Ever wonder why salt doesn't just evaporate when you leave it on the counter, but a puddle of water disappears in a day? It’s basically all down to the way atoms hold onto each other. If you're looking for a solid ionic bond definition chemistry buffs can actually use, you’ve gotta look past the simple "stealing electrons" analogy. It’s more like a high-stakes magnetic attraction born out of a total identity shift.

Chemistry is often taught as a series of rigid rules. But honestly? It’s chaotic. At its heart, an ionic bond is a type of chemical linkage formed from the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions in a chemical compound.

The Identity Crisis of Atoms

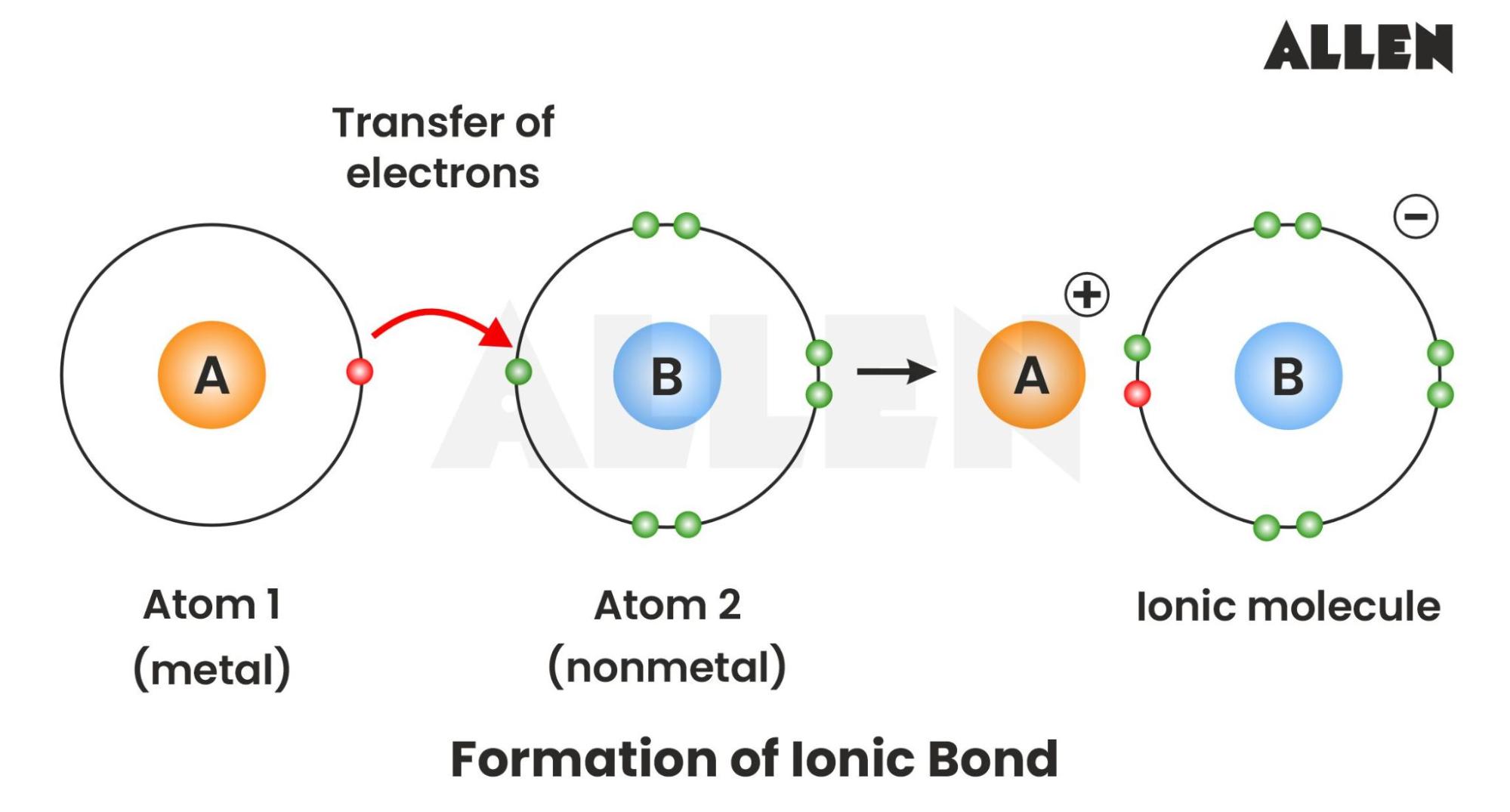

Atoms want to be stable. Most of them are pretty "unhappy" in their natural state because their outer electron shells are incomplete. To fix this, they either share electrons (covalent) or they just go for a total transfer. This transfer is what creates the ionic bond. Imagine a sodium atom. It’s got one lonely electron in its outer shell. It wants to get rid of it. Chlorine, on the other hand, is one electron short of a full set.

When they meet, sodium gives that electron to chlorine.

👉 See also: Apple Store in North Star Mall: What Most People Get Wrong Before Visiting

Now, sodium has a positive charge ($Na^{+}$) because it lost a negative electron. Chlorine becomes negative ($Cl^{-}$) because it gained one. Because opposites attract, they stick together like super-strong magnets. That's the ionic bond definition chemistry students usually memorize for the midterm, but the "sticking" is where the magic happens.

Why We Call It "Electrostatic"

You'll hear the word "electrostatic" tossed around a lot. Don't let it freak you out. It just means the force between two stationary charges. In an ionic bond, this force is incredibly powerful. It’s way stronger than the forces holding together a molecule of sugar or water.

This strength is why table salt has a melting point of about 1,474°F (801°C). You can’t just melt it on your stovetop. You’d need an industrial furnace. This massive energy requirement is a direct result of the ionic lattice structure. Instead of forming discrete little "pairs," these ions stack themselves into a giant, repeating 3D grid.

The Lattice: It’s Not Just One-on-One

One huge misconception is that an ionic bond is just one sodium atom stuck to one chlorine atom. It isn't.

When you look at a grain of salt, you’re looking at millions of ions organized in a cubic crystal lattice. Every single positive sodium ion is surrounded by six negative chlorine ions, and vice-versa. They are all pulling on each other at once. This isn't a "molecule" in the traditional sense; it’s a formula unit. If you tried to point to one specific sodium and say, "That's chlorine's partner," you'd be wrong. It’s a community effort.

Predicting the Bond: Electronegativity Matters

How do we know if two atoms will actually form an ionic bond instead of just sharing? We look at Pauling’s electronegativity scale. Linus Pauling, a giant in the field, figured out that if the difference in "greediness" for electrons between two atoms is greater than 1.7, the bond is usually considered ionic.

If the difference is small, they share. If it's huge, one atom basically mugs the other for its electron.

Real-World Heavy Hitters

Ionic bonds aren't just for salt. They are everywhere.

- Calcium Chloride: That stuff people throw on icy sidewalks. It’s ionic. It works better than salt because it releases more heat when it dissolves.

- Magnesium Oxide: Used in furnace linings because its ionic bonds are so tough they can withstand extreme heat without breaking down.

- Lithium Bromide: Used in industrial air conditioning systems.

When Ionic Bonds Break (The "Dissolving" Trick)

Put salt in water and it disappears. Did the bonds break? Yes and no. Water is a "polar" molecule, meaning it has a slight charge. The water molecules crowd around the ions and pull them out of their lattice. This is called hydration.

The bond isn't "gone" in a permanent chemical sense—if you evaporate the water, the ions find each other again and snap back into that lattice. This ability to conduct electricity when dissolved is a hallmark of ionic compounds. We call these electrolytes. Your heart literally wouldn't beat without the movement of these ions across your cell membranes.

The Limitations of the Definition

Is any bond 100% ionic? Probably not. Even in something like Cesium Fluoride ($CsF$), which is often cited as the "most" ionic compound, there’s a tiny, tiny bit of electron sharing happening. Chemistry likes categories, but nature likes gradients. Most bonds exist on a spectrum between purely covalent and purely ionic.

Hard, Brittle, and Stubborn

If you hit a piece of metal with a hammer, it dents. If you hit a large salt crystal with a hammer, it shatters. Why?

When you strike an ionic crystal, you shift the layers of ions. For a split second, positive ions line up with other positive ions. Since like charges repel, the crystal literally pushes itself apart. It’s a violent, microscopic rejection that results in a clean break.

How to Identify an Ionic Compound Instantly

If you’re looking at a chemical formula and trying to decide if it fits the ionic bond definition chemistry standard, check the Periodic Table.

- Is there a metal (from the left side)?

- Is there a non-metal (from the right side)?

- If yes to both, it’s almost certainly ionic.

Metals have low ionization energy; they give up electrons easily. Non-metals have high electron affinity; they crave them. It's a match made in... well, in the electron shells.

Summary of Key Properties

Ionic compounds usually share these traits:

✨ Don't miss: Making Pixel Art with Photoshop: What Most People Get Wrong About the Setup

- High melting and boiling points.

- Solid and crystalline at room temperature.

- Insulators when solid, but great conductors when melted or dissolved.

- Usually soluble in water.

Actionable Next Steps for Mastery

To really get a handle on how these bonds function in a practical lab or academic setting, stop just reading and start predicting.

- Check the Electronegativity: Grab a periodic table that includes electronegativity values. Subtract the smaller number from the larger one for a pair like $K$ and $Cl$. If it's above 1.7, you've confirmed an ionic bond.

- Visualize the Lattice: Look up "Unit Cell" structures. Understanding the difference between Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) and Body-Centered Cubic (BCC) will help you see why different ionic solids have different physical strengths.

- Conduct a Conductivity Test: If you have a basic circuit and a multimeter, test the resistance of distilled water versus salt water. The drop in resistance is the direct result of ionic bonds breaking and ions becoming mobile charge carriers.

The world is held together by these invisible tugs-of-war. Understanding the ionic bond definition chemistry provides isn't just about passing a test; it's about understanding why the ground under your feet is solid and why the ocean is salty. It’s the foundational physics of our physical reality.