It is a bit of a trick question. If you’re standing on a beach in Florida watching the palm trees bend toward the sand, you call it a hurricane. If you’re in Tokyo, it’s a typhoon. If you’re in Perth, it’s just a cyclone.

Basically, they are the same thing.

To be precise: is a hurricane a tropical cyclone? Yes. Every single hurricane is a tropical cyclone, but not every tropical cyclone is a hurricane. It’s a "square and rectangle" situation. A tropical cyclone is the broad scientific term for a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or subtropical waters. It has a closed low-level circulation. It’s fueled by the heat of the ocean. When that system gets fast enough—specifically hitting sustained winds of 74 miles per hour—it earns the title of "hurricane" in the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific.

Language is weird. Meteorology is weirder.

The Global Naming Game

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) doesn't just let people pick names for fun. There’s a strict geographic divide. If you see a massive swirling monster in the North Atlantic, the Northeast Pacific (east of the Dateline), or the South Pacific (east of 160°E), you are looking at a hurricane. This name actually comes from "Huracan," a Caribbean god of evil.

Shift your gaze to the Northwest Pacific. If that same storm threatens the Philippines or China, it’s a typhoon.

Then you have the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific. Over there, they don't bother with specific regional nicknames. They just call them tropical cyclones. Sometimes "severe tropical cyclones" if they're particularly nasty. It’s all the same physics, the same terrifying "eye," and the same destructive power. The only difference is the coordinate on your GPS.

How a Storm Graduates

Most people think these storms just appear. They don't. They have a lifecycle that looks more like a promotion track at a job. It starts as a tropical disturbance. This is just a cluster of thunderstorms with very little organization. It looks like a messy blob on satellite imagery.

Then comes the tropical depression. This is when the storm starts to rotate and the winds stay under 39 mph. Once those winds hit the 39 to 73 mph range, it becomes a tropical storm. This is a big deal because this is when the storm gets a name. Think Katrina, Ian, or Idalia.

Finally, if the wind hits $119$ kilometers per hour ($74$ mph), it becomes a hurricane.

Dr. Rick Knabb, a former director of the National Hurricane Center, often emphasizes that the category of the hurricane only tells you about the wind. It doesn't tell you about the water. This is where people get hurt. They see a "Category 1" and think it’s "just" a tropical cyclone. But a Category 1 can dump three feet of rain and cause a storm surge that destroys a neighborhood. The name is just a label for wind speed; it’s not a label for total danger.

Why the Physics Stay the Same

Whether it’s a hurricane or a cyclone, the "engine" is identical. It requires three main ingredients. Warm ocean water (at least 80°F). Moisture in the atmosphere. Low vertical wind shear.

Wind shear is the enemy of these storms. If the winds at the top of the atmosphere are blowing in a different direction than the winds at the bottom, they basically tilt the storm and rip it apart. It’s like trying to spin a top while someone is poking the top of it. It wobbles and dies. But when the conditions are perfect, the storm creates a feedback loop. Warm air rises, creates low pressure, more air rushes in, and the Coriolis effect (caused by Earth's rotation) starts the spinning.

Actually, that’s why you never see these storms on the equator. The Coriolis effect is zero at the equator. You need to be at least 5 degrees of latitude away from the equator for the storm to start spinning.

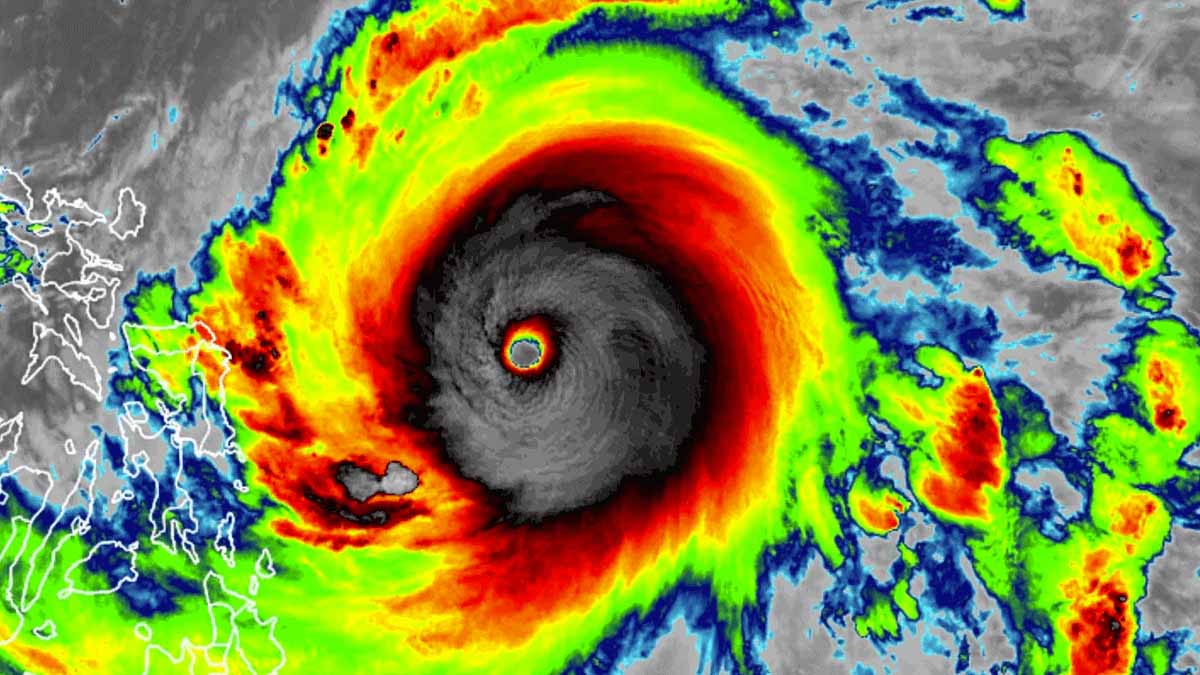

The "Eye" of the Confusion

There is a huge misconception that the "eye" is the only place where the storm is a "real" hurricane. Not true. The eye is actually the calmest part. It’s the eyewall—the ring of clouds immediately surrounding the center—where the highest winds live.

In 2023, we saw storms like Hurricane Otis undergo "rapid intensification." This is a nightmare scenario for forecasters. Otis went from a weak tropical storm to a Category 5 hurricane in almost no time before hitting Acapulco. This happens when the storm hits a pocket of incredibly deep, warm water and the wind shear vanishes. It proves that the transition from a general tropical cyclone to a major hurricane can happen in less than 24 hours.

🔗 Read more: Why the American War of Independence 1776 Was More Than Just Tea and Taxes

Climate Change and the New Normal

We aren't necessarily seeing more storms, but the ones we see are becoming more intense. The math is simple: warmer water equals more fuel. Research from organizations like NOAA and the IPCC suggests that while the total number of tropical cyclones might stay the same or even decrease slightly, the proportion of those that become high-end Category 4 and 5 hurricanes is likely to increase.

Also, they are moving slower. This is called "translation speed." A storm like Harvey in 2017 didn't just hit Texas; it sat there. It crawled. Because it stayed in one place, it dumped trillions of gallons of water. Whether you call it a hurricane or a cyclone, a stalled storm is a catastrophe.

Essential Preparation Steps

Understanding the terminology is the first step toward safety. If a meteorologist says a "tropical cyclone is forming," don't wait for the word "hurricane" to start moving.

- Know your zone: Check local government maps to see if you are in an evacuation zone. This is usually based on storm surge, not wind.

- The 3-Day Rule is dead: Most experts now recommend having at least 7 days of supplies. Power grids in major storms can take weeks to repair.

- Water is the killer: Roughly 90% of deaths in tropical cyclones are caused by water (surge and inland flooding), not wind. If you are told to evacuate because of water, go. You can hide from wind, but you cannot hide from water.

- Seal the envelope: The most important thing for your house is keeping the wind out. Once wind gets inside through a broken window or a failed garage door, the pressure can actually lift the roof off from the inside.

Investing in impact-resistant windows or even just plywood shutters makes a massive difference. Don't rely on "tape on the windows." That is a myth and does absolutely nothing to stop a breach.

Always monitor the National Hurricane Center (NHC) or the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) depending on your hemisphere. These agencies provide the "cone of uncertainty," which shows where the center of the storm might go. Remember, the storm is always much wider than the cone.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Download the FEMA app or your local emergency management equivalent to receive real-time alerts.

- Locate your main water shut-off valve and electrical panel; you may need to turn these off if flooding is imminent to prevent fires or contaminated pipes.

- Audit your "Go Bag" tonight—ensure it contains physical copies of insurance documents and at least $200 in small bills, as ATMs and credit card machines fail when the power goes out.