You’ve felt it. That crisp, bitey air that makes your nostrils sting the second you step onto the porch in January. It feels heavy, doesn't it? Like the air itself is pushing down on the pavement. Most of us grew up hearing that "heat rises," so it stands to reason that when things get freezing, everything must be sinking. But then you look at a weather map during a massive blizzard and see a giant "L" sitting right over the coldest part of the country.

So, is cold weather high pressure or low? Honestly, it’s both.

It depends entirely on whether you’re talking about a clear, bone-chilling Tuesday morning or a messy, slushy weekend storm. If you are standing in the middle of a dry, Siberian-style cold snap, you are almost certainly under a high-pressure system. If you are digging your car out of two feet of snow, you're dealing with low pressure. It’s a bit of a atmospheric contradiction that drives people wild when they try to plan their weekend hikes or understand why their joints ache more one day than the next.

The Heavy Truth About Cold, Dry Air

Physics is pretty blunt about this: cold air is denser than warm air. When air molecules get cold, they stop bouncing around like caffeinated toddlers and start huddling together. They take up less space. Because they are packed tighter, they get heavier. This heavy air sinks toward the ground.

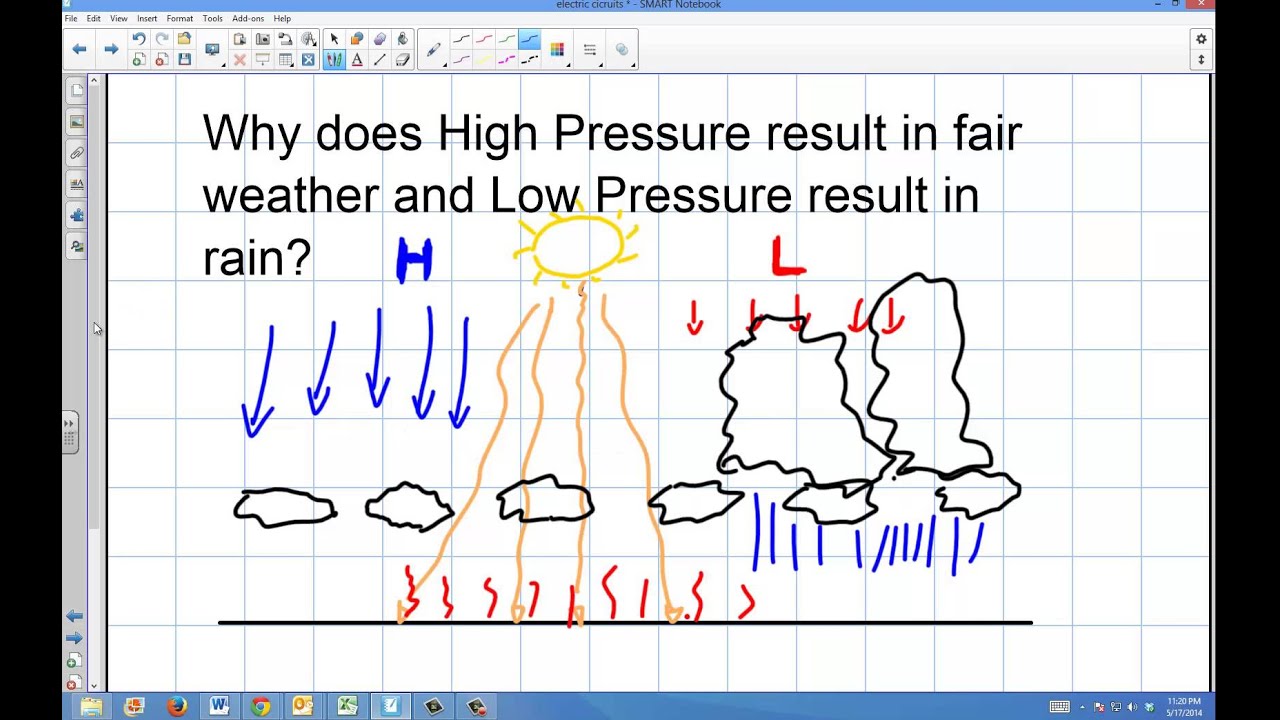

That sinking motion is the literal definition of high pressure.

When you see a "Blue H" on the evening news during winter, expect clear skies. Why? Because that sinking air acts like an invisible hand pushing down on the earth, preventing clouds from forming. Moisture can't rise to create the fluff you need for rain or snow. This is why some of the coldest places on Earth, like the Antarctic interior, are technically deserts. It is incredibly cold, and because the pressure is so high, it almost never actually snows. You get that "bluebird sky" weather—brilliant sun, blinding white ground, and a temperature that will freeze your coffee before you can finish it.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Why Low Pressure Brings the "Messy" Cold

Now, let's flip the script. If cold air is heavy and creates high pressure, why do we get low-pressure storms in the winter?

This is where the geography of the atmosphere gets messy. A low-pressure system—the "L" on the map—is basically a vacuum. It’s an area where air is rising. As that air rises, it cools down, and the moisture inside it condenses into clouds. If the surrounding environment is already freezing, that moisture turns into snow.

You’ve probably noticed that right before a big snowstorm, the temperature actually rises a little bit. It might go from 15°F to 28°F. That’s because the low-pressure system is pulling in air from elsewhere to fill the void. Often, it’s pulling in slightly "warmer" (relatively speaking) moist air from the ocean or the south.

So, while the storm itself is a low-pressure event, it’s the interaction between that low and a nearby high-pressure block that determines if you’re getting a light dusting or a catastrophic nor’easter. The pressure gradient—the "slope" between the high and the low—is what creates the wind. The steeper the difference in pressure, the faster the wind howls through your window seals.

The "Polar Vortex" Confusion

We can't talk about cold weather and pressure without mentioning the Polar Vortex. It’s become a buzzword, but most people get the mechanics backward.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

The Polar Vortex itself is actually a massive area of low pressure that stays perched over the North Pole. It’s a spinning cyclone of frigid air. When it’s strong, it stays put. But when the jet stream wavers—sort of like a spinning top starting to wobble—pieces of that cold air break off and slide south.

When that chunk of Arctic air hits the United States or Europe, it arrives as a high-pressure cell.

So, you have a low-pressure source (the vortex) sending out high-pressure messengers (the cold snaps). It’s a weird hand-off. National Weather Service meteorologists often track these "Arctic Highs" as they slide down from Canada. These systems are famous for "temperature inversions," where the cold, high-pressure air gets trapped at the surface while it's actually warmer a few thousand feet up on a mountain top.

Atmospheric Pressure and Your Body

It isn't just about the "weather out there." Your body feels these shifts.

Ever wonder why your grandpa could "feel" a storm coming in his knees? He wasn't crazy. When a low-pressure system moves in (bringing the cold snow), the air pressure drops. This means there is less pressure pushing against your body's tissues. This allows those tissues to slightly expand, which can put pressure on joints and nerves.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Conversely, the high-pressure cold—the clear, dry stuff—usually feels "better" for joints but worse for your skin and sinuses because the air is so incredibly dry.

The Role of Altitude

We also have to consider where you are standing. If you are in Denver, the air is naturally at a lower pressure than in Miami because there is less atmosphere "stacking" on top of you. However, the relative pressure still follows the same rules. A "High" in Denver will still be colder and clearer than a "Low" in Denver.

One fascinating exception to the "cold is high pressure" rule is the "Thermal Low." In some specific desert environments, you can get intense cold at night that doesn't immediately result in high pressure because the terrain traps heat or moves air in weird ways, but for 99% of the population, the rule of thumb remains:

- Clear, stable, brutal cold? High Pressure.

- Snowy, windy, "warmer" cold? Low Pressure.

What to Do With This Information

Knowing whether the cold is high or low pressure helps you actually survive the winter without losing your mind.

If the barometer is rising and you’re into a high-pressure cold spell, humidify everything. High pressure in winter is notoriously dry. This is when you get those painful static shocks from the carpet and your skin starts to crack. You need to focus on moisture—not just for your skin, but for your house. Dry air feels colder than moist air at the same temperature.

If the barometer is dropping and a low-pressure system is moving in, prep for the weight. Low pressure means snow. Unlike the "dry cold," this is a moisture event. Check your snow blower, salt the walk before the flakes start, and watch your tire pressure. Tires lose about 1 to 2 pounds of pressure for every 10-degree drop in temperature, regardless of whether it's a "High" or "Low" system.

Quick Winter Checklist Based on Pressure:

- Falling Pressure (The Low): Seal your windows now. The wind is coming. Get the shovel ready. The air will feel "heavy" and damp.

- Rising Pressure (The High): Crank the humidifier. Hydrate your skin. Expect the sun to be bright—grab your sunglasses, because "snow blindness" is a real thing when high-pressure sun hits a fresh snowpack.

- The Switch: The most dangerous time for ice is the transition. When a high-pressure cold dome starts to get pushed out by a low-pressure moist system, the "warm" air slides over the top of the cold air. This creates freezing rain. If you see the pressure starting to dip after a long cold snap, get off the roads.

The atmosphere is basically a giant balancing act. It’s always trying to move air from where there’s too much (High) to where there’s too little (Low). The cold is just the fuel that makes the engine move. Next time you see the "H" and "L" on the map, you'll know exactly which kind of coat—and which kind of attitude—you'll need for the day. High pressure means it's time to enjoy the sun but watch your skin; low pressure means it's time to hunker down and wait out the storm.