You’ve probably seen the anime tropes. A student opens their shoe locker only to find it stuffed with trash, or maybe their desk is covered in flowers—a grim Japanese symbol for death. It feels dramatic, almost stylized for TV. But if you’re asking is bullying in japan really bad, the answer isn't a simple yes or no. It’s complicated. It’s quiet. And honestly, it’s often more psychological than physical.

Japan calls it ijime.

This isn't just "kids being kids." In 2023, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) reported a record-breaking 681,948 cases of bullying across schools. That’s a staggering number. But here’s the kicker: experts think that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Many cases go unreported because of a cultural pressure to keep the peace.

The Quiet Nature of Ijime

In many Western countries, bullying is often loud. It’s a shove in the hallway or a fight behind the gym. In Japan, it’s usually about exclusion.

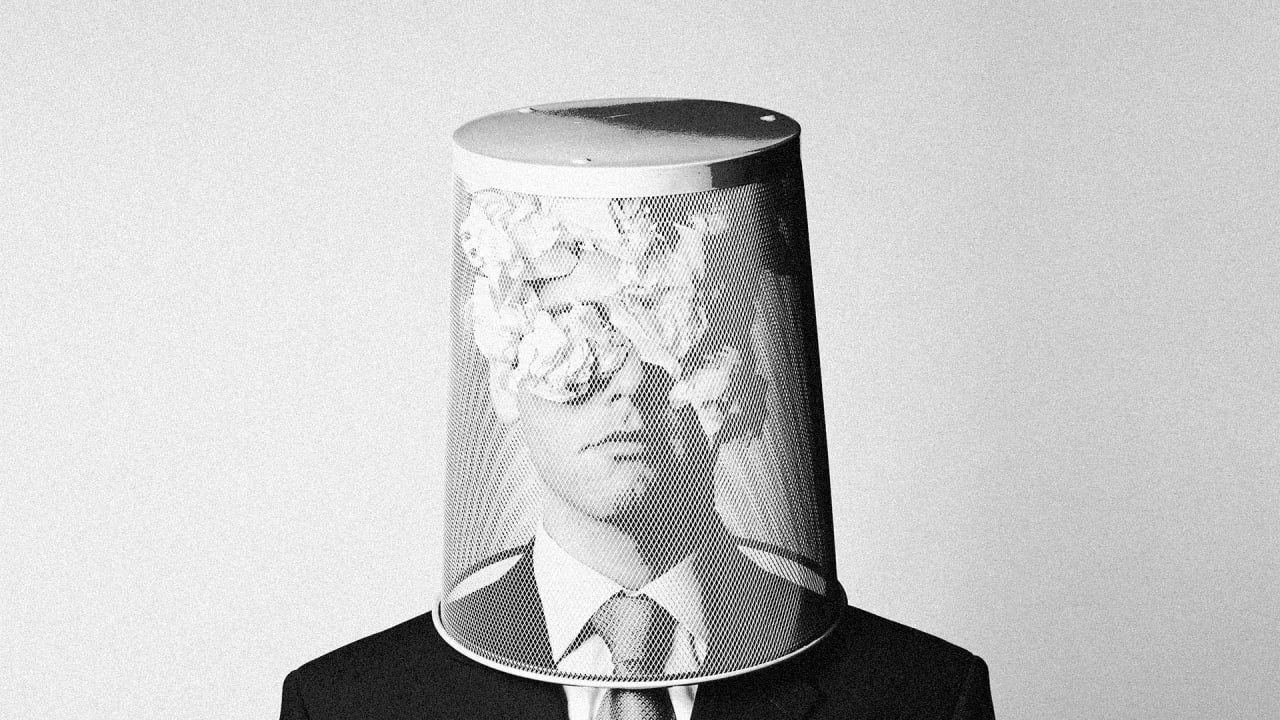

Mushi (ignoring) is one of the most common forms. Imagine walking into a classroom and every single person—people you’ve known for years—acts like you are invisible. You speak, no one answers. You sit down, and the circle moves away. It’s a surgical removal of a person from the social fabric.

This happens because Japanese society places a massive premium on wa, or harmony. There’s a famous proverb: "The nail that sticks out gets hammered down" (deru kugi wa utareru). If a student is too smart, too slow, too "foreign," or even just "too much," the group often corrects that deviation through collective shunning.

It’s psychological warfare.

The Ministry’s data shows that "mockery, insults, and being ignored" make up over 60% of reported cases. Physical violence is actually much lower on the list. But don't let that fool you into thinking it’s "lighter." The mental toll of being erased by your peers is a leading factor in futoko (school refusal) and, tragically, youth suicide rates which have hit record highs in recent years.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Why Teachers Sometimes Look the Other Way

Why don't the adults just stop it? You’d think a teacher seeing a kid being ignored would step in.

Sometimes they do. Often, they don't.

There’s a systemic issue here. Japanese teachers are notoriously overworked. They aren't just teaching math; they’re coaching clubs until 7:00 PM, doing administrative work, and managing the "moral education" of their students. Admitting there is bullying in their classroom can sometimes be seen as a failure of their leadership. In some documented cases, like the infamous 2011 Otsu City incident, the school and even the police initially dismissed the severity of the bullying before a student took his own life.

That specific case changed the law. In 2013, Japan passed the "Bullying Prevention Promotion Act." It forced schools to report "serious outcomes" to the government.

But laws don't change culture overnight.

Teachers still struggle with the "bystander" effect. In a classroom of 40 kids where 39 are ignoring one, the teacher might feel that "intervening" will only make the target stand out more. It’s a Catch-22. If the teacher singles out the victim for protection, they’ve just hammered the nail even harder.

The Rise of Giga-Ijime

Technology changed the game. It’s not just in the hallways anymore.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

Cyberbullying in Japan has its own flavor. It happens on LINE, the dominant messaging app. "LINE-hazushi" is a specific term for removing someone from a group chat or creating a secondary group specifically to talk trash about one person who isn't there.

It’s 24/7.

A student goes home to escape the classroom, but their phone is buzzing with the silence of a group they were kicked out of. MEXT statistics suggest that while physical bullying peaks in elementary school, cyberbullying and sophisticated social exclusion skyrocket in junior high.

Is Bullying in Japan Really Bad for Foreigners?

If you’re moving to Japan with kids, this is probably your biggest fear. Is it worse for "different" kids?

The data is mixed. "Hafu" (mixed-race) children or kikokushijo (returnees who lived abroad) often face a specific type of pressure. They might speak Japanese with an accent, or they might "read the air" (kuuki wo yomu) differently. In a system built on uniformity, any difference is a target.

However, many international schools in Tokyo or Osaka have vastly different cultures. The "really bad" bullying is most concentrated in the rigid environment of public local schools where the pressure to conform is absolute.

What’s Actually Being Done?

It’s not all doom and gloom. Japan is arguably more aware of this now than ever before.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

- Free Classrooms: Many wards now offer "educational support centers" or non-traditional schools for kids who can't handle the atmosphere of a regular school.

- Stop It Apps: Some prefectures have introduced anonymous reporting apps where students can send screenshots of cyberbullying directly to the Board of Education.

- Moral Education: The curriculum has been revised to focus more on empathy, though critics argue that "teaching" empathy from a textbook is a bit like teaching someone how to swim by reading a manual.

The Reality Check

So, is bullying in Japan really bad?

Compared to the US or the UK, you are far less likely to get your lunch money stolen or get beaten up in the bathroom. But you are far more likely to experience a soul-crushing isolation that the adults around you might describe as "just a misunderstanding."

The "badness" isn't in the violence; it's in the persistence and the collective nature of the act. When an entire group decides you don't exist, it’s hard to convince yourself otherwise.

Actionable Steps for Parents and Students

If you are navigating the Japanese school system and suspect ijime is happening, "waiting it out" rarely works.

- Document everything. Japanese bureaucracy runs on paper. Don't just say "they're mean." Save the LINE screenshots. Write down dates, times, and specific names.

- Use the "Serious Outcome" language. If you talk to a principal, use the phrase judai jitai (serious state of affairs). This triggers specific legal requirements under the 2013 Act that schools are often desperate to avoid.

- Look outside the school. If the school isn't helping, contact the Kodomo no Jinken 110-ban (Children’s Rights Hotline). They provide a layer of external pressure that schools actually listen to.

- Prioritize mental health over attendance. The rise of futoko (non-attendance) has lessened the stigma of staying home. If a child’s spirit is breaking, a diploma from that specific school isn't worth the cost. There are correspondence high schools and alternative paths that didn't exist twenty years ago.

The system is slowly shifting from "fix the child so they fit in" to "fix the environment so the child can breathe." But until that shift is complete, staying informed and being ready to pull the "emergency brake" on a toxic school situation is the most important thing any parent can do.

Resources for Support:

- Childline Japan: 0120-99-7777 (Toll-free, anonymous)

- TELL Japan: 03-5774-0992 (English language counseling and support)

- MEXT Consultation Hotline: 0120-0-78310 (24-hour bullying help)