Opposites attract. It sounds like a cliché from a bad romance novel, but in the world of subatomic particles, it's the law. If you’re looking for a formal ionic bond definition, you’ll usually find something about the complete transfer of valence electrons between atoms. But honestly? That’s a bit of a lie. Or at least, it’s a massive oversimplification that high school textbooks use because the reality is much messier.

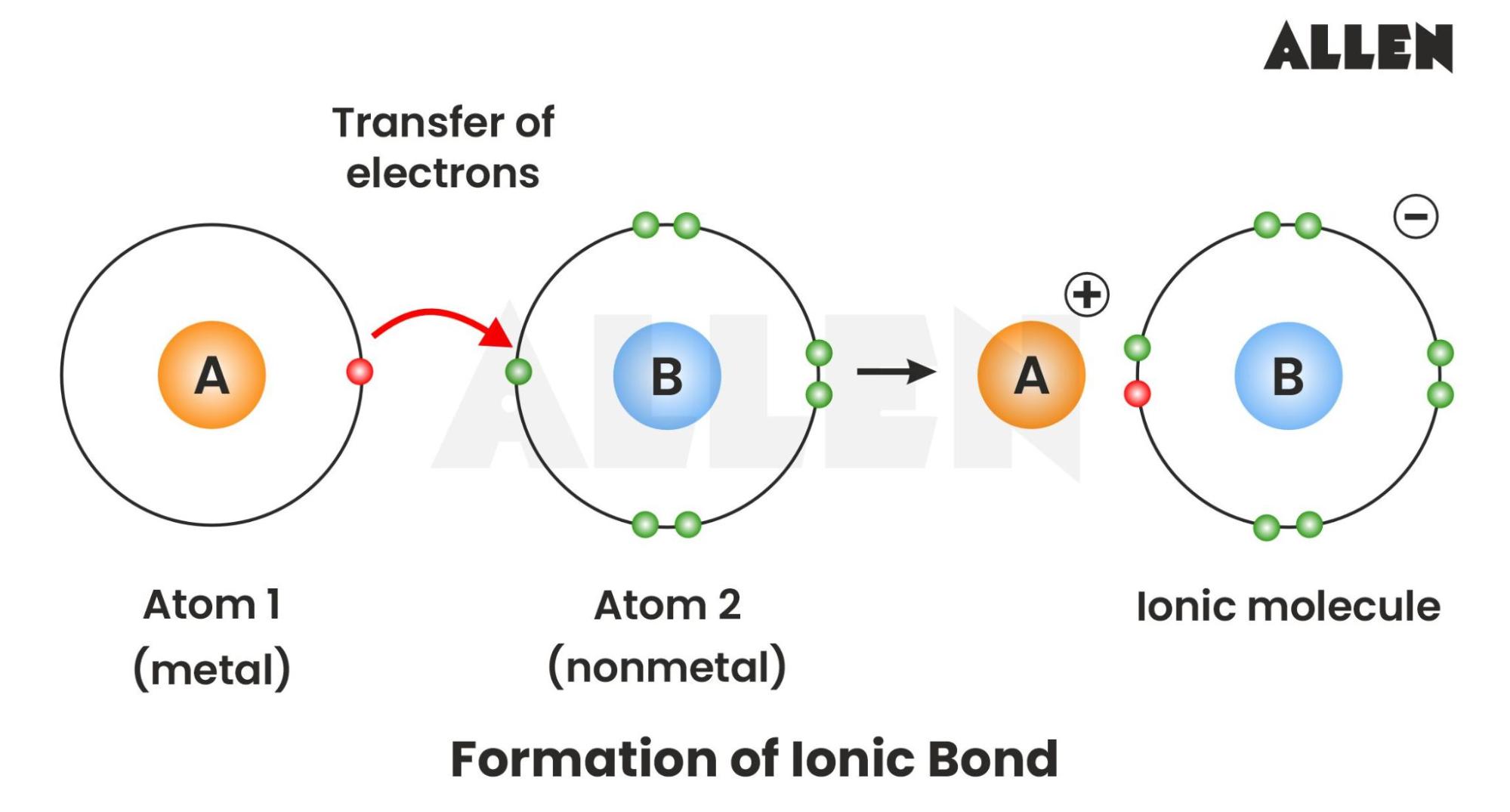

Chemistry isn't just about atoms wanting to be "happy" with a full shell of electrons. Atoms don't have feelings. They have energy states. An ionic bond happens when one atom is so much more "greedy" for electrons—what we call electronegativity—that it effectively yanks an electron away from a weaker neighbor. This creates ions. One is positive, one is negative. They stick together like powerful magnets.

The tug-of-war you didn't know was happening

Think of a chemical bond like a tug-of-war. In a covalent bond, the two atoms are evenly matched, so they share the rope. In an ionic bond, one side is a professional powerlifter and the other is a toddler. The powerlifter takes the rope and walks home.

This dramatic transfer usually happens between a metal and a non-metal. Take table salt (Sodium Chloride). Sodium has one lonely electron in its outer shell. It’s loosely held, almost like it’s waiting for an excuse to leave. Chlorine, on the other hand, is one electron short of a "perfect" set. When they meet, the electron doesn't just drift; it’s captured.

Now, sodium has more protons than electrons, giving it a positive charge ($Na^{+}$). Chlorine has an extra electron, making it negative ($Cl^{-}$). They are now ions. Because they have opposite charges, the electrostatic force pulls them together. That force? That's the bond.

Understanding the ionic bond definition in the real world

We often talk about "an" ionic bond as if it’s a single pair of atoms. It’s not. If you hold a grain of salt, you aren't holding two atoms stuck together. You’re holding a massive, repeating jungle gym of millions of ions. This is called a crystal lattice.

Each positive sodium ion is surrounded by six negative chlorine ions, and vice versa. There is no "individual" molecule of $NaCl$. It’s just a giant, organized crowd. This is why ionic compounds behave so differently from things like water or oxygen.

- They have incredibly high melting points. You have to get salt to about 801°C (1,474°F) just to turn it into a liquid. That’s because the electrostatic attraction is so strong throughout the whole lattice that you need massive energy to break them apart.

- They are brittle. If you hit a salt crystal with a hammer, it shatters. Why? Because you’ve shifted the layers of atoms. Suddenly, positive ions are sitting right next to other positive ions. They repel each other instantly. The crystal literally blows itself apart at the point of impact.

Electronegativity is the secret sauce

How do we know if a bond will be ionic? We use the Pauling scale, named after the legendary chemist Linus Pauling. He developed a way to measure how badly an atom wants an electron.

If the difference in electronegativity between two atoms is greater than about 1.7, we call it ionic. If it’s lower, it’s covalent. But here is the secret: nothing is 100% ionic. Even in the strongest ionic bonds, there is a tiny bit of electron sharing happening. It’s a spectrum, not a binary.

- Fluorine is the most electronegative element (4.0).

- Francium is the least (0.7).

- A bond between these two is as "ionic" as it gets.

Most of what we interact with lives in the gray area. But for the sake of simplicity, the ionic bond definition remains our go-to way to describe the extreme "theft" of electrons that builds the solid world around us.

Why does this actually matter?

Without ionic bonding, your body would stop working in seconds. Your nervous system uses "ion channels" to send signals. When you decide to move your finger, your body moves sodium and potassium ions across cell membranes. This creates an electrical impulse.

It’s also why salt dissolves in water. Water molecules are "polar," meaning they have a slight charge. They crowd around the salt crystal and pull the ions away one by one, surrounding them like a protective huddle. If salt were held together by covalent bonds, it wouldn't dissolve the same way, and our blood chemistry would be impossible.

Common misconceptions about ionics

People often think ionic bonds are the "strongest" bonds. It's a "yes and no" situation. In a vacuum, or within a solid crystal, they are incredibly tough. But put them in water? They fall apart instantly. Covalent bonds, like those in a diamond or even a simple sugar molecule, don't just disintegrate in water.

Also, don't fall into the trap of thinking metals only form ionic bonds. Metals can bond with other metals (metallic bonding) where electrons flow like a sea. The ionic "theft" only happens when there is a massive power imbalance between a metal and a non-metal.

Actionable insights for students and hobbyists

If you are trying to master this concept for a lab or an exam, stop trying to memorize the periodic table and start looking at the groups.

- Group 1 and 2 (Alkali and Alkaline Earth metals) are your primary electron givers. They are the "weak" ones in the tug-of-war.

- Group 16 and 17 (Halogens and Oxygen group) are your electron takers.

- Check the solubility. If a substance dissolves in water and the resulting liquid conducts electricity, you're almost certainly dealing with an ionic compound. This is because the free-floating ions act as tiny wires to carry the current.

To really grasp the ionic bond definition, try visualizing the energy. Atoms aren't trying to be happy; they are trying to reach the lowest energy state possible. For a metal, losing that pesky outer electron is the easiest path to stability. For a non-metal, grabbing one is the shortcut. The bond is just the byproduct of that search for rest.

Next time you shake some salt onto your fries, remember you're eating a controlled electrical explosion. The sodium was a metal that explodes in water, and the chlorine was a toxic gas. Together? They’re just a stable, square-shaped crystal that makes your food taste better. That is the power of the ionic bond.

📖 Related: Buying a TV LED Smart 4K? Here is What Salespeople Won't Tell You

To deepen your understanding, look up the "Born-Haber cycle." It's the mathematical way chemists calculate exactly how much energy is released when these bonds form. It proves that the "theft" isn't just a random act; it’s a calculated move by the universe to settle into a more stable state.