in your mouth. To actually reach a lethal dose, a grown adult would likely need to consume between 10 and 15 pounds of the leaves. That sounds like a lot—and it is—but "poisonous" doesn't always mean "deadly." Even small amounts can trigger nausea, vomiting, and a burning sensation in the throat.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth Behind RFK Autism Destroys Families Claims and the Science of Neurodiversity

How to Spot the Symptoms of Rhubarb Poisoning

Let’s say the unthinkable happens. Maybe a pet gets into the compost bin, or a toddler decides the big green leaves look like lettuce. What actually happens to the body?

Usually, the first sign is immediate irritation. The mouth and throat start to burn. This is the calcium oxalate crystals physically irritating the mucous membranes. It’s your body’s way of saying, "Stop eating this immediately."

If someone persists and swallows a significant amount, the symptoms escalate:

- Difficulty breathing as the throat swells.

- Intense abdominal pain and cramping.

- Vomiting and diarrhea (thanks to those anthraquinones).

- Weakness or a "fuzzy" feeling in the limbs.

- Red-tinted urine, which is a massive red flag for kidney distress.

If you see someone exhibiting these signs after eating garden greens, skip the home remedies. Call poison control. According to data from the National Capital Poison Center, most cases are managed successfully with supportive care, but the risk of permanent kidney damage is real if the dose is high enough.

The World War I "Rhubarb Leaf" Disaster

History gives us a grimly fascinating look at why we take this seriously. During World War I, the British government recommended rhubarb leaves as a food source to combat national shortages. It seemed like a good idea at the time. "Don't waste any part of the plant!" was the mantra of the day.

It was a disaster.

🔗 Read more: Medicine Ball Set With Rack: What Your Home Gym Is Actually Missing

Reports started trickling in of people falling violently ill. There were documented cases of deaths attributed to "rhubarb leaf poisoning" during this period. One specific case often cited in medical literature involved a man who ate a large portion of cooked leaves and died shortly after from what we now recognize as the systemic effects of oxalate poisoning. This historical blunder is largely why the "rhubarb is poisonous" warning became so deeply ingrained in Western culinary culture.

Can the Stalks Ever Be Poisonous?

This is where things get interesting for the home gardener. We know the leaves are bad. We know the stalks are good. But what about the middle ground?

There is a common belief that if rhubarb is hit by a hard frost while still in the ground, the toxins from the leaves can "migrate" down into the stalks. Is this true? Sort of.

When a plant freezes, the cell walls rupture. This can cause the oxalic acid in the leaves to leach into the stalks. If your rhubarb patch looks wilted, black, and mushy after a late spring freeze, do not eat it. The stalks might not kill you, but they will likely contain much higher levels of oxalates than usual, leading to a very unhappy stomach. If the stalks are still firm and upright after a light frost, they are generally considered safe, but the "if it's mushy, toss it" rule is a solid one to live by.

Common Misconceptions About Rhubarb Color

People often think red stalks are safe and green stalks are poisonous. This is 100% false.

The color of a rhubarb stalk is determined by the variety of the plant, not its toxicity or even necessarily its ripeness. Some of the most delicious heirloom varieties, like 'Victoria,' stay mostly green with just a blush of red at the base. You can eat green stalks all day long without any ill effects. In fact, some professional chefs prefer the green varieties because they tend to be more productive and have a slightly more assertive tartness.

💡 You might also like: Trump Says Don't Take Tylenol: Why This Medical Advice Is Stirring Controversy

Rhubarb and Kidney Stones: A Real Connection

Even if you only eat the stalks, there is a legitimate health concern for a specific group of people. If you are prone to calcium oxalate kidney stones, you might want to treat rhubarb like a "sometimes" food.

Because the stalks still contain some oxalic acid (though much less than the leaves), eating large quantities can increase the oxalate levels in your urine. For most people, the kidneys handle this just fine. For stone-formers? It’s like adding fuel to a fire.

If you can't resist a strawberry rhubarb pie, try pairing it with a glass of milk or some ice cream. The calcium in the dairy binds with the oxalates in your stomach before they ever reach your kidneys. It's a delicious way to do some proactive harm reduction.

Handling Rhubarb Safely in Your Kitchen

You don't need a hazmat suit to prep rhubarb. Just follow some basic logic.

- Trim immediately: When you harvest or buy rhubarb, cut the leaves off and discard them. Don't leave them attached in the fridge; they can make the stalks go limp faster.

- Compost with care: You can actually compost rhubarb leaves! The oxalic acid breaks down during the composting process and won't poison your future tomatoes. However, if you have curious dogs who like to dig in the compost, bury the leaves deep or put them in a closed bin.

- Wash thoroughly: Just like any other vegetable, give the stalks a good scrub to remove dirt and any residual leaf bits.

Practical Steps for the Safe Rhubarb Lover

Rhubarb is a nutritional powerhouse when handled correctly. It’s loaded with Vitamin K1, which is essential for blood clotting and bone health. It’s also a great source of fiber. To enjoy it without the "is rhubarb poisonous" anxiety, keep these actionable tips in mind:

- Stick to the Stalk: Never, under any circumstances, experiment with cooking the leaves. There is no "safe" way to prepare them.

- Watch the Frost: If a freeze hits your garden, wait for new, firm growth to emerge before harvesting again. Discard the frost-damaged stalks.

- Know Your Body: If you have a history of kidney disease or stones, talk to your doctor about your oxalate intake.

- Variety Matters: If you’re planting a garden, look for varieties like 'Crimson Red' or 'Holstein Bloodred' if you want that classic look, but don't be afraid of the green ones.

Rhubarb is a unique, tart, and wonderful plant that has earned its place in our kitchens. It isn't a "hidden killer" waiting to get you, but it does demand a certain level of respect. Treat it right—discard the leaves, watch for frost, and maybe add a little extra sugar—and you’ll be perfectly safe.